Hate Crimes Are Against All Humanity

SHOMA A.CHATTERJI

Is it not possible to place the hate crimes and killings of members of a given minority or caste as killings against humanity? Why cannot, we as a collective body of people, widen the horizons of our perspective and view every hate crime as a crime against humanity? Why can’t we rise above the partisan approach of tagging every crime with a caste or a religious or a gender label? Isn’t the victim a human first and then the member of a given caste or community?

These questions were raised through an article in a Bengali daily (Ananda Bazar Patrika, July 2, 2017) under the title, “Should we look at the faith of the person attacked?” Ansuman Kar, the author, appeals to us to take a more neutral and objective world-view of these hate crimes and killings by rising above the religious faith or given caste or gender of the victim.

The term ‘hate crime’ was coined in 1985 in legislation centered on the US Justice Department’s collection of “hate crime statistics”, according to James B. Jacobs and Kimberley Potter in their book Hate Crimes: Criminal Law and Identity Politics. In the American Psychological Association’s 2003 report entitled Hate Crimes Today: An Age-Old Foe in Modern Dress, criminologist Dr. Jack McDevitt states: “Hate crimes are message crimes. They are different from other crimes in that the offender is sending a message to members of a certain group that they are unwelcome.”

West’s Encyclopedia of American Law defines a hate crime as “a crime motivated by racial, religious, gender, sexual-orientation, or other prejudice.” But the term does not always carry a definite meaning. It changes from person to person, from time to time and from place to place. Eve Gerber in Slate writes: “The definition of hate crime varies.” She goes on to argue her theory by pointing out how it differs within the US from one state to another. While 21 states in the US include mental and physical disability, 22 include sexual orientation, and three states including the state of Columbia impose tougher penalties for crimes based on political affiliation.

The Federal Bureau of Investigations (USA) defines a hate crime as a “criminal offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender or gender identity.” A sweeping glance across the map of contemporary world history however, will beg the question. What difference do different meanings attached to hate crimes really make to the victims of the Gujarat genocide? Do any definitions matter to the Sri Lankan Tamils, or to the women in Manipur, or to the common man, woman and child in terror-stricken J & K?

Never before September 11, 2001, was man made to realise that ‘hate’ and ‘fear’ are four-letter words that can change the history of mankind forever through a strange kind of institutionalisation of terrorism. From Bali in Indonesia to Najaf in Iraq, to Gujarat in India and Jaffna in Sri Lanka, hundreds of civilians have been killed in acts of politically motivated violence.

The bombing of the United Nations office in Baghdad, killing more than twenty people, marked a new low in the history of attacks against humanitarian workers. In Israel and the Occupied Territories, Palestinian armed groups have killed scores of civilians in repeated suicide bombings.

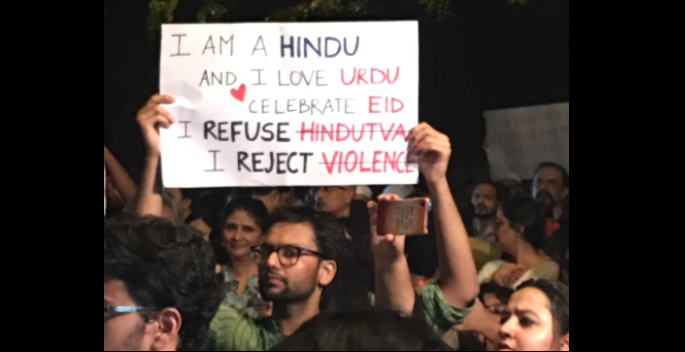

Every public outcry, ever candle-light procession, every “NOT IN MY NAME” rebellion is heavily underlined by the adjective of the victim be it a raped woman like Nirbhaya, or 15-year-old Junaid who was Muslim. This ‘boxing’ of the victim by attaching to his identity a religious, gender or casteist tag somehow dilutes the importance of the fact that the victim is/was a human being first and a woman or a Muslim or a Dalit afterwards. It is as if we are unwittingly denying the multi-faceted layers of the victim’s identity. We all live and work in a society where we are masons or librarians or professors. We also are daughters, husbands, sons and brothers.

We may be illiterate, educated, skilled or unskilled, rich or middle-class or poor. Gender, the religious faith or the caste we are born into or have converted to is just one among these. We are a cohesive whole, made up of all these different personas. Then why must just one, now very sensitive segment of these different layers be ‘boxed’ exclusively by a protesting public when an innocent victim is killed or lynched or stabbed to death? Is he not is a human being first and then a Muslim?

This “They/We” dilemma hardly dissolves with this labelling of hate crimes with appendages like ‘gender’. ‘caste’ and ‘religion.’ The response to these people protests, are, at best, temporary salves followed by a lot of media hype that might make the PM voice his anger, very politically keeping away from mentioning a single name of the victims of such mindless assault. But there it all ends. The television news channels make hay while the lynchings and rapes and murders go on, almost pouncing on the sensationalism quotient of these tragedies.

Kar quotes from noted Muslim-American poet Kazim Ali’s The Disappearance of Faith. The book unfolds the interlocking stories of five New Yorkers, stumbling through their lives in the aftermath of September 11 connected by the paths of two characters—Seth, an alienated young man struggling to come to terms with his own penchant for violence, and Layla Fuyad, an Iraqi artist who fled the violence of the first Gulf War and made a new home for herself in New York City.

Layla saves Seth’s life during an attack on him by a few white-skinned Americans who mistake him for an Arab-Muslim. Some time later, Seth tells Layla that she has actually harmed Seth by saving him because had she not interfered, he would have attacked them right back in revenge. Layla tells him that she would have saved anyone from such attack because for her, to save an attacked human being was the most important thing. If she had not saved him, that would have been an act of violence. Had he retaliated with violence, she would have rushed to save those Americans too.

For Layla, the most important thing of an attacked person is that he the victim of an attack, per se and therefore, it was the responsibility of every fellow human to stand beside him and try to save him from being attacked. The Disappearance of Seth features both Muslim and non-Muslim, American and non-American in a forthrightly critical and analytical portrait of life in America at the beginning of the millennium.

Granted that when an innocent person is attacked by another person or group the common man and woman will automatically focus on the ‘why’, ‘when’ and ‘by who’ he was attacked rather than accept the basic reality that he was attacked. Is that not enough to rise and retort in anger? Someone has said, “The naked has no identity but that he is a human being. Put clothes on him and he might quite as easily become a killer, or a victim, or both.” Take away the skull cap and we identify him as the boy next door. Is it necessary to box the victims and their attackers in labelled coffins that will harm the cause more than benefit it?