The Battle to Keep Children Cisgender and Heterosexual

Excluding non-cishet kids is harmful to everyone

Early last month the NCERT published a set of guidelines for teachers and school staff to better facilitate the inclusion of transgender and non-binary students in Indian schools.

“The soul of inclusivity is to allow students to study without discriminating them based on gender, class and caste,” an unnamed NCERT source told the media. “Even NEP 2020 emphasizes on the inclusion of transgender students in the education system.”

Seven days later it had taken down the manual, in response to social media trolling as well as a public objection from the National Commission for the Protection of Child Rights, controlled by the Union Ministry of Women and Child Development headed by Smriti Zubin Irani.

“The text of the manual suggests gender-neutral infrastructure for children that does not commensurate with their gender realities and basic needs,” the NCPCR chairperson reportedly wrote to the NCERT. “Second, this approach will expose children to unnecessary psychological trauma due to contradictory environments at home and in school.”

Among the complaints made to the NCPCR was reportedly one by former RSS pracharak Vinay Joshi, who called the manual a “criminal conspiracy.. to psychologically traumatise school children”.

Meanwhile schoolchildren are learning - and teaching each other too. High school student Vaishnavi Chopra, founder of the group We Don’t Hide Our Pride, says the only space queer children have to understand these concepts is outside of the school space. There is a lack of inclusion of students, because there is a lack of teaching on the matter.

“As a teacher your duty is to teach the students, not only about the syllabus, but also things that affect them in their lives,” says Chopra. “Especially if a student mentions it, then it should be taken up, because that means it definitely means something to them.”

And once the questions start coming, “Introducing an issue relating to the community is the easiest way to make the society more inclusive and to educate people, because schools are the primary source of education.”

As for the argument that Indian children are not ready to be told that there are many genders and sexualities,

“It really doesn’t make sense because nobody is born with information. If you give them all of the information that is required in the early stages, then everything is going to come to them pretty easily.

“In fact, once they grow up and start learning about the LGBTQ+ community when they are older - I think that’s going to be a lot harder.”

Chopra feels like very basic concepts can be introduced at the prior stages. “I think the curriculum can include more inclusive books. You know how little kids are given short stories to read, and they always talk about mother-father, never about mother-mother.”

And whether it’s learning about non-hetero people or other sorts of difference, “If it is making a community within your country happier, and feel safer, then I think there’s no problem with it.”

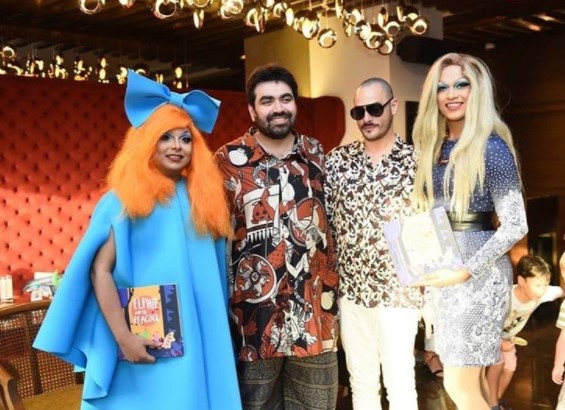

In 2019, OKO at The Lalit hotel in New Delhi launched monthly storytelling sessions for kids aged 5-10. These sessions are still in play and are hosted by drag queens. They are now attended by teenagers too.

“The very idea to start Drag Queen Story Hour was to create awareness and sensitise kids about the diversity that exists around us and build an egalitarian society,” says Akshay Tyagi, lead of Diversity Equity and Inclusion at The Lalit.

“Storytelling helps in not just sharing messages of love, care and hope but it also empowers people, it gives them a voice and their narrative gets a chance.”

Tyagi explains that in these stories, “Elphie, a rainbow-coloured elephant, The Lalit’s brand escort, who is gender non-binary, goes on this journey of self-acceptance and narrates these tales. The stories have inspiration from real-life people, from our team members, and the society at large - people who we think have been marginalised, therefore their voices need to be heard.”

Since being launched, Drag Queen Story Hours have reached schools and hotels in 8 different cities.

“It’s important to teach kids about their own body, gender identities and sexual identities, to enable empathy and ensure they do not fall prey to stereotypes.

“They need to understand that gender is a social construct and it is important for each individual to accept, understand and respect everyone,” says Tyagi.

“If children learn these values, chances are they will grow up to be emotionally healthy and mindful of everyone around them. Often teenagers and young adults battle with their own identity, as there has been no narrative on queer lives.”

Such systematic exclusion is harmful for all schoolgoing children, says Rajeev Anand Kushwah, a graduate student of women’s studies at TISS.

“This lack of representation also leads to building up stereotypes. Because education can really change the way we perceive society, how we perceive other people, and how we perceive diversity,” says Kushwah.

“Diversity regarding LGBTQIA+ people is not reflected - so that is very harmful because children grow up with that mindset, and they carry it forward in their adult life. If we have normalised masculinity and femininity, then why can’t we normalise gender neutral ways of addressing?”

He speaks of “the very strict binary that existed between what is masculine and what is feminine - in terms of the cultural activities I was engaged in.” He faced judgement at school because he enjoyed activities like arts and crafts, which were spaces typecast for the girls.

“Although my creativity was appreciated, there was always the fact that I cannot do something that is inherently feminine. It would be pointed out to me,” Kushwah recalls.

Even in the classrooms, girls and boys were made to sit separately. “If you are talking too much you will be made to sit between two girls - it’s like a shameful thing.”

What is the purpose of such segregation?

“It’s basically maintaining the status quo, and perpetuating patriarchy and cis-heteronormativity. Because schools are the places where we get a very explicit idea of what girls do and what boys do, with all these images of male doctors and female housewives, and textbooks that have been written by old professors 20-30 years ago...” Kushwah tells The Citizen.

He suggests including gender roles in the “value education” classes taught in school. Because while there are gender equality cells and collectives in colleges, few children get such knowledge or empathy in schools.

His schoolmates bullied Shubham Bhatia, now a communications manager in Ahmedabad, because of his sexual orientation. He had to eventually drop out in the ninth standard because of the trauma.

“I felt like an extraterrestrial, like this world is not for me and I am not for this world. For the most part I felt that bullying is right because that is what I deserved, and that’s how people who are different are treated.”

He thinks such teaching would have helped. “I would have been a totally different person maybe and wouldn’t even have to face the bullying. I would have known that there is nothing wrong with me.”

“The way that education has been going on in our country is very focused on the individual,” adds Bhatia.

He thinks school education in India is very goal driven, and does not give a lot of importance to a holistic development of children’s personalities.

In short, “If sexuality is not a goal, they won’t teach it.”

He takes the example of global warming, another emerging subject, whose teachers have had to learn new ways to convey it to students.

“Partner with NGOs. Train the teachers and only then you can train the students,” he concludes.

On the argument that Indian children are not ready for such concepts, he demands,

“Who are you to judge the capacity of Indian kids? If they can crack IIT and IIM and go to Harvard and every school possible in the world, then why don’t they have the capacity to understand different genders and sexualities?”

Bhatia adds that there are bound to be hurdles in this venture. “It is possible that some teachers may be homophobic. So it has to be a very comprehensive and structured process.”

And with the subject of gender and sexuality, people always think about the LGBTQIA+ community – but “it is very much about the straight people also!”

Nor is it an Indian or non-Western problem alone. “The whole attitude towards sexuality or gender, it is so deeply rooted in patriarchy and religion and everything - even in Western countries we have seen this, it’s not only a problem in India.”

“We have to identify the core of the problem,” says Bhatia. “For most students the core of the problem is not gender or anything, it is a basic instinct, because there are different kinds of people in the world.

“It is a basic instinct to bully someone. That is where you target first.. Once you kill that problem, then you can proceed to discussions about sexuality and gender.

“They might find it interesting also. You cannot just throw these concepts at people who have very different realities at home.”

Over at The Lalit, Akshay Tyagi agrees that parents need educating too. “In a lot of cases, parents are either unaccepting themselves or lack knowledge about these concepts.”

Whether at school or at home, he thinks that there are definite harms to keeping such subjects out of the reach of young children.

“Educating is the foremost step.. When we don’t talk about gender, sex and sexual identities with kids, they remain unaware and ignorant. This can lead to insecurities among queer students, bullying behaviour amongst others. An unfavourable environment often makes it difficult for queer students to attend school.”