Appetite To Seek, Not Consume

A review of a new anthologyfrom Goa

“Appetite comes from ad and petere: to seek, to reach for, to beseech—not to consume.”

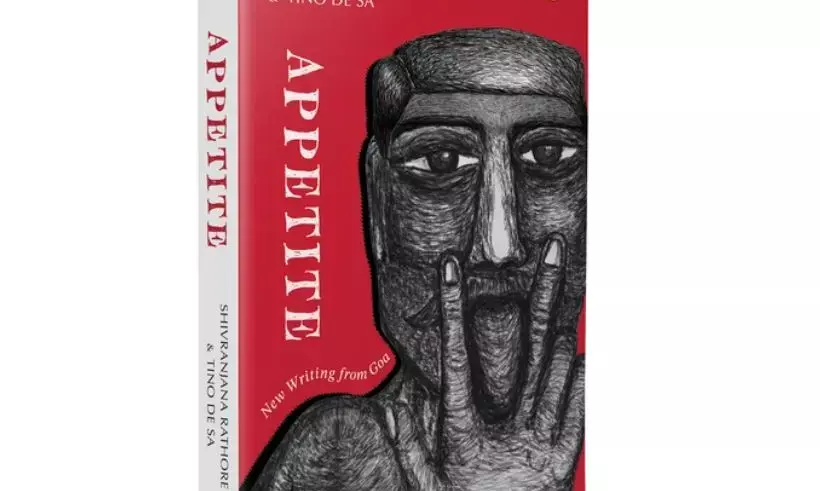

This etymological correction, offered midway through author Gail Pinto’s story Eucharist, does more than clarify a word. It provides the most precise frame for Appetite: New Writing from Goa (2026), edited by Shivranjana Rathore and Tino de Sa.

What does desire look like when it’s witnessed through multiple lenses? Consumed, torn apart, contextualized and reframed? In the Goa of today, appetite is perhaps a perfect word to describe the state’s socio-economic moment.

Amid intensifying debates in Goa around belonging, settlement, and entitlement, Appetite arrives, not as an anthology interested in indulgence, nostalgia, or easy consumption—of food, of place, or of Goa itself. Instead, it seeks. What it means to reach toward a place whose histories are layered, contested, and increasingly under pressure and what is longed for, denied, devoured, or left to rot in the process of becoming “Goa” in the present.

The anthology, published by Penguin, brings together fiction, poetry, and essays by members of The Goa Writers Group—a membership consisting of over 100 writers either based in Goa or Goan by ancestry, placed across India and the world— and its range is one of its strongest claims.

What emerges is not a single narrative of Goa, but a polyphony shaped by appetite in its many forms: hunger and excess, inheritance and erasure, desire and disgust, faith and doubt, survival and spectacle. The editors are explicit about resisting any claim to total representation, and that refusal is crucial.

Appetite does not attempt to stabilize Goa as a coherent cultural object. Instead, it treats the state as a site of pressure—ecological, political, linguistic, and emotional—where old forms persist uneasily alongside new economies of extraction, tourism, and attention.

Food, unsurprisingly, recurs as both motif and method. In Clyde D’Souza’s opening story, Sorpotel, a celebratory family meal curdles into violence, with class resentment, migration, and masculinity simmering beneath the surface. The story’s grotesque climax—where sorpotel, beer, and blood collapse into one another—refuses sentimentality. Food here is not comfort or heritage branding; it is volatile, excessive, and inseparable from power. That tonal refusal sets the register for much of the book.

Several stories use genre and speculation to interrogate contemporary anxieties. Pinto’s Eucharist is a standout in this regard, blending body horror, theology, and digital culture to devastating effect. Its central image—a vessel that endlessly feeds yet consumes its bearer—reads as an allegory not just for religious appetite, but for the economies of virality, surveillance, and performative devotion that increasingly shape public life. Crucially, this is not speculative fiction divorced from place.

The rhythms of monsoon, village labour, and parish life ground the story firmly in Goa, even as it gestures toward global structures of attention and belief.

Other stories attend more closely to domestic and social interiors. Pieces like The Real Housewives of Assagao and Seeking Shanti examine aspiration, migration, and the gendered costs of reinvention, often with sharp irony.

Translation also plays an important role: Damodar Mauzo’s The Cream of the Milk, translated from Konkani by Xavier Cota, is a reminder that English-language writing from Goa exists in constant dialogue with other literary traditions, even when that dialogue is uneven or fraught. The presence of translation here underscores the anthology’s attention to linguistic hierarchy and access.

The poetry section marks a tonal shift without breaking the book’s coherence. Poems here are quieter, more fragmentary, but no less political. They register endurance, loss, and resilience without resorting to slogans or abstraction. It is within this section that my own contribution appears: an illustration accompanying a poem by Tony De Sa. De Sa, whose fiction has been shortlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize, approached me personally to respond visually to his poem.

The illustration does not invite visual amplification so much as visual listening. The image does not attempt to “explain” the poem or translate its meanings into another register. Instead, it sits beside the text, allowing silence, spacing, and texture to do much of the work.

That collaboration matters less as a biographical note than as an example of how Appetite works. The anthology encourages conversation across forms—between writing and illustration, between generations of writers, between emerging and established voices—without collapsing those distinctions. In a book concerned with appetite as seeking rather than consumption, that distinction is significant.

The essays that make up the final section of the book broaden the frame further. They range from memoir and cultural criticism to meditations on stamps, dating, architecture, and diaspora. Vivek Menezes’s contextual essay on Goa Writers situates the anthology within a longer history of collective cultural labour, while pieces like "Craving for the Chic" and "Such Hunger for Hate" address the violent consequences of unchecked aspiration and ideological appetite. These essays are uneven in tone and ambition, but that unevenness feels deliberate. The book resists polish in favour of multiplicity.

What binds these disparate forms together is not the theme alone, but an ethical orientation. Again and again, Appetite asks what it means to want without entitlement, to belong without possession. This is particularly urgent in the Goan context, where land, labour, and culture are increasingly framed as consumables—whether by tourism, real estate, or nostalgic fantasy. The anthology refuses that framing. It insists on friction: between past and present, insider and outsider, care and exploitation.

The editors’ note makes clear that the process of assembling the book involved learning when to push and when to step back. That editorial restraint is visible on the page. Appetite does not smooth over contradictions or resolve tensions. It allows stories to sit uncomfortably beside one another. In doing so, it offers something rarer than a definitive statement: a living archive of voices thinking through Goa in real time.

In that sense, Appetite is a seismograph. It records tremors, like those of environmental collapse, cultural exhaustion, and creative resistance, without pretending to predict outcomes. Its greatest strength lies in this attentiveness. The book does not ask to be consumed quickly or neatly. It asks to be returned to, argued with, and sat alongside.

To seek, to reach for, to beseech: these are humble verbs. Appetite understands that humility is not the opposite of ambition, but its necessary condition. In refusing to offer Goa as spectacle or shorthand, the anthology makes a compelling case for contemporary regional writing as a site of ethical and aesthetic seriousness. It reminds us that appetite, when held carefully, can still be a form of care.

Over the last few years, public discourse—both online and offline—has increasingly framed Goa through binaries of insider and outsider, native and settler, protector and exploiter. These debates often collapse complex histories of migration, labour, caste, and colonial inheritance into blunt accusations or romantic claims to authenticity. What gets lost in the process is any shared language for responsibility: who consumes Goa, who bears the cost of that consumption, and who is allowed to witness, remember, or speak.

It is precisely here that Appetite feels timely rather than retrospective. The anthology does not resolve these tensions or take an easy moral position on who belongs. Instead, it reframes belonging itself as an unsettled practice rather than a stable identity.

Many of the book’s strongest pieces resist purity—of origin, of language, of cultural claim—and instead foreground inhabitation: living with contradiction, friction, and historical residue.

Goa emerges not as a possession to be defended or an aesthetic to be consumed, but as a place shaped by overlapping appetites that are rarely innocent and never evenly distributed.

This refusal to adjudicate belonging mirrors the book’s broader ethical stance. Appetite does not ask who has the right to Goa so much as it asks what kind of relationship one is willing to sustain with it. What does it mean to desire a place without exhausting it? To witness its transformation without aestheticizing its damage? To consume—food, culture, land, narrative—while remaining accountable to what that consumption erases?

These are not abstract questions in Goa today; they are daily negotiations, playing out in villages, courts, housing markets, and cultural spaces. The anthology meets that uncertainty head-on, offering literature not as verdict but as method.