AAP Needs To Determine What It Stands For Beyond Corruption

NEW DELHI: One would normally expect a fledgling political party up against not one but two established and considerably better-resourced rivals to happily settle for a 24% vote share and second position in the final seat tally.

But it is a measure of the Aam Aadmi Party’s (AAP) ambition and pre-poll confidence that it finds itself disappointed after the recently concluded Punjab assembly election results where it has achieved precisely that. After all, the party was banking on a Punjab win to give momentum to its pan-India plans and dispel the notion of it being a force only in Delhi.

The AAP setback in Punjab may have had to do with a host of local factors, including a weak organization, lack of a chief ministerial face and, if some reports are to be believed, a joint Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-Congress conspiracy, and those issues will probably be addressed in time but there is another larger issue for the AAP to reflect on going forward.

It may not have come to the fore in Punjab where the party made its earliest inroads after Delhi but will bear on whether the AAP is able to make intended impact in other states and on the national political scene.(Unlike other non-BJP, non-Congress parties, the AAP isn’t content with the state/ regional tag and a large part of its attraction is that pits itself against the country’s two largest parties and aspires to blunt them.)

Before delving into the key ponderable for the AAP, it is important to appreciate what it has achieved so far and how popular perceptions about it are evolving.

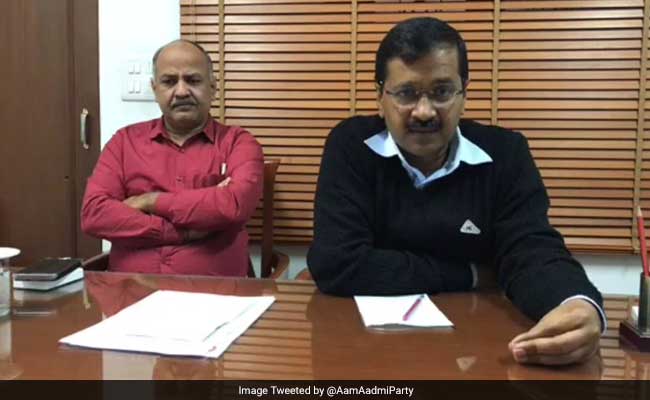

It is difficult to contest that Arvind Kejriwal and his party have made their presence felt on the national political stage within a short span of time with little financial backing or organizational muscle. (Arguably, the last politician before Kejriwal to have captured nationwide attention amidst similar constraints was V P Singh in the late 1980s.)

Further, notwithstanding fall-outs with erstwhile close comrades such as Prashant Bhushan and Yogendra Yadav and all sorts of allegations against partymen in Delhi and Punjab, Kejriwal’s clean, crusading image remains intact and has drawn a small but fiercely loyal and energetic band of supporters.

Having said that, it is difficult to shake off the feeling – and this is a feeling that emerged before Punjab went to the polls - that the AAP’s growth has begun plateauing. Ironically, this could be on account of the same strategies that have served it well so far.

Much of Kejriwal and the AAP’s current profile owes to sharp anti-establishment positions on the issues of the day, systematic targeting of top BJP and Congress leaders and exposes against rival parties and their corporate cronies. Television’s preference for the sensational has provided the much-needed amplification to the messaging.

All this carried great resonance at a time when public anger against the Manmohan Singh-led government at the center and the Sheila Dixit-led government in Delhi was at its peak. However, with the advent of Narendra Modi at the center and Kejriwal’s own assumption of Delhi’s chief ministership, dividends from the same tactics appear to be diminishing.

With PM Modi in a different league from former PM Manmohan Singh and the Gandhis in the popularity stakes, the BJP’s communication and counter-communication machinery in good shape and Kejriwal’s own crossover to the establishment side, the AAP’s trenchancy has suddenly started sounding a trifle hollow and forced, even theatrical.

Ennui has set in, with a section of opinion viewing the AAP’s utterances as prompted more by habitual attention-seeking than substance. This is not to suggest that the AAP’s stances against the Modi sarkar lack merit but to underline that they haven’t quite connected as before.

Bluntly put, Kejriwal and the AAP runs the risk of frittering hard-earned goodwill and credibility unless there is serious introspection on – and explicit articulation of - what the AAP stands for (going beyond what it doesn’t stand for).

Of course, the AAP has spoken about eradicating corruption, serving the poor, punishing crony capitalism, protecting the environment, upholding national security, etc,., from time to time but these are unexceptionable aims that hardly position the party differently from any other.

On more polarizing matters such as caste-based reservations or the rights and privileges of religious minorities, little is known about the AAP’s position. Such overall lack of positioning can be potentially fatal for a party that has fired cadres with the promise of a new type of politics.

To be accurate, some idea of what the AAP stands for does come from the stances it has taken on various issues but these stances - generally post-event/ retrospective and not located within a larger, coherent and clearly spelt framework and worldview - have only opened the gates for allegations about political opportunism.

And given credence to those inclined to label the AAP as a bunch of perpetually naysaying drama queens. One can’t help but think that the AAP’s views on water sharing with neighboring Haryana or center-state relations in general would have carried more weight had they been rooted in a larger, pre-argued frame.

Is it unfair to expect a fledgling party to evolve coherent stands on pressing contemporary issues when every other political party in the country, including the Grand Old Congress, struggles to do the same?

Perhaps, but AAP supporters will draw confidence from the disruption their young, under-resourced party has achieved in Indian polity as they proceed with the endeavor.

(Manish Dubey is a policy analyst and crime writer with an interest in politics, cinema and cricket.)