Repeating Falsehood and Making Stuff Up To Divert Attention from Social Woes

President Barack Obama’s recent commencement address at Rutgers University in New Jersey has raised some uncomfortable truths about public life.

In a wide-ranging critique of the 2016 presidential campaign, Obama warned against a culture of chauvinism and falsehood. He pointed out the dangers of wilful ignorance of leaders and commentators who insist on the supremacy of the past, and dismiss science and facts as elitist. He singled out the issue of inequality, and rebuked leaders for “repeating falsehood and just making stuff up” to divert attention from real social woes.

It is easy to say that Obama is a lame duck president, but this description ignores significant achievements in his second term. He has defied the powerful Israel lobby, and started reconciliation with Iran. He has overcome the lobby of Cuban exiles in the United States, and normalised relations with Havana. His visit to Vietnam and lifting of the American arms embargo has been hailed as opening a new chapter between the two countries. At home, Obama has nominated Merrick Garland to fill the Supreme Court position vacated by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia. A battle with his Republican opponents is expected in the Senate in the coming months.

Obama’s address at Rutgers University was primarily a commentary on the current state of affairs in America, but it could equally apply to Britain, India, indeed many other countries. Therefore, the theme of his address – in politics and in life, ignorance is not a virtue – is worth reflecting upon. For counter-factual and anti-intellectual tendencies anchored in cultural and religious chauvinism permeate many societies today.

Obama had Donald Trump in mind – the man with enough delegates to win the Republican Party’s presidential nomination for the November 2016 election, and who has made disparaging remarks about women, Hispanics, Muslims, almost every other minority, and foreigners.

If elected, Trump says he would build a wall at the US-Mexico border to stop immigrants, and force Mexico to pay for it. He would ban Muslims to stop terrorism. What would he do with the 55 million Hispanics and 3.5 million Muslims, the third largest religious community already in the United States? Obama’s comment was: “A wall won’t stop that.”

Donald Trump has become the most prominent icon for Americans who feel angry and bitter because of globalization resulting in a massive number of jobs moving abroad, and the presence of immigrants at home. But he is not the only one to harness the widespread discontent of mainly white working-class Americans for his political ends.

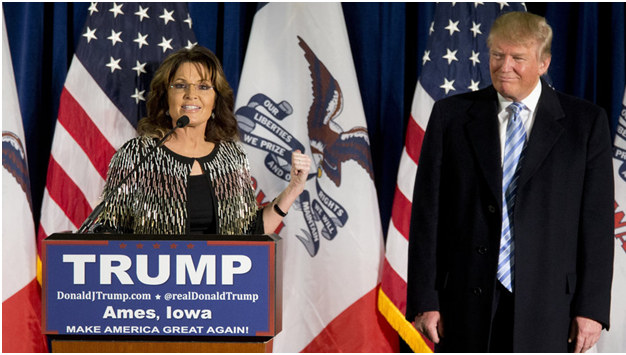

Ex-governor of Alaska and the 2008 Republican vice presidential candidate, Sarah Palin, another icon of America’s ultraconservatives, is known for making bizarre statements. She has endorsed Donald Trump, and in a jibe against Spanish-speaking people in the United States, she insisted that all “immigrants” will have to be legal, and will have to speak “American 24/7 – the way it’s been for thousands of years”.

For those who care about facts, colonisation of America by English settlers began in 1585, when Walter Raleigh sailed with about a hundred men to the east coast of the continent, and named the settlement Virginia. Before the English arrived, Spanish influence had been prevalent from the Chesapeake Bay to the tip of South America, including countries now known as Mexico, Peru and Cuba.

On the European side of the Atlantic, a fierce debate on immigration is taking place in Britain and across the continent. The debate presents disturbing aspects of raw human instincts – sectarianism, xenophobia, economic and class rivalries. Hyperbole and falsehood dominate the European debate. In a bitterly fought presidential election in Austria, the far-right Freedom Party candidate, Norbert Hofer, came within 0.3 per cent (31000 votes) of winning. Hofer’s manifesto was overtly anti-immigrant. Austria, once a Social Democratic bastion, is split down the middle, and the main parties fear that the far-right could win power in the 2019 general election.

Britain is in the midst of an acrimonious campaign before the upcoming referendum to decide whether the country should remain in the European Union, or leave. The issue has caused deep splits in the governing Conservative Party, and in the wider society. Supporters of remaining in the EU emphasise the balance of benefits, including the free movement of goods, services and people for British citizens, and many of the same rights they can enjoy throughout the 27 other countries of the European Union.

Those campaigning to leave have consistently been throwing up a figure of £350 million which they claim Britain pays every week for EU membership. In truth, Britain’s net contribution to the EU is less than half that. As the campaign has progressed, the focus of Leavers has shifted from the assertion of the British parliament’s absolute sovereignty to make all laws governing the country to immigration and firmer border controls.

The UK Statistics Authority, the official watchdog, first warned the Leavers against using the £350 million figure in their campaign literature, but the Leavers refused to heed the warning. So the official watchdog has advised the electorate not to trust the figure.

On the other hand, a parliamentary committee has accused both sides of misleading voters by exaggerating, embellishing, or inventing facts. The committee’s report says that a few grains of truth are buried under mountains of false claims which not only mislead the people, but impoverish the public debate.

Leading politicians on both sides appear overtly keen to demonstrate their mastery of history to support their argument. Some have not hesitated to invoke references to Hitler to claim, for example, that the EU’s agenda is to dominate Europe like Hitler. Others have asserted that if Britain leaves the association, the EU will be weakened and there will be another major war in Europe.

The tendency among leaders and commentators to insist on the supremacy of the past over science and facts is not only an American or European phenomenon. The drive in India, with official approval, to revert to religious scriptures thousands of years old to determine how people should live, and what children should be taught, is a case in point.

The inclusion of myths in science, and the rewriting of history, in pursuit of ideological goals is a slippery slope. When politicians at the highest level employ rhetorical questions like what did India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru achieve, or assertions such as the current government, having come to power just two years ago, has done more than its predecessors in sixty years since independence, the result is infectious, because many others follow.

Remember the Bhakra Nangal Dam Project (1948–1963); the Green Revolution (1960s); the India-Pakistan war that established India’s pre-eminence in South Asia (1971); and India’s first atomic test in the Rajasthan desert (1974)? Did those events mean nothing? Or were they important events which explain much about today’s India.

There are three main limitations of the postmodern world in the new century: crisis of leadership, fondness for instant answers, and supremacy of opinions over scientific methods and facts.

We should be careful, for when opinions are numerous, and the regard for facts scant, we live in an era of extremes.

(Deepak Tripathi is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. He lives near London.)