Maldives -Justice for Ziyadha Naeem in Landmark Ruling 5 Years After Death

Raped by her husband

If the survivor didn’t physically fight back against the perpetrator, then it wasn’t really rape. So you can’t prove lack of consent without physical injuries

The hashtag #JusticeForZiyadha, was floated on Twitter in 2019, almost 4 years after the woman passed after making complaints of domestic violence against her in her household. This year, on the basis of her heretofore pending case and others, Maldives amended the definition of rape to include marital rape.

This arrived as a landmark decision for Maldives, as a significant step in fighting sexual abuse in the country.

Ziyadha Naeem had confided in the doctors and nurses who had treated her injuries about being raped by her husband, but had not been taken seriously. When the matter proceeded to court, the family denied these allegations. She had also reported to others on the phone regarding the physical and sexual assault her husband committed against her.

Humaida Abdulghafoor, co-founder of Uthema, an NGO based in the Maldives that advocates for gender equality and women’s empowerment in the country, explains that in October 2020, Naeem's case came within the legal remit of marital rape because her situation qualified as marital rape within the limited definition in the law at that time.

In the few weeks prior to her passing, Naeem had told her doctors at the Indira Gandhi Memorial Hospital in Male’ (after having been transferred there from Thinadhoo, since the severity of her injuries had worsened), that her husband had abused her even after their separation. IGMH is where she finally succumbed to her injuries.

Abdulghafoor stresses that applying conditions to marital rape dilutes its seriousness. “Marital rape is still rape in all circumstances!” she stresses.

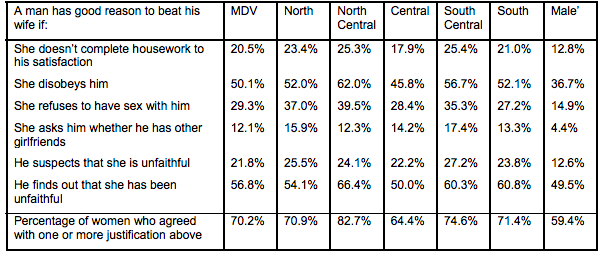

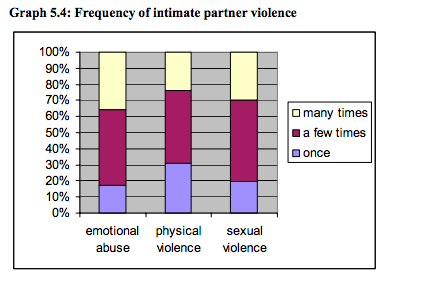

A survey conducted in Maldives in 2016-17, by the Maldives Demographic Health Survey revealed many a disturbing facts regarding the handling of sexual violence and rape cases within the country.

Women's responses to a questionnaire regarding domestic violence (released as part of an embargoed fact sheet for Maldives)

The survey found that almost all the women (92.9 %) agreed with the statement that ‘a good wife obeys her husband even if she disagrees,’ and that ‘a man should show his wife who is the boss,’ (78.9 %). These stigmas lead to a dearth in reporting of these cases taking place in the households.

Abdulghafoor says that, “Rape data on Maldives is inadequate, and not representative of the extent of the problem.” Expounding on the issue of reporting, she says, “There is a lot of cultural stigmatisation and victim blaming - within the family environment and the community.” She goes on to say that victim blaming is embedded in the law itself.

According to a news report by Maldives Independent on Naeem’s case in January of 2016, the family said, “The husband has a constitutional right to be considered innocent until proven guilty.”

“Talking about sexual violence is almost taboo, and perceived to be a private matter,” Abdulghafoor informs The Citizen.

She also reveals that the investigation process leaves much to be desired. Talking about rape kits for the investigation of sexual violence, she says, “We don’t have such practises here - there are investigation gaps…. Police training is inadequate and we have capacity constraints.”

“Due diligence needs to be delivered in these cases and the police need to get their act together!” she stresses. “So that the perpetrators can be held accountable and the survivors can access the judicial system.”

Abdulghafoor identifies this problem of sexual violence within the household as a “systemic issue that is linked up with the attitudes of law makers.” She points out that prosecutors, law enforcement officers, judges, etc. are largely men in the Maldives, and that reflects in the seriousness adopted when dealing with the investigation of these cases.

Maldives currently does not have any rape or sexual abuse helplines, barring one hotline that was implemented in association with UNICEF Maldives in 2017, that allows one to report instances of child abuse to the Ministry of Gender and Family and Police Services. And another line to the Ministry to report cases of domestic violence, which was implemented in 2020.

In a tweet, Prosecutor General of the Maldives, Hussain Shameem called it a “huge win” for the criminal justice system. Also adding that the accused has two more pending cases against him (possession of pornography and negligent homicide) before he can be put behind bars.

A case of attempted sexual assault in a safari boat in Hulhumale harbour in 2020, made everybody sit up and take notice of the fallacies in the rape laws of the country. This is incident prompted many advocates and lawmakers to suggest amendments to the laws on sexual violence. These amendments included the removal of a few discriminatory provisions in the Sexual Offences Act, Section 53 - also demanding the mandatory use of rape-evidence kits. These amendments are still pending before the court.

Divya Srinivasan, South Asia Consultant for Equality Now, provides a picture of the larger issue of sexual abuse in South Asian countries.

“Marital rape is not criminalised in India, so as of now I guess it is not all that different (from the Maldives), because marital rape cannot be reported to the police,” she says. Much like with Naeem’s case, Srinivasan says that there has been a case pending before the High Court for nearly six years, trying to criminalise marital rape, “but it still hasn’t happened.”

She details, “Recently, when the case came up before the Chhattisgarh High Court, they said that even non-consenual sex between a husband and his wife cannot be considered rape - because of the exception that is currently there in the law. Basically, there is no specific remedy for marital rape under the law. The only way you can approach the police is by probably filing a complaint of ‘cruelty’ under 498A IPC under domestic violence.”

Moreover, the compensation provided for rape victims by the Indian government, does not apply for survivors of marital rape.

Srinivasan also brings up the community pressure that is brought to bear on survivors who are from socially excluded communities in India. She sees this especially in cases of rape where the perpetrator of the abuse is from a dominant caste community and the survivor is from a socially excluded community. “There is tremendous community pressure on the survivor to stay silent.”

She also mentions that most of the delays in investigation take place due to the delay in the survivor filing a report with the police - even more so than the delays that happen due to the deficiencies in the medical examinations.

However, she says that the latter delay is far more avoidable - “Often survivors are made to wait for hours or even half a day, just in the police station, waiting to register their complaint. And even after that, there may be delays in getting the medical examination done….Most rape victims don’t even report their cases at all.”

Srinivasan opines that in considering South Asian trends of handling sexual abuse against women legally - “I think the Maldives amendments are more progressive. Earlier they had a provision which was specifically for cases of rape within marriage, which was very narrow - covering situations where the parties were divorced or separated, or there was transmission of an STD. They had a separate provision and a separate penalty,” she explains. “Now with the amendment, they have removed that provision completely and they have amended the definiton of rape to say that it is (will be considered) irrespective of whether the woman is married to the perpetrator or not - basically treating marital rape on par with all other cases of rape.”

However, she mentions that with South Asian countries like Bhutan and Nepal, where provisions against marital rape already existed, that “the penalities for marital rape are still significantly lower than the penalties which are there for other cases of rape within the law.”

“The law is still giving the impression that rape within marriage is not as serious an offence, and does not deserve the same treatment under the law as other cases of rape…. It’s still not in line with international human rights standards,” says Srinivasan.

She notes that in some other countries, such as in Latin America, as also has been detailed by the United Nations, “what we can see as the best practise standard is that - rape within marriage is treated as an aggravating circumstance while deciding the penalty. Because not only is it is a case of rape, but also a breach of trust between the parties that are involved.”

Speaking of the rape myths prevalant across South Asia she says, “What they try to do is, they try to shift the blame onto the survivor.” She takes an example of the same as reflected in the law, - “if the survivor didn’t physically fight back against the perpetrator, then it wasn’t really rape. So you can’t prove lack of consent without physical injuries.”

“Another myth is regarding the sexual history of the victim, wherein, if the survivor is sexually active, then she must have consented to the act as well. Whereas in reality, the past sexual history of survivors is completely irrelevant to the question of whether she consented to this particular act of sexual intercourse or not. Despite this, in most South Asian countries, they actually allow the introduction of evidence of the past sexual history of the survivor in rape cases….Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, all allow introduction of past sexual history of the rape survivor. Especially looking at Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, the law specifically says you can introduce evidence on the past ‘immoral character’ of the survivor.”

In explaining this she discusses the ‘two finger test’ which is an invasive medical examination procedure, still prevalent in some countries, legally and otherwise, including in India, despite repeated bans by the Supreme Court and guidelines issued by the Ministry of Health. “Basically, (this test) is a vaginal examination of rape survivors, which essentially involves a doctor inserting two fingers into the vagina of the rape survivor, for two reasons - first is to check if the hymen is still intact, and the second is to test the laxity of the vagina- and it’s extremely unscientific on both these counts.”

Srinivasan expands that it has already been proven that the existence or lack thereof of the hymen is completely irrelevant - women could have a torn hymen for many reasons including exercise and physical activity; and even someone who has been subjected to rape may have their hymen intact. And secondly, she says that many examining doctors will report that two fingers were easily inserted into the vagina, and this is taken to suggest “that the victim is habituated to sex.”

Abdulghafoor mentions that she hasn’t yet encountered any evidence of the two finger test being in use in the Maldives, and only became aware of it as recently as last year, in the course of her advocacy and research.

Srinivasan agrees with Abdulghafoor in that, “We still have a long way to go in terms of changing social mindsets, as well as gender sensitisation of the police, prosecutors and judges in order to make sure that marital rape criminalisation does not just remain on paper, and actually has an impact on the reality of women’s lives.”

“This is a huge step. And we hope that this will set a precedent for the handling of such cases in the future as well,” says Abdulghafoor in conclusion.