Bahujan Samaj in Goa Indica

“The oppressors do not favor promoting the community as a whole, but rather selected leaders.” Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed

The experience of being ruled by European power transformed British India and Portuguese Goa in considerably different ways primarily due to the character and practice of colonial administration of their metropolitan masters. During the eighteenth century, Britain was the leading European power at the pinnacle of its all-round development.

As against this, Portugal during its four and half century rule over Goa faced fluctuating fortunes from being a pioneer maritime power to underdog having conceded its naval superiority to Dutch and English.

As far as development of political thoughts and institutions are concerned, Portugal was way behind Britain as the Portuguese kingdom was in its infancy when Magna Carta the charter that established first time the principle that everybody including the king, was subject to the law was issued in England.

However, the more crucial difference in the two colonial administrative approaches was in the way and extent to which the two metropolitan powers engaged themselves with the local society while pursuing their economic interests.

No wonder, the development of a democratic process and institutions bear some distinct differences between the mainland (Rest of India) and the state of Goa. While British colonial practice was more need-based and practical, Portuguese attitude towards Goa changed from being evangelical in the beginning (old conquest area) to more focused on self-preservation and hence indifferent towards local society.

British Imperialism used India as a source of cheap raw material and market for finished goods to accelerate their industrial growth. In doing so, they destroyed traditional village economy which freed the lower caste villagers who deserted villages for urban centers and sought employment opportunities in newly emerging avenues such as bureaucracy, army, railways and industries in urban centers. To them, this was a liberating experience.

Education in English, equality before law and employment in the military provided a sense of identity and the first time the lower caste masses started questioning the rationale of the age old inequality and subjugation. This new awareness reflected in strident caste-based movements in the states of Maharashtra, Tamilnadu, and Punjab. British colonialists cleverly exploited these new caste identities for their divide and rule politics, but the emerging lower caste leadership was prepared to go along even at the cost of perpetuating British rule longer.

This equal access to colonial apparatus to all castes combined with a public discourse of rights and equality before the law had been the distinguishing factor between British colonial administration in India and Portuguese rule in Goa.

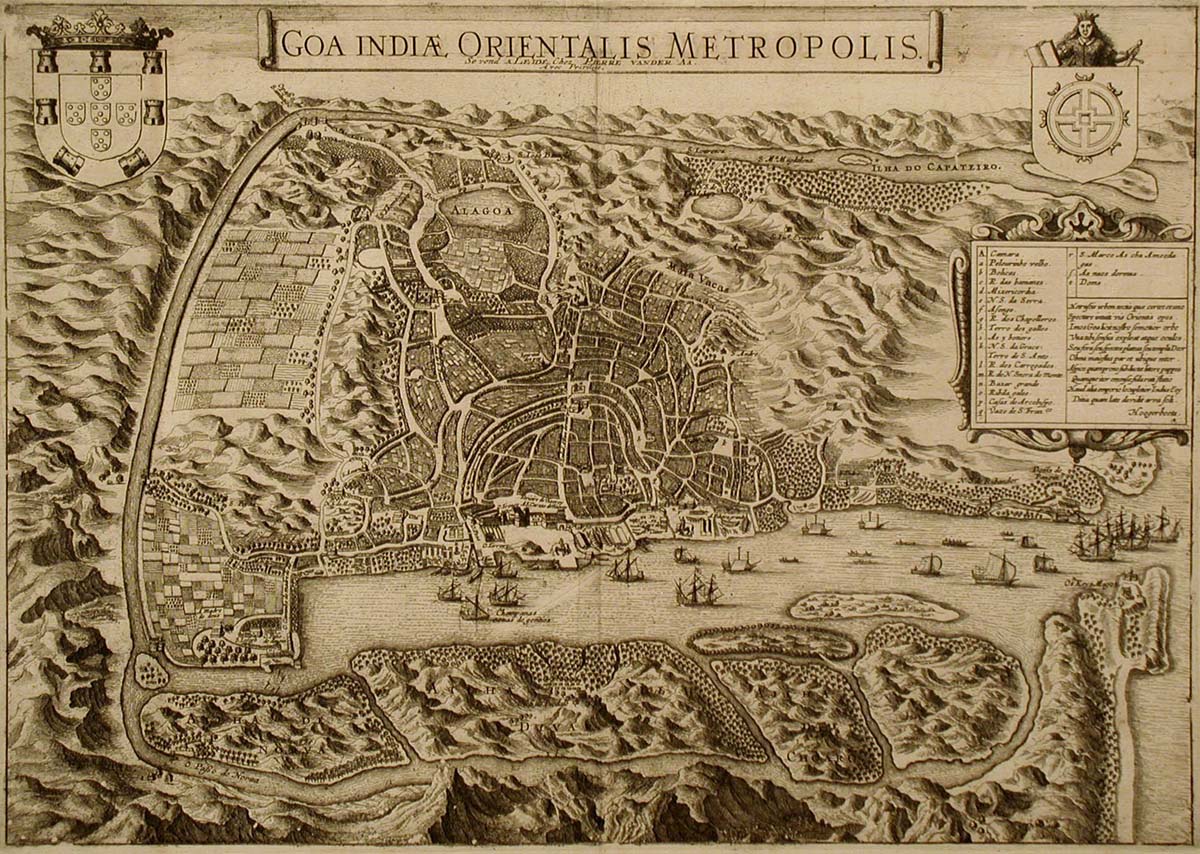

Goa may have been eulogized in many flattering ways as Rome of East, Goa Dourada or a lotus-eating island of the east. However, in a strictly economic sense, Portuguese administration used it as a trading outpost or toll post for sea lanes passing westwards through the Indian Ocean to control and realize the revenue by way of transit tax from the burgeoning east-west trade in spices and other precious goods.

The Portuguese proportioned their engagement with Goan society as per their core mercantile interests. They preferred to engage with the existing Gaud Saraswat Brahmin(GSB)elites who possessed sound scribal skills, commercial acumen, and business ready trading setups. Thus the Portuguese engagement with Goan society kept the caste hierarchy intact, and the local Portuguese administration seldom addressed the caste conflict issues except when it turned into law and order issue. The entire administration was mediated through upper caste GSBs many of whom had by then converted to Christianity.

Many times even Hindus upper caste were accommodated in the local ruling class. Slowly, the upper caste GSB Gentry called Bhatkars took control of important institutions like communidades, temples, and village panchayats. The large section of Bahujan Samaj consisting of Bhandaris, Gaudas, and Kharvis was not only excluded from power structure but had no access to colonial apparatus even if they adopted Christianity.

This exclusion of a vast majority of Bahujan Samaj engaged in farming and fishing continued to live under upper caste subjugation and lack of any identity. So much was the exclusion of Bahujan Samaj that the business of state administration right up to village Panchayat level was conducted in the Portuguese language known only to less than 2 % of the population which was mostly GSBs.

Further, the mercantilist colonial elite and their local counterparts had no motivation in the economic development of Goa by investing in agriculture which was backward or encouraging industrialization to produce essential goods and generate employment. In fact, the Portuguese were aware of Iron ore resources in Goa since seventeen century but did not tap it till as late as 1940 for fear of attracting greedy British interest!

In early twentieth century, the Goan industrial set up was limited to cashew nut processing, salt production, coir industry and liquor distillation. Most of the essential and luxury items were imported from British India with huge mark-ups that went into the pockets of GSB traders. Prominent Goan Nationalist Tristao Braganca Cunha while analyzing trade statistics observed that;

Between 1907 & 1936, while exports from Portuguese Goa has remained stagnant at around Rupees 24 lakhs, her imports have soared three times from 36.5 lakhs to around one crore.

The two societies emerging from such a different colonial experience responded quite differently in socio-economic and political sphere post-independence. But that will be a subject for some other time.