‘and it became a struggle’ - Interviews with Ambedkarite Artists

We are oppressed by our casteist upbringing

As the establishment strives to maintain a hellish status quo, and the few unaffected people turn a blind eye, some artists are steadily working against casteism and caste. The Citizen interviewed three such artists, who share the view that art is a means to educate society.

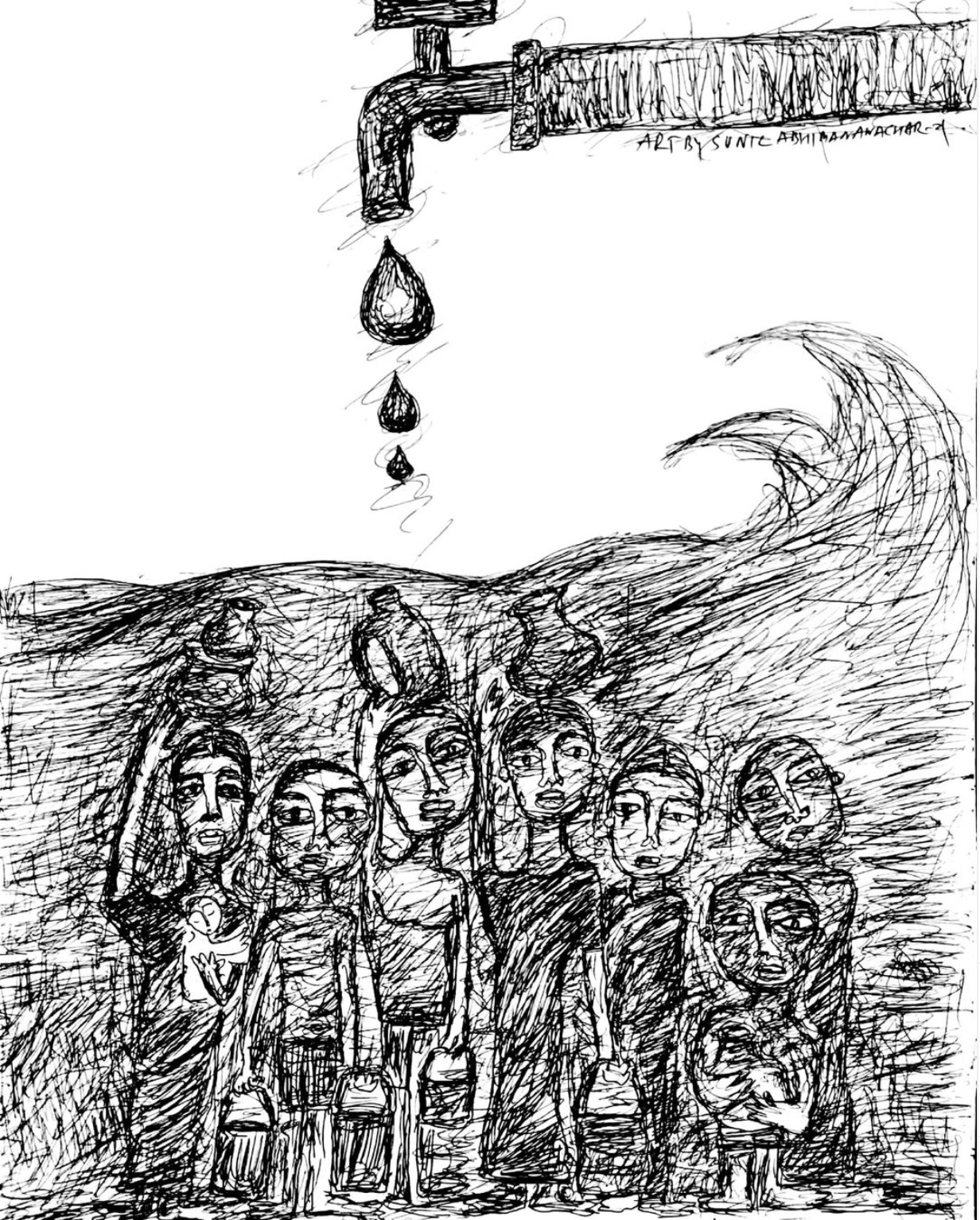

Sunil Abhiman Awachar is an artist, poet and activist, and teaches Marathi literature at the University of Mumbai. His poetry has been read and artworks displayed at many Dalit led protests across India.

He says his art is “all about the violence against Dalits before and after Independence, and the discrimination faced by Muslims, the LGBTQ community, and Dalit Bahujans.”

Awachar’s introduction to politics started early. “My grandfather was very involved in Babasaheb Ambedkar’s movement… There was a culture of this movement in our household. So the issue of caste has never left me. I have seen examples of this at every turn in my life.”

“Caste is already a political subject,” he replies.

“I have always been judged based on my caste… When I was young and used to go to meet girls that I liked, there was always a question about my caste. Then when I came to Mumbai for my job I was about 30, I assumed there wouldn’t be such discrimination in a city like Mumbai. But even then, when I arrived at my department on campus, even there people asked about my caste, and it became a struggle.”

He says “A poet or an artist is a cultural leader. Through art and language they bring a different culture to the public. Politicians and others become leaders in society through the government, and we lead through culture.”

“I consider myself a soldier, a cultural soldier,” he says, speaking of the intention behind his art and poetry. “I feel like a social activist, and I don’t just speak about Dalit issues through my art and poetry. However, the respect and acknowledgement has to come from the upper classes, because they run the society.”

“As long as we as a country do not develop the ability to be sensitive, we will not be able to achieve the society that we desire,” says Awachar. And he thinks that despite the bleakness there is certainly a silver lining.

“The people sitting in the art galleries, they do not like to give credit to artists like us, they would rather ignore us… But I know that my art is being taken up as a part of the protests and uprisings. My art and poetry has been exhibited at protests like Rohith Vemula’s case, the farmers’ protests and many others. My poetry and art stands with them.”

Awachar recalls an encounter with the media, where also powerful positions are squatted by a handful of castes. “I recently wrote a critique on an Ambedkarite piece of art. I took it to a friend of mine who is from an upper caste and works at a big media house, and I asked him if he would publish it.

“He was almost shocked that I suggested he publish a critique piece written by a Dalit. They can carry art by Dalits but not a critique written by them. That time felt really bad.”

Awachar worries that the reach of art from Dalit points of view is being confined to an echochamber.

“See the thing is, violences against Dalits, women… it’s happening all the time in our day to day lives. The upper classes judge us and say, ‘Oh they have begun again, they are talking about the same things, nothing new.’ But it’s not that our voice is only restricted to our groups. If only there is some sensitivity in an individual, they will understand what is going on with us.”

“I have heard many a time people will say, ‘Why are you all crying about the same things?’ But if someone from an upper class can look inward and analyse oneself, they will understand the inherent casteism in their lives, they are sure to see it. But they do not do that examination.”

As for what it might reveal,

“They do not think of us as human beings who are part of the society! They are not ready to think of us as people who have lives and beating hearts and are crying. So how will they understand our art and literature?”

“If they do not consider us humans, how will they consider us artists? They tend to judge and neglect our voice. They judge the language we use because to them it sounds alien and therefore inferior - and they wonder why we keep on talking about negative and depressing things through our art and literature.”

“Our work breaks that barrier of the status quo, and that makes them uncomfortable.”

For instance, Awachar says that Dalit literature is historically characterised by voicing the community interest, not the interest of the individual. “It is about the ‘our’, not the the ‘I.’”

Nevertheless, all things considered, he says he is a hopeful man by nature. “Dalit literature has to be seen from a different lens, and from a different ground… With social media the reach has diversified and the audience has grown. Where earlier Dalit writers were unable to find publishers, now the situation is different… I feel that we can see change through this.”

“This isn’t my career or even my passion,” he replies, when asked what role his work plays in his personal life. “I do not want to throw a light on me and my personality through this work. I would rather stand as a part of the movement.”

UNTOUCHABLE MUMBAI

Sunil Abhiman Awachar

Babasaheb said: the village is the rotten den of casteism.

Without caring much for life

To appease my historical hunger

I enter this grotesque city.

I embrace the footpaths adjoined to highways,

Some of us have got jobs

In the blood sucking factories,

Some of us are made to sweep and clean

The gutters of municipality at the cost of our lives

Being here is like suffering with the agonies of hell

Or being an orphan lost in the dreadful city.

Some people say Mumbai is the door of heaven

Others say it is the city of dream;

But when we ask for our share after toiling hard

We get kicked on our arse.

Today sixty years have passed since independence;

The new age of digitalization is being celebrated.

Our pockets are filled with enough money and

It seems as if we are accommodated in the mainstream;

But when we want to buy a flat in the high tower in Mumbai

They suspiciously ask us: Who are you?

It we tell them our real identity

They make their faces and say: No.

l am standing beneath the shower

Rubbing the soap all over my body

But the stain of untouchability

That stuck inside my skin as if a membrane,

Seems impossible to wash out.

Mumbai must have offered prosperity to them

But to us, it does not allow a living

without first burning in the hell of caste

Swapnil More is the drummer for Dhamma Wings, a Buddhist band that sings Ambedkarite ideals and Buddhist principles.

The band has been playing for around 10 years now, and their rise to fame has seen its share of struggle. “We have had a lot of good stage performances,” says More, recalling the time they performed at the Gateway of India on Ambedkar’s 125th.

He shares that the founder of the band, Kabeer, spent three years as a monk in Sri Lanka, which had a great impact on what he projected through his writing. “He thought, ‘why don’t we spread this message through music?’”

And the message,

“Ambedkar’s most significant contribution was that he spoke of equality. His messages were about equality and secularism. We have so many religions and castes in India, and that makes equality an important subject. We have a song called Peaceful which is an anti-war composition and we have made a few compositions on this theme as well.”

More thinks that music makes it possible to reach out to people who cannot read or write, and cannot join the written discourse of universities or citizenship. “The music will hit them in a way that words in a book cannot. See, even movies have music, songs - it is the easiest and a more effective way to communicate emotions to an audience.”

Three of the band’s four permanent members are from Dalit Mahar families who converted to Buddhism.

“There were very few bands in the past who spoke of the subject of caste and equality, and even artists who did were mostly performing classical genres. But after our band came into the limelight, people are singing on these topics through rock music as well, and it has become much more popular now.”

“And this is a good thing!” he exclaims. “Young people are learning about Babasaheb and his teachings, as well as taking an interest in rock music.”

He says that if even more artists choose to speak on social and political topics like these, rather than producing music for entertainment alone, our society has the potential to grow much faster.

More says that in his experience of the music industry the most challenging factor has been finances, and discrimination by casteists is not as prominent as before.

“In comparison to generations before us, my experience has been that caste barriers have gone down significantly in cities like Mumbai,” he says. “We are full time musicians, so we do end up taking commercial gigs from time to time. Even with those, we haven’t felt a lot of caste discrimination.”

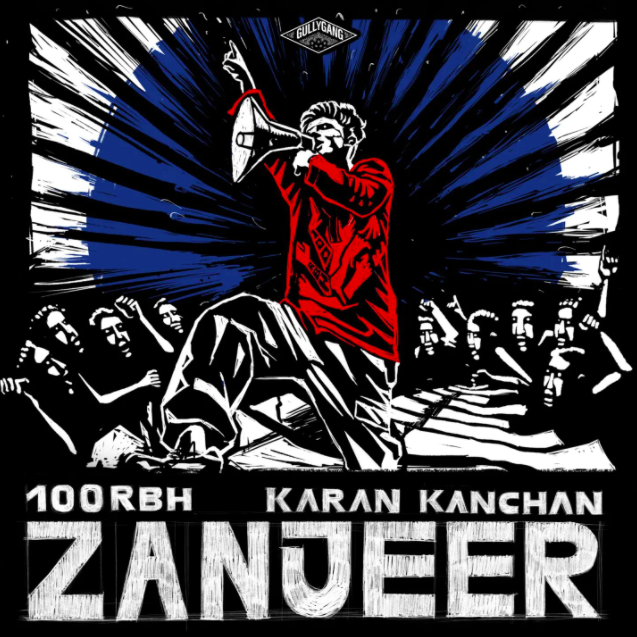

Saurabh Abhyankar, who goes by the stage name 100RBH, is a 25 year old rapper based in Mumbai. Casteists first discriminated against him in his childhood, which is also when his interest in hip-hop began. His rapping career started near the end of 2013 and he is now part of the Gully Gang collective, who were recently featured in the Amitabh Bachchan starrer Jhund.

“I used to really like to dance as a child. Before rap, I was more of a dancer. I used to find it all very cool - the loose clothes they wore and the stunts they did.”

His first exposure to rap was when he saw Pradip Kashikar rapping in Marathi on TV. “Because Kashikar used to rap in my mother tongue, I also felt that even I can actually rap in Marathi.”

“Initially I used to mostly write about my city. Then gradually I learned more about hip-hop. And I have been listening to Babasaheb’s songs since I was a child, and those songs were always reflective of reality to me. That is how I started taking an interest and rapping about other issues as well.”

Asked what made him rap about sociopolitical issues he says, “When I started learning about hip-hop I learned that they used rap to rage. And just like they have racism in the West, I have also seen and experienced casteist discrimination since I was a boy. It all felt the same to me.

“The way Tupac used to write for his society, I also wanted to write about my people. And since I have been listening to Babasaheb’s songs for years, those were the kinds of ideas that always occurred to me.”

He says his neighbourhood friends were also influential in his introduction to rap music.

“At first when I started rapping in Marathi, I was able to make some friends who also already knew more than me about rap, and they told me about all these Western rappers. Three of us then, Darpan, Anurag and I, made our rap group Rap Hopper. I didn’t know anything about Tupac and all of hip-hop history before my friend Anurag told me about it. But once I found out about hip-hop culture it all felt very familiar.”

Abhyankar thinks the problem with caste has historically been a Dalit problem, and has still not seeped into the psyche of others.

“You know, many a time we hear people saying that caste discrimination is no longer a big societal issue. But that is only because it’s not being shown to the public! If you actually take a closer look, there is an instance of crimes against Dalits almost every month. And these are the ones that we hear about! Often these cases are not even allowed to come to the surface. Most of them do not have the confidence to go to the police or the media, so they stay buried.”

He says raising a voice to draw attention to these erased figures is of vital importance.

“Those living in fear still are the ones who do not have any access to an education or an agency. It is easy for people to say that everybody has the agency to protest. But that is not the case. For instance, even if we say that in certain remote areas sexism is dying out, the ground reality is far more nuanced - because even if girls are allowed to go to college, they are not allowed to take all the classes that their brothers are allowed to take. The cultures will take time to see change.”

Abhyankar feels deeply about the music he makes and that is what drives him. “If I am trying to tell a story people might not be interested. But if I put it in rhyme, many more people will take notice. If I was inspired by the rappers before me, I feel like I should also put my thoughts out there for this generation. If I bring the reality out then maybe it will have an impact. My weapon is my music.”

Has discrimination ever deterred you from your mission?

“There is not a lot of open discrimination in my circuit, but I still feel it in the small things. It does not scare me anymore because this inherent discrimination has become a constant since childhood.” But that does not mean he is at all comfortable with it.

“So this has become normal for me actually. Because I know that even if I am in the right, it will not be seen because of the caste factor. So if someone brings it up as a problem, I say - Move over, I have work to do. This will keep on happening.”

It has helped him move forward in his career. “Earlier I did not understand the business and distribution side of things at all. But now since I have some record labels backing me, I have to worry less about getting my stuff out, and I can concentrate more on writing.”

He says rap has emerged as an important tool to educate the younger generations. “In our generation, very few people choose a course in life and then stick to it. Even if people start studying a subject, very often they do not delve into it outside of their studies. But what hip-hop does is, it looks and sounds cool, which is attractive to young people. So it’s easier to get these social issues to them through music and rap. They get to enjoy while also learning and getting inspired.”

Even so he thinks it will take some time for rap to be understood as a tool for social change.

“People are largely listening to music for entertainment. People in 9-5 jobs on their way home from work want to listen to music to unwind and be entertained. They do not want to get a reality check at that time, it annoys them, because it compels the mind to think deeply about these issues. People mostly look at rap as entertainment still, and want it to remain that way. So if someone wants to be inspired they will be, and for the others, they can just skip ahead to a different song.”

He adds that while there is still a long way to go, he does appreciate those who appreciate his message and music. “It feels nice when people write to me saying that one line in a song, or a particular song hit them very deeply. It feels right.”

“If I achieve a lot on any given day, and I don’t also write or compose something that day itself, it all starts to feel futile to me. So I will just focus on writing and getting my message out, and the rest will hopefully fall into place.”