Naga Delegates Confront Colonial Ghosts in Oxford

“We Are Here Now to Reclaim You”

They came not as tourists, but as mourners — pilgrims of memory and pain. From the mist-veiled hills of northeast India to the cloistered corridors of Oxford, 23 Naga delegates crossed continents last week with a single, sacred purpose: to speak to the dead. And to bring them home.

Their destination was the Pitt Rivers Museum — one of Britain’s most storied yet controversial institutions — long celebrated for its anthropological holdings, and long indicted for its complicity in colonial violence. For over a century, the museum has housed thousands of items taken under empire: weapons, ornaments, ceremonial attire. And, in the case of the Naga, the unquiet remains of their own ancestors.

They came face to face with them in a private room normally closed to the public — skulls, tufts of hair, fingernails, long bones, even the partial remains of a child no older than nine. There was no glass to shield these fragments. No ceremonial prelude. Just silence, and grief.

Some wept quietly. Others recited prayers in tribal dialects rarely heard in these walls. A few stood still, trembling. But all bore witness.

To the museum, these remains are catalogue entries — 41 ancestral skeletons and nearly 180 objects believed to contain human material. To the delegates, they are not things but people. Not exhibits, but spirits — fathers, grandmothers, warriors, children — abducted under the guise of science and empire. Spirits, they believe, still trapped in limbo. Spirits who cannot rest until they are returned.

“This was not a museum visit,” one delegate said later. “This was a reckoning — with the dead, with our history, and with ourselves.”

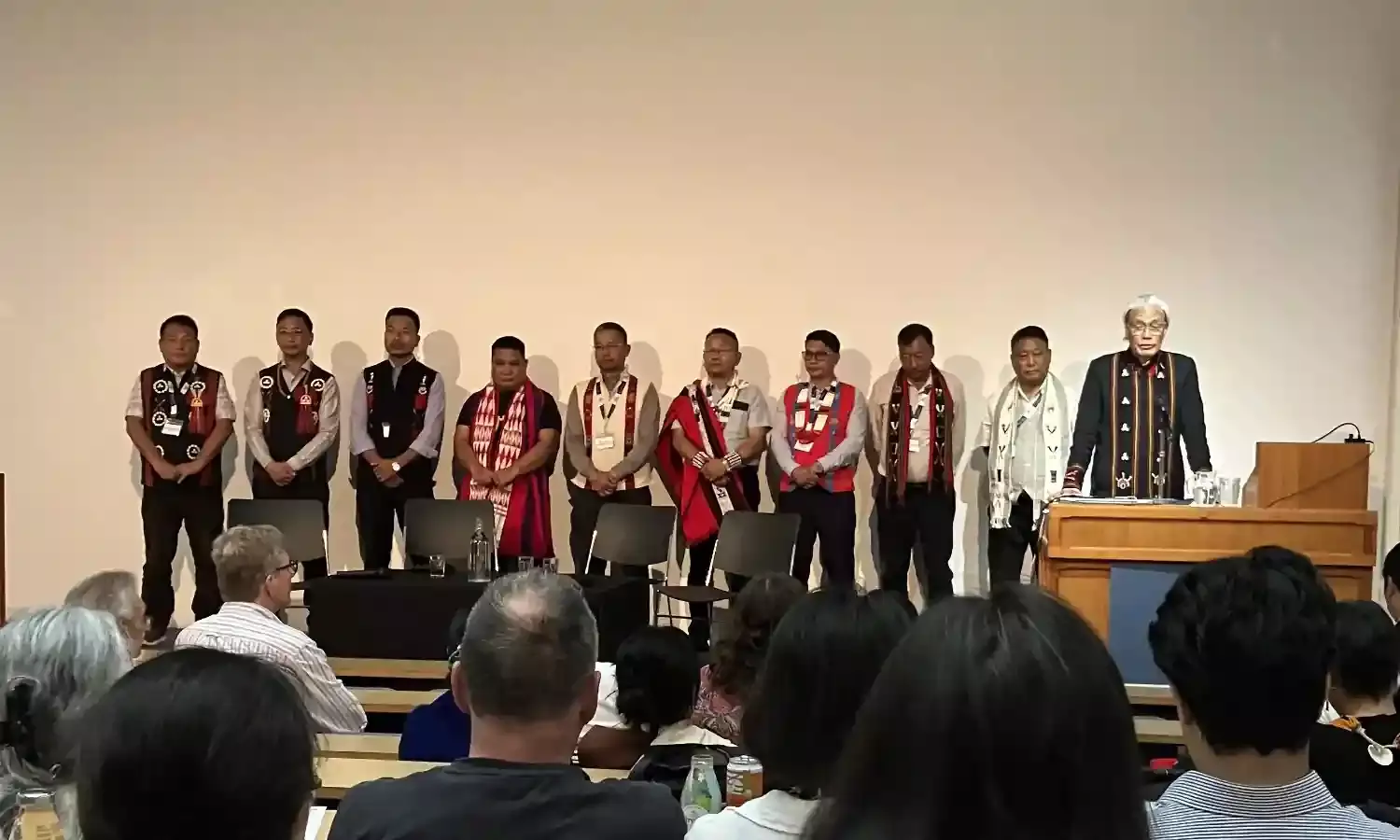

The five-day gathering, held from 9 to 13 June 2025, was formally described by the Pitt Rivers Museum as a workshop “to discuss repatriation of ancestral remains.” But for the Naga, it was something deeper: a long-overdue act of spiritual responsibility.

Dr Phyobemo Ngully, a psychiatrist from Kohima, explained: “If we don’t bring them home, our ancestral spirits will be restless.” He spoke softly, eyes wet, during a break in proceedings.

What they saw — and what they felt — is not fully reflected in the museum’s accession records. Delegates believe the actual number of ancestral remains is far higher than the official count — perhaps as many as 450 individuals — collected through raids, coerced exchanges, or state-sanctioned theft.

A century ago, this theft was described in the cold language of official correspondence. In 1923, colonial administrator James Philip Mills wrote of his desire to “loot” the Naga village of Yungya “to the advantage of the P.R.” — a shorthand for Pitt Rivers. “I should like to fire on it,” he wrote. “The men deserve bullets.”

Later, Mills confirmed in a letter that he had shipped a severed human head from Yungya via Calcutta. His colleague J.H. Hutton, also an anthropologist and District Commissioner, contributed photographs of decapitated skulls strung up behind his official residence — grisly trophies that eventually found their way into the museum's collections.

To generations of curators, these were "specimens." To the Naga, they are something else entirely: ancestors, forcibly displaced. A spiritual violation, passed down in silence.

“It is difficult to explain what it means,” said one delegate. “The pain is not in words. It is in the body. In the bones.”

Dr Laura Van Broekhoven, the museum’s Director, acknowledged this rupture. Speaking publicly during a Q&A and more candidly in a private briefing, she said: “What we want to do is work towards repatriation of human remains which should never have been taken.”

She admitted the process may take time. Returning ancestral remains to Tasmania, for example, took 40 years; the fastest case was resolved in 18 months.

“We are waiting for a claim,” she said. “Ultimately, it will be decided by the University Council. Personally, I will be very surprised if it does not go back.”

She described how other Indigenous communities had found peace after repatriation: “A lot of it is very joyful and very peaceful for communities who say these collections were taken without their permission.”

She confirmed that the Naga visit was co-funded by the Government of Nagaland and an anonymous philanthropist.

On the final day, inside the museum that once displayed their ancestors as objects of curiosity, the delegation read aloud a prepared statement:

“Where the mortal remains of our ancestors are never forsaken but always reclaimed… Our people eagerly await your return. So be prepared to make the journey home.”

A second document — The Naga Oxford Declaration on Repatriation, signed on 13 June 2025 — spoke to a wider mission:

“We are sorry that it has taken us several decades, but we are here now to reclaim and return you. We extend our solidarity in the hope of bringing decolonisation, justice and peace not just for ourselves, but for humanity.”

Some in the group reflected on older connections between the Naga and Britain — not just as victims, but as reluctant participants in imperial history. Around 1,000 Naga were recruited into the British Army Labour Corps during the First World War. During the 1944 Battle of Kohima, Naga scouts helped British and Indian forces repel the Japanese. These stories, held in both pride and sorrow, speak to a more complex legacy: a people both colonised and called upon.

In their presence at Oxford, that complexity came full circle. They brought with them the memory of empire — and the demand for repair.

The British Museum, too, now faces similar claims. But it is institutions like the Pitt Rivers, and museums in Manchester and Leiden, that are actively engaging with the wider global reckoning over colonial-era collections, including the Benin Bronzes and other looted heritage.

The Pitt Rivers Museum awaits a formal claim. If approved by the University of Oxford’s governing council, the Naga remains may finally begin their journey home — a journey that delegates say is as spiritual as it is political. There is no fixed timetable. Some past repatriations have taken decades. Others, less than two years.

But for the Naga, the timeline matters less than the direction of travel.

“Bless this land as you bid farewell,” the final line of the Naga declaration read. “And may your homecoming bring peace and harmony to our land.”