'When Breaking the Law is Sometimes the Only Way to Live Up To The Demands of a Higher Law'

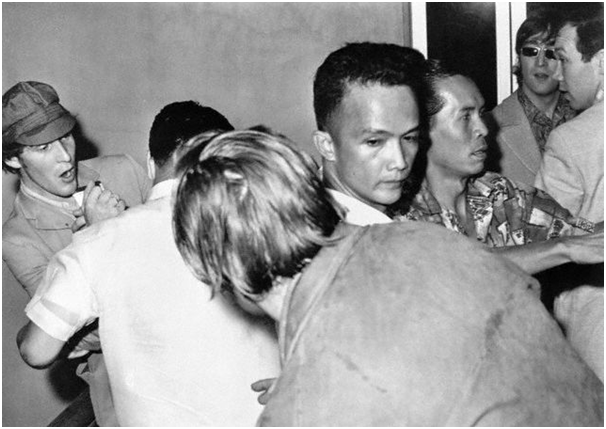

The Beatles snubbed Dictator Marcos who set the mobs on them in Manila. July 6 1966

September 21, 2015 being the 43rd anniversary of the declaration of martial law, I would like to share three tales from the anti-Marcos resistance abroad that illustrate why breaking the law is sometimes the only way to live up to the demands of a higher law.

It was 1975, and I had just finished my PhD at Princeton. At that time, an academic career was something that I had no intention of pursuing. The task at that time was quite clear to me: to overthrow the Marcos dictatorship. I became part of an international network connected to the Philippine underground and a full-time activist. I went to Washington and helped set up an office that lobbied the US Congress to cut aid to the Marcos regime.

Soon we realized that in order to do any effective work, we had to look at all the dimensions of US support for the dictatorship. For example, the largest part of US aid to Marcos was channeled through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, and the problem was that the lack of transparency of the Bank meant that we couldn’t get any information about the Bank programs. The only information that we got came from sanitized press releases. It became clear that to show what the Bank was doing and expose it, we had to get the documents from within the Bank itself. At first, we slowly formed a network of informants within the Bank. These were acquaintances, "liberals with a conscience." Our work was part of a process of building what was effectively a counter-intelligence network not only within the Bank but also within the State Department and other agencies of the US government.

Well, these people started to occasionally bring us some documents, but this was a tedious – although necessary – process. The information was not enough, so we thought that it was necessary to resort to more radical means.

So, my associates and I investigated the patterns of behavior of Bank people, and we realized that there were sometimes in the year when there was nobody in the Bank: Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s Day, July 4, Memorial Day, etc. On those days and over a period of three years, we went to the Bank pretending that we were returning from a mission, with our ties askew and said that we were just coming from Africa, India, etc. The security guards always asked for our IDs. When we pretended to fumble for them, since we looked so tired, they said, ‘OK, just go inside.’ It always worked. As you can imagine, security was quite lax in those days.

Once we were inside, we were like kids let loose in a candy store. We took as many documents as we could – and not just reports on the Philippines – and photocopied them using the Bank facilities. This happened over three years!

The documents – some 3,000 pages of them on practically every Bank-supported project and program in the Philippines – provided an unparalleled look at the workings of a close relationship between two non-transparent authoritarian institutions, the World Bank and the Marcos regime. First, we held press conferences to expose the documents piece by piece, to the embarrassment of both the Bank and the Marcos regime. Eventually, we came out with a book, published in 1982 by Food First, entitled Development Debacle: The World Bank in the Philippines. According to many people, this book contributed to the unraveling of the Marcos regime. I hope they were right.

As for what I learned, well, it was that accepted or orthodox methods have their limitations and that to do really effective research sometimes you need to break the law. But you have to be utterly professional in the process. We were quite careful in going about it, and we were not able to tell the real story about how we got the documents until 10 years later (1992), when the statute of limitations for criminal prosecution in the US had lapsed. My associates and I could have gotten 25 years in jail had we been caught breaking into the Bank, though of course good behavior would have shortened that jail stint with an early parole.

But on a more serious note, the decision we had to make was not easy. It is never easy to decide to break the law, not only because of the penalties involved but because we all are so deeply socialized to follow the law. But we felt that we had no choice. Otherwise, the truth would have been buried for a long, long time, in the vaults of the World Bank.

How opposing Marcos got me addicted to burritos

In 1978, the dictator Marcos held one of his stage-managed elections.

To draw international attention to this vile maneuver, several of us took over the Philippine Consulate in San Francisco. We threw out the staff, including the consul general, and locked ourselves in.

A standoff of a few hours took place, as the police tried to convince us "terrorists" to give up. When we refused to do so, the SWAT team broke down the doors, fired tear gas at us, and through the application of force at strategic points of the body (e.g., placing the baton on one's throat and pulling it up), they succeeded in breaking up our human chain and put all of us under arrest.

At our trial a few weeks later, the judge offered us a lenient sentence after finding us "guilty" of a whole host of crimes, including trespassing, destruction of property, and resisting arrest. We refused the judge's offer, calling him Marcos' stooge, and told him we did not recognize the authority of the court and proceeded to walk out. At that point, the court marshals tackled us and hauled us off to the San Francisco County Jail in San Bruno, California, where we were told we would have to serve out a month-long sentence among hardened criminals.

After one week we decided we had to find a way to break out of the jail. So we staged a hunger strike, telling the press we would do it till we died. During the next week, we ate nothing. Not only did the other inmates not harm any of us. They donated their supplies of orange juice to us and started to chant the anti-Marcos slogans that we taught them.

As I weakened, all that I could think of all day was a supersize carnitas burrito.

Fearing that we would in fact fast unto death and worried about the example of civil disobedience we were providing to the regular inmates, some of who were, in fact, thinking of joining our fast, the warden ordered us released after a few more days.

Upon release, I rushed to my favorite Mexican fast-food place on 16th and Mission in San Francisco, and downed the supersize carnitas burrito I had been dreaming about for over a week.

Not surprisingly, I got horribly sick from such instant gratification and spent the next week outside prison in a worse state than when I was in jail. Every time I went to the toilet, I grunted "Down with Marcos" with all my intestinal might, and that was the secret of my recovery.

Imelda, Van Cliburn, and pandemonium at Kennedy Center

It must have been 1980, during the depths of martial law, when news about the resistance to Marcos in the Philippines was so hard to get out to the international mainstream media.

Imelda's coming to Washington, however, offered an opportunity. The event was Cecile Licad's concert at the Kennedy Center, which was attended by Imelda and her good friend, the renowned pianist Van Cliburn. Activists in the Anti-Martial Law Coalition in Washington, DC, decided to give the dictator's wife the surprise of her life: we planned to disrupt the concert.

Now, one disrupts political events, but never, never an exclusive event where the rich and the famous get together to connect with high-brow culture to have their souls washed and lifted by the music of Beethoven, Bach, and Brahms. But we uncivilized bastards were desperate. Nothing was going to stop us from spoiling the dictator's wife's evening and showing Washington and the world that the Philippine resistance was alive and kicking.

A number of us paid a fortune – some $75 a ticket – to get into the damned event, and I borrowed a friend's tweed blazer to look respectable. We waited till the end of the first piece, something from Tchaikovsky or some other mad Russian, before making our move.

At a given signal, I cried, "There's a fascist in the house," and pointed to the box in the balcony where Imelda was sitting, pretending to appreciate the music, along with Van Cliburn, probably holding hands, though I couldn't tell for sure. A number of us rushed to the front and unfolded a banner that read "Down with the US-Marcos Dictatorship!"

At that point, pandemonium broke loose, with some people thinking someone shouted fire. The Washington, DC, police was called in, and over the next 20 minutes, they went after us as we ran between the rows of seats, jumping over people, with people screaming and shrieking. Finally, the last one of us was nailed down, wrested to the floor, handcuffed, arrested, and marched off to the police station.

The concert resumed, but Imelda's evening was spoiled. Unfortunately, Cecile Licad also lost her poise, but I guess that's what she got for allowing herself to be patronized by Imelda. As for Van Cliburn, I guess he probably began to realize he had to stop holding hands with Imelda or risk his reputation.

At the police station, we were told that the Kennedy Center management decided not to press charges, and when we told the police we were protesting Imelda's presence, they said, "Marcos' wife?" They laughed and let us go, showing that even among some policemen there were anti-fascist sentiments, at least when it came to Marcos.

The next day, a piece in the Washington Post carried the headline "Protesters Disrupt Kennedy Center Concert." Great. Barbarians 1, Marcos 0.

Anyway, for me, it was also a way to avenge the Beatles, who were nearly beaten up by Imelda's hordes when they snubbed a reception she gave when they visited Manila back in 1966. The Beatles probably saw what the rest of us did not yet see at that point. What prescience! That's one of the things that made them a great rock band.