Caste in Muslim Indians

‘Those we vote for are afraid to take our name’

An interesting discussion at a recent conference on the caste census showed that casteism is shared by Hindus and Muslims in India.

The panel, on Caste and ‘The Muslim Question’ with sociologist Khalid Anis Ansari, demographer Srinivas Goli, activist and former MP Ali Anwar Ansari and historian Faisal Devji was moderated by researcher Shireen Azam.

Azam studies the state and policy discourse on caste among south Asian Muslims.

“Waking up as a Muslim in India in the last 8 years has not been easy. Every day the news somehow manages to get even worse… Something about the sight of schoolgirls in Mangalore wearing saffron scarves to show their support for the banning of their classmates in hijab shows us that things have gotten way worse than they were just yesterday.

“And this is the relentless everyday context that we live in. And amidst this, people who work on caste in Muslims are often asked, is this important at a time like now? …It’s not so bad as among Hindus, right? Muslims are not killed based on their caste right?”

Azam hoped the panel would discuss, “Why caste is not just a feature some Muslims may have in some degree or more, but how information on caste communities in India might help us think differently about Muslim educational backwardness, the lack of Muslim representation in government services, the powerlessness of Working Class Muslims in the face of atrocities by lynchers and police, and why some issues are considered more muslim than others.”

She said the first census in 1871 argued that Upper castes (Syeds, Sheikhs, Pathans and Mughals) were only 19% of the Muslim people of India. “If caste has historically determined what kind of jobs people are able to do, what industries they are in, where their houses are and whether they get to study, what is the status of those 81% of Lower caste Muslims today?

“If you were to believe NSSO data, most of them have magically turned into Upper castes. According to the Sachar Committee, which used NSSO 2005 data, OBC and Dalit Muslims constitute only 40% of Muslims.

“So the questions then are: What are we not seeing about Muslim backwardness as a result of not having a caste census? What are we missing about Muslim ghettoisation, about atrocities on Muslims? And what will change for the Muslim identity in India if there is a fresh caste census – what will change in the way Hindutva attacks and speaks of Muslims?”

Khalid Anis Ansari began by “historicising the Muslim question.

“There is an influential body of work that in the precolonial period communities and identities were much more fuzzy and ambiguous, and from about the late 19th century the colonial knowledge project, particularly the instrument of census, gazetteer, maps, museums etc, reconfigured south Asian society from a religious lens. So these fuzzy communities became much more systematised, bounded, aware of their numbers and position vis à vis other communities.”

There were “two other moves with serious epistemic consequences on how we understand south Asia today. The first colonial move was that it launched religion as the overarching category, and accommodated all the social diversity, whether caste, gender or sectarian affiliations, intepretative communities, within the category of religion. Caste in particular became an internal moment of religion, and there was a religionisation of the political sphere.”

“The second important move was that Hinduism was framed as a tolerant but inegalitarian religion, and Islam on the other hand was framed as an intolerant but egalitarian religion. And these two conceptual moves have continued to inform how we understand south Asia”.

“One can see the conceptual violence of categories involved here, in which the pan religion, high caste Elite play the role of the native interlocutors. And from the early 20th century, especially after the Montagu Chelmsford reforms and semi parliamentary politics were introduced, there was an anxiety among the high caste sections across religions.”

This was because they are short on numbers.

“They constitute minorities within all religious communities. And in order to respond to this anxiety they – the Ashraf and the Savarna class in Hindus and Muslims, in both these communities – invisibilised their privilege and also their demographic deficit through the category of religion, and became the self styled spokespersons of both the Hindu and Muslim communities.

“The Savarnas became the spokespersons and self appointed leaders of the Hindu community, and the Ashrafs became the spokespersons for the Muslim community. And due to various reasons the colonial regime obliged.”

After the Partition. “If you look at the postcolonial framing of the Muslim minority discourse, or the Muslim question, there are three key elements that were foregrounded. The first was the question of identity as solidarity, and here the Muslim community was presented as a monolithic community, an egalitarian community… There was emphasis on vertical solidarity, the unity of all Muslims.

“Second was the question of equity, and here the entire Muslim community was presented as a marginalised community, an oppressed community. The third key element was that of security, of periodic communal violence that affected the Muslim community.”

These elements were challenged by the Pasmanda movement.

“In the 1990s the emergence of the Pasmanda counter discourse – a movement of Backward, Dalit and Adivasi Muslims who claim they are about 85% of the Indian Muslim population, a majority within the minority so to speak – challenged these three key elements of the Muslim minority discourse, and deconstructed it as a mechanism serving the interests of the Ashraf, High caste Muslim classes.”

“In terms of identity, the Pasmanda discourse suggested that Muslims are not monolithic, they are internally divided on the basis of caste, and that Islam as interpreted in the south Asian context is not really egalitarian, there are deep seated caste hierarchies here, which are also legitimised by the religious communities, texts, that were produced in south Asia.

“In terms of the entire Muslim community as a subaltern or backward community, the Pasmanda counter discourse suggested that during the last 50 to 70 years, during the Congress regime in particular, it was not all Muslims who were backward. A small microscopic minority upper caste elite was cultivated by the Congress party, and had a share in the Congress patronage system, and these classes were in no sense backward or socioeconomically marginalised.”

He said the Pasmanda movement had “advanced some data on the representation of Muslims… If we look at the Muslim body politic, the Ashraf categories are particularly overrepresented in the power structures, and underrepresented in the catalogues of victims of communal violence.”

The movement “articulated an alternative notion of solidarity. Instead of vertical, on the basis of religion, a counter hegemonic solidarity of pan religion subjugated castes. A solidarity of lower castes, of marginalised sections.”

Ansari said a complete caste census was a very important moment “to test these claims of the Pasmanda movement and ground them on the basis of more scientific evidence.”

“We all know caste is not a static category, it is dynamic, and the relationship of caste, class and occupation was not watertight even during the colonial period.”

He said the British census reports discuss the “question of fission, fusion, of various Lower castes presenting themselves as Upper castes as a status enhancement mechanism.”

“In the 1931 census it clearly notes that Sheikhs and Pathans have returned inflated numbers, and one of the reasons is probably that the occupational castes have returned themselves as Sheikhs and Pathans.”

“Such data needs to be updated… One has to take stock of the dynamic state of caste and its relationship with class and occupation… A number of castes were left out in 1931 and new castes have emerged, some have fused into larger groups.”

Fresh data would help us understand these changes.

“The second major issue is the question of development. How to target the beneficiaries of welfare and redistributive measures? More germane to the Muslim question is the categorial revisions, the justice claims advanced by Dalit Muslims, Backward Muslims, Tribal Muslims… We have no sense of the population of these groups as of now, and if some credible data emerges it will be very helpful in understanding the categorical revisions.”

He said Dalit Muslims and Dalit Christians have asked to be included among the Schedule Castes, and Vann Gujars and Meo Muslims among the Schedule Tribes. Further, similarly placed caste groups across religions would need to be accommodated in the Other Backward Classes.

“This is not possible without scientific data, and there has been a ping, pong going on between the judiciary and legislature, and a caste census would be very helpful in resolving that.”

The last issue Ansari discussed was “competitive victimhood”.

“Much water has flown since the last caste census in 1931, and there are now some legitimate claims from higher caste sections like Pathans, Rajputs etc that because of neoliberal politics and the general functioning of the market mechanism, some of these landed communities might have slid down the class ladder.”

“There is an abyss, a kind of a gap between the historical memory of privilege that these castes have and their contemporary socioeconomic reality. They are on a decline… This might lead to hurt sentiments, and probably these landed communities are much more prone to restorative violence, communal violence and so on, one issue where the caste census will help.”

“Second is the question of graded inequality, where the hegemonic classes in India pitch one backward or subordinate class against another, as seen in the discourse against Yadavs, Jatavs, etc. So the question of upward mobility within lower caste communities also needs to be documented, because some of these upwardly mobile lower caste groups are attempting to invisibilise caste, to counter stigma. And are now increasingly wanting to be included in the consumerist paradise, neoliberal fantasies and so on.”

“And the question of castes’ endogamy. We need more credible data on intercaste and interreligious marriages.”

Ansari concluded, “Even during the colonial regime the Upper caste Muslim and Upper caste Hindu organisations contested and agitated against the caste census. But interestingly in India caste was dropped after independence, while religion was retained. Since then especially the fertility question and the comparative population of religions has fed into the Hindutva conservative imagination. I think the caste census is central to a new dialogue on the way our democracy needs to be conceived.”

Srinivas Goli, who teaches population studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, presented the results of a recent survey of 7,000 households representatively sampled across the regions and districts of Uttar Pradesh, cities and villages.

It studied untouchability, education, employment and poverty among Hindus and Muslims, their position relative to each other, and the position of Dalit and Backward Muslims relative to other caste groups.

Funded in part by the ICSSR, a government body, it used the socioreligious groupings and occupational categories found in the reports of the Mandal Commission and Sachar Committee, mapping subcastes (jatis and biradaris) onto the officialised categories of SC, General and OBC.

Goli said that we need to count caste because the inequalities within these large groups are growing, as are the inequalities between them. And with the growing demand for reservation by many economically and politically dominant castes, to better redistribute capital it would help to identify the most deprived communities of the officially deprived.

“We don’t have data to demonstrate this, only mechanisms to estimate it. We can’t say which caste is deprived, we can’t take the name, because we don’t have that kind of data.”

He said that not being a sociologist he was using categories like jati and biradari as reported, classing them as subcastes “for convenience”, and drawing an unexamined parallel between Forward Caste, OBC, Dalit and Ashraf, Ajlaf, Arzal.

These last are claims made by south Asian Muslims about their blood descent, and broadly correspond to their class position. Ashraf or upper class Muslims claim long ago foreign descent, Ajlaf Muslims are thought to be Hindu converts though not Dalits, and Arzal Muslims are treated as Dalits who converted to escape the rigidities of caste hierarchy.

Goli said his work had found identical occupations, caste names, socioeconomic backwardness, and similar experiences of untouchability amongst Dalit Hindus and Arzal Muslims. “We found a lot of subcastes which we classed as Arzal… The Government of India order of 1936 used ten socioreligious criteria to identify depressed classes in Hindus, and we found similarities using three parameters.”

But without a caste census there would be no robust evidence of their size, socioeconomic status, social exclusion or discrimination. This was important as Arzal Muslims are denied the affirmative action constitutionally guaranteed to Dalits, while most Ajlaf Muslims do not make it to the statewise lists of OBCs.

Goli said he had encountered strong criticism of a caste census “within JNU, a very powerful and politically conscious institution.” That it may trigger more divisions within communities, perpetuate caste feelings, “a large section of scholars think this will strengthen the caste system,” may weaken internal unity among Muslims, OBCs, Dalits, “and affect their political bargaining power, Savarnas can use it as a divide and rule thing,” and that it is “time to forget caste and live as a casteless society.”

He said that several Dalit scholars had also argued that “this kind of subcaste level information is not necessary… I agree that people can misuse these numbers to weaken the lower caste movement and to reduce their share of resources… But the reality is of heterogeneity, and we should address caste heterogeneities.”

He said the Census remained the gold standard of demographic data because “despite problems the enumeration is complete and it’s not a survey which can come with sampling errors… direct collection of information on caste is important.”

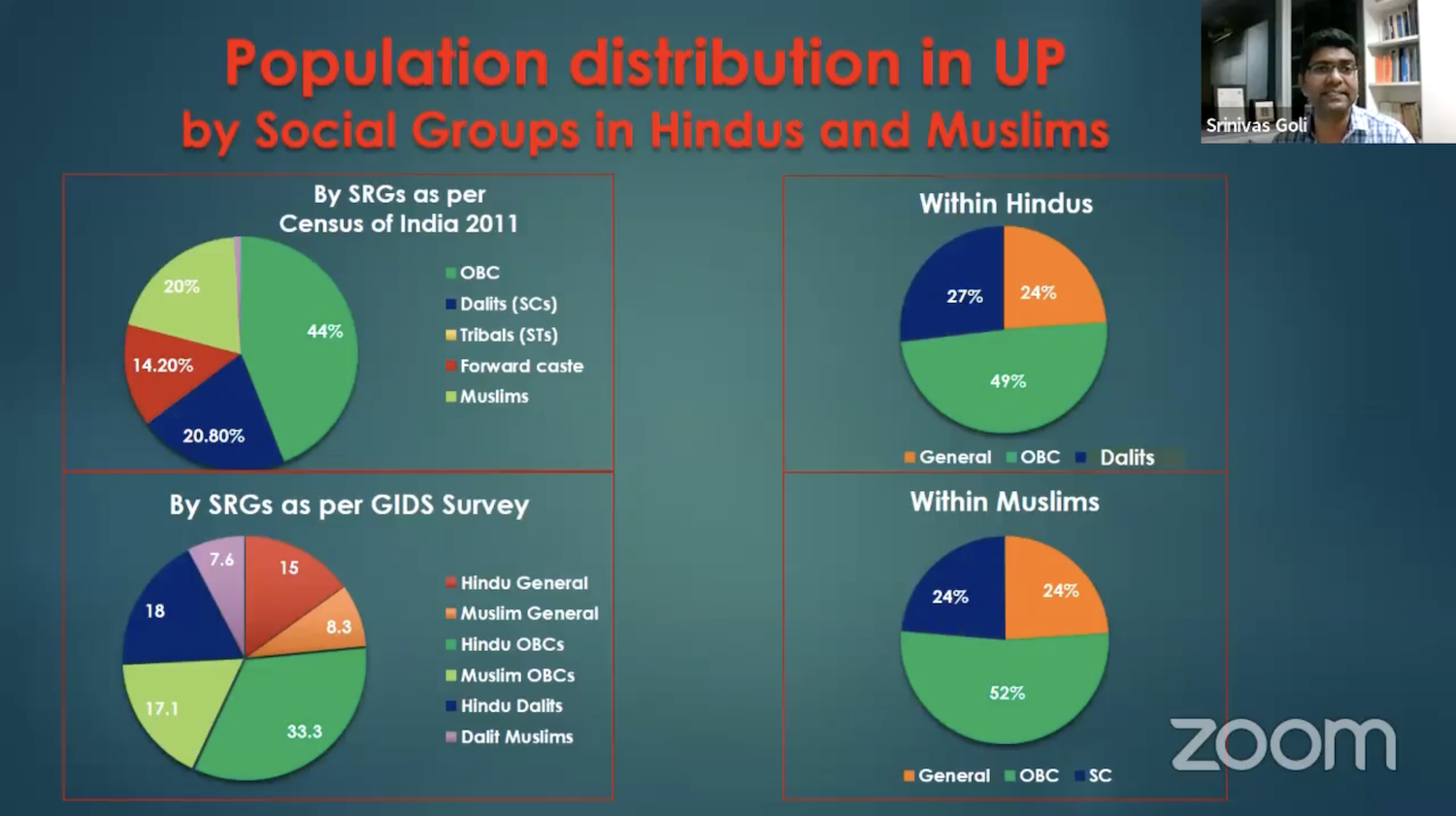

The pie on upper left shows the Census population of the administrative categories FC, OBC, SC, Muslim and ST in Uttar Pradesh. Lower left, this caste data is partitioned by religion, as found in the survey conducted by Goli and his colleagues. On the right, the Forward Caste, OBC, Dalit population share among Muslims and Hindus

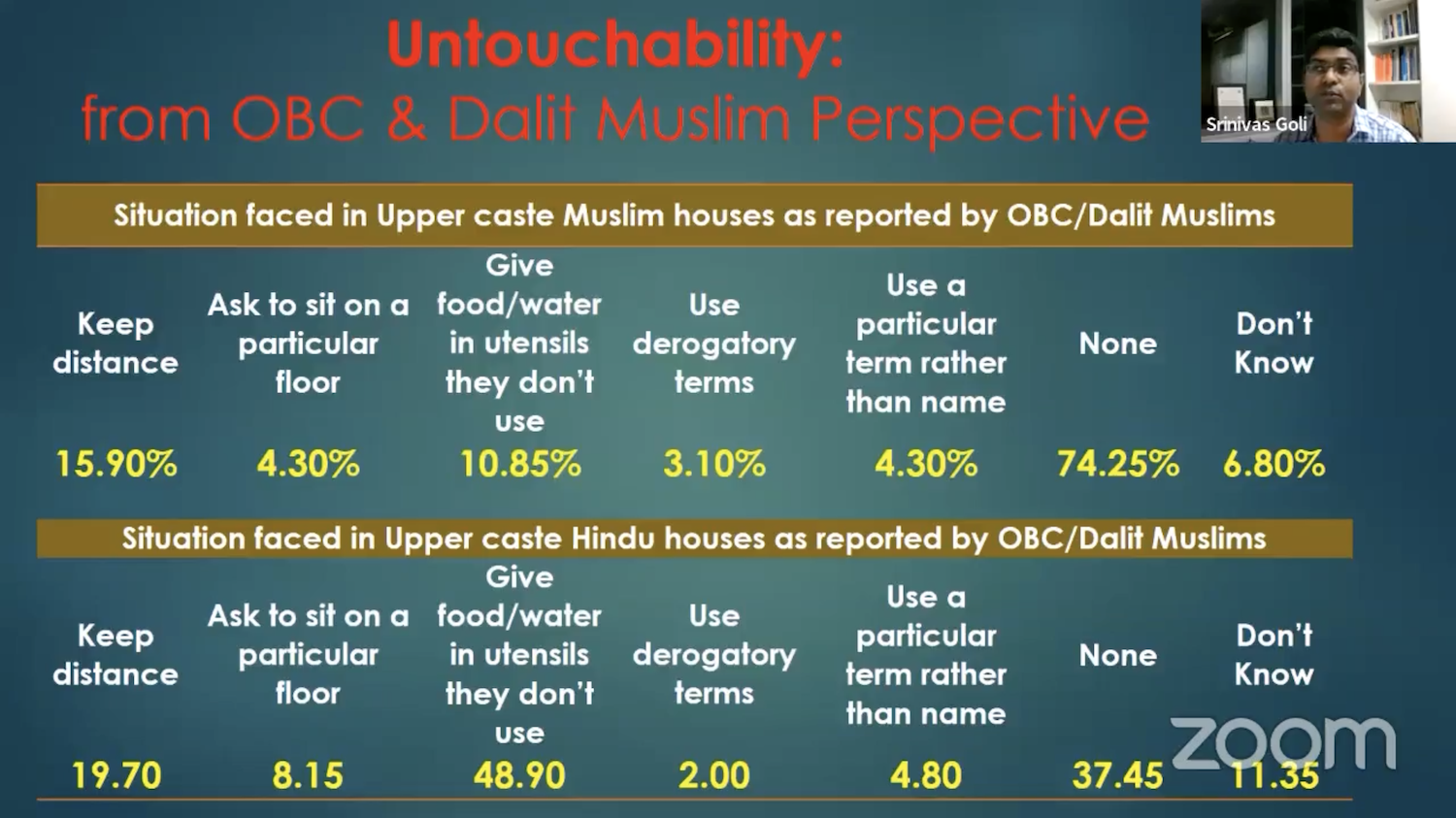

On many metrics OBC and Dalit Muslims reported a similar incidence of untouchability perpetrated by Upper caste Muslims and Hindus, with some exceptions. And while a large share of respondents said they faced no untouchability at the hands of Upper caste Muslims, the specifics reported were largely the same

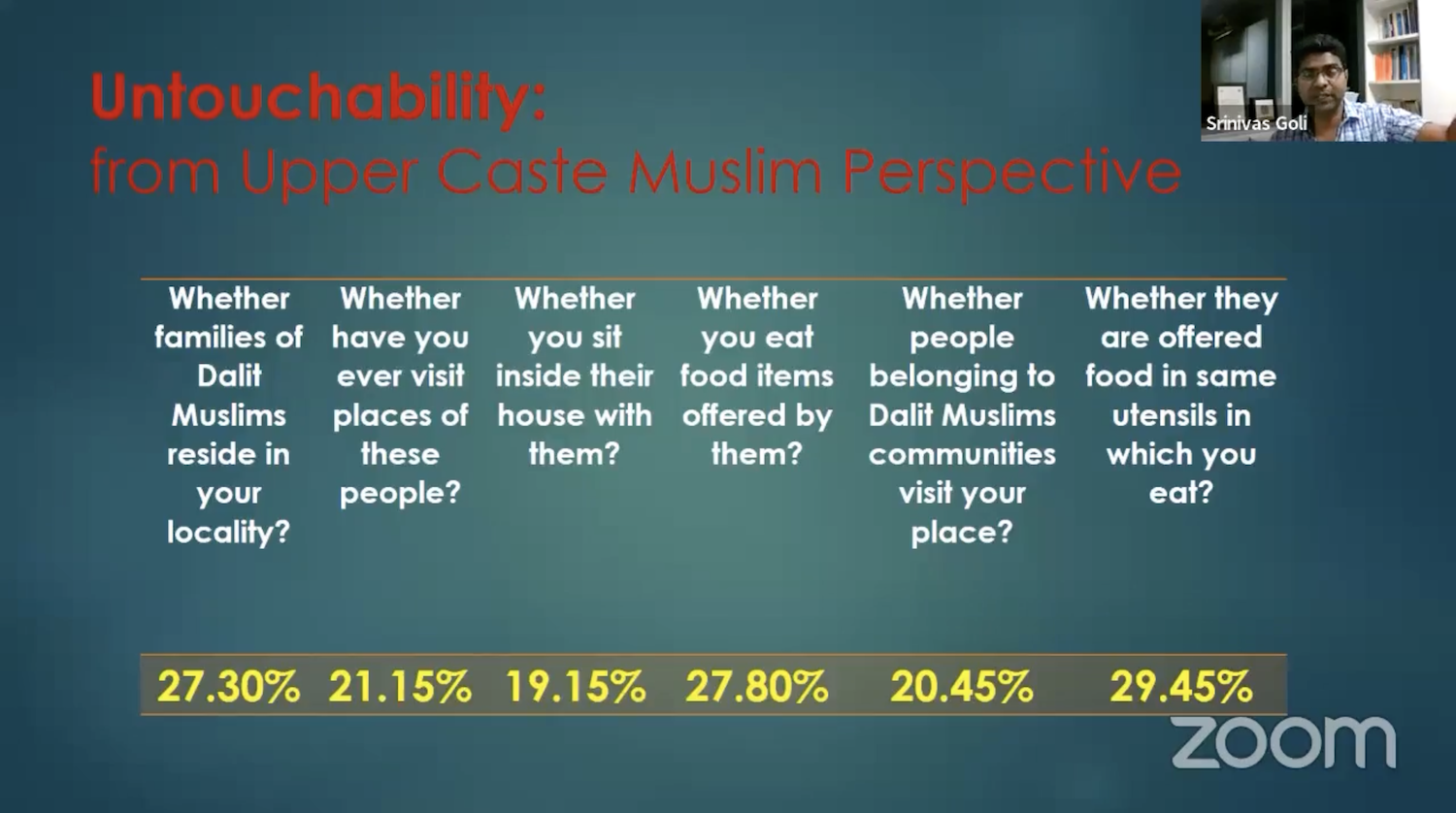

Muslims classed as Upper Caste by the researchers reported a low level of interaction with those classed as Dalit

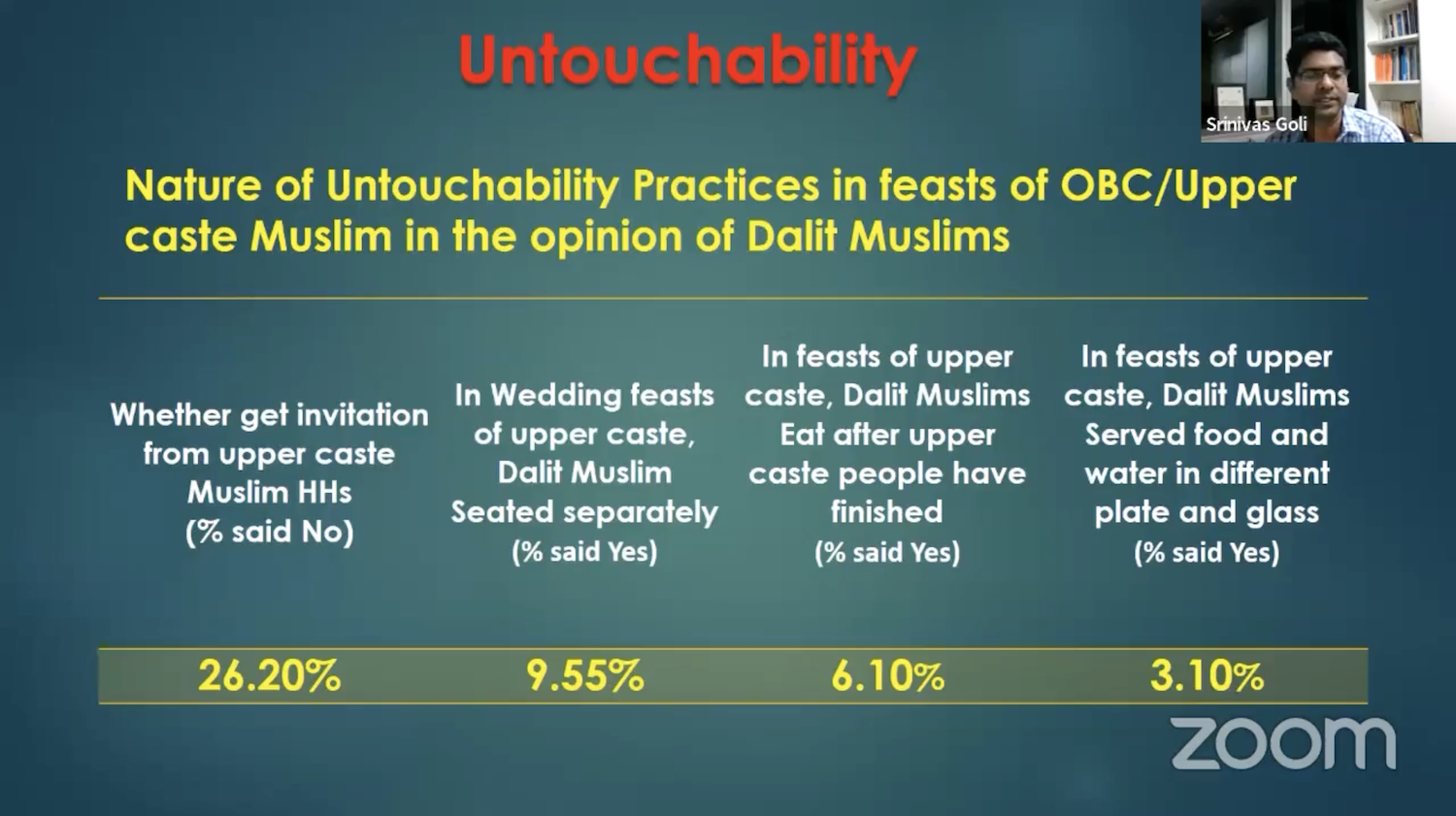

Prevalence of some untouchability practices perpetrated by OBC and UC Muslims as reported by Dalit Muslims

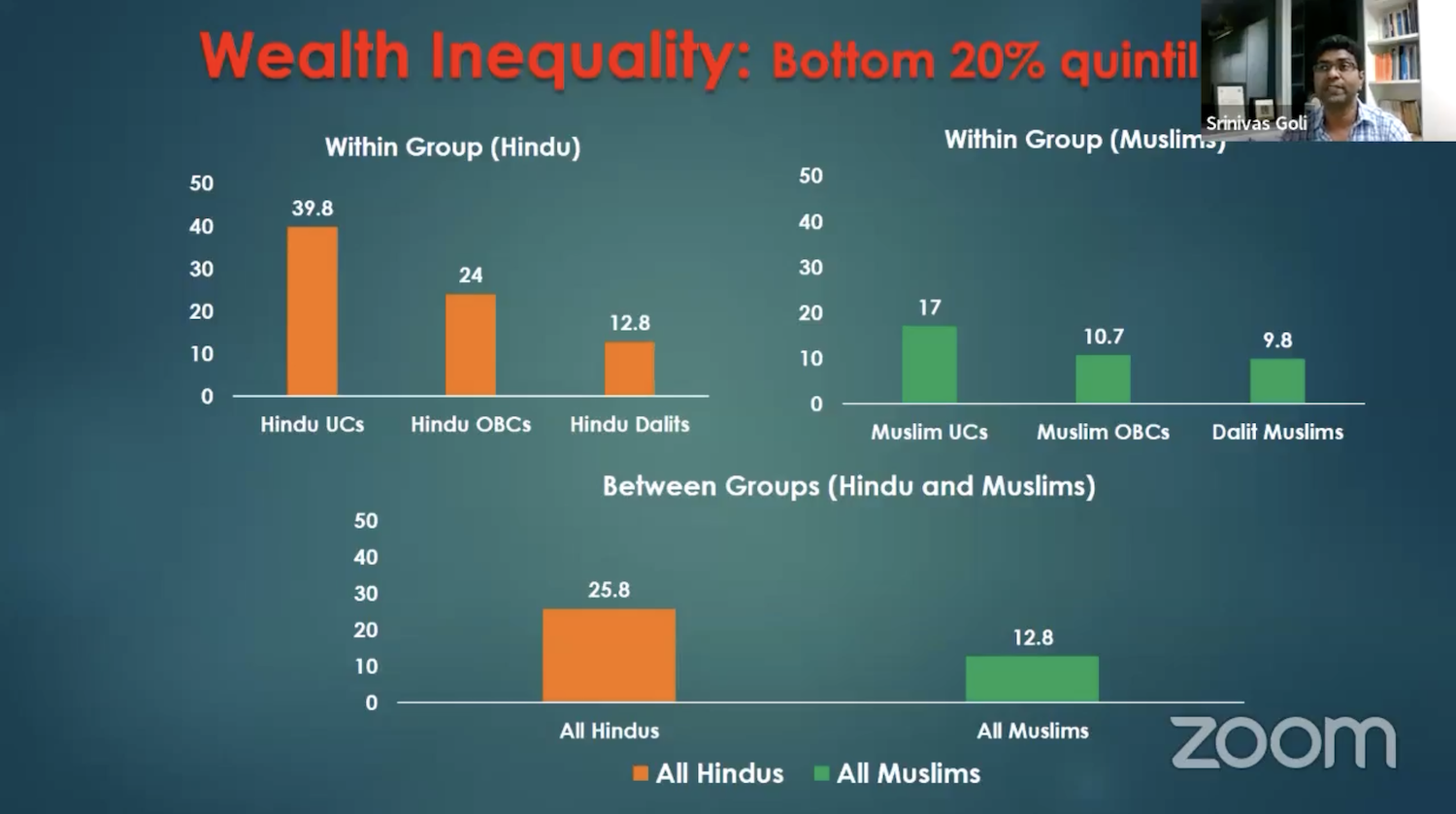

(Slide should read Top 20%) Wealth inequality among Hindus far exceeds that among Muslims

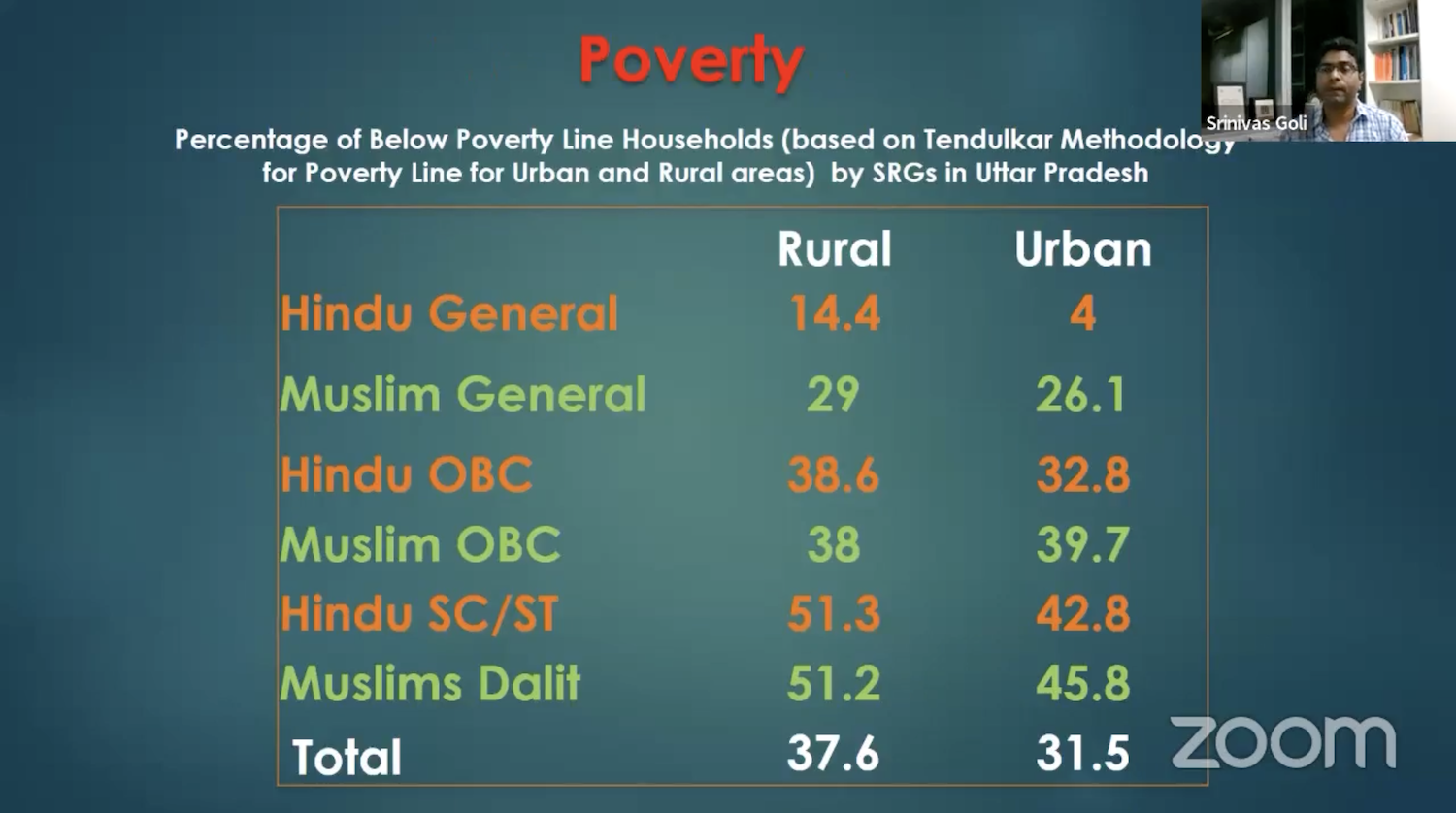

The extent of poverty was near identical among Dalit Hindus and Dalit Muslims, and among OBC Hindus and OBC Muslims. Poverty was far more prevalent among Upper Caste Muslims than Upper Caste Hindus

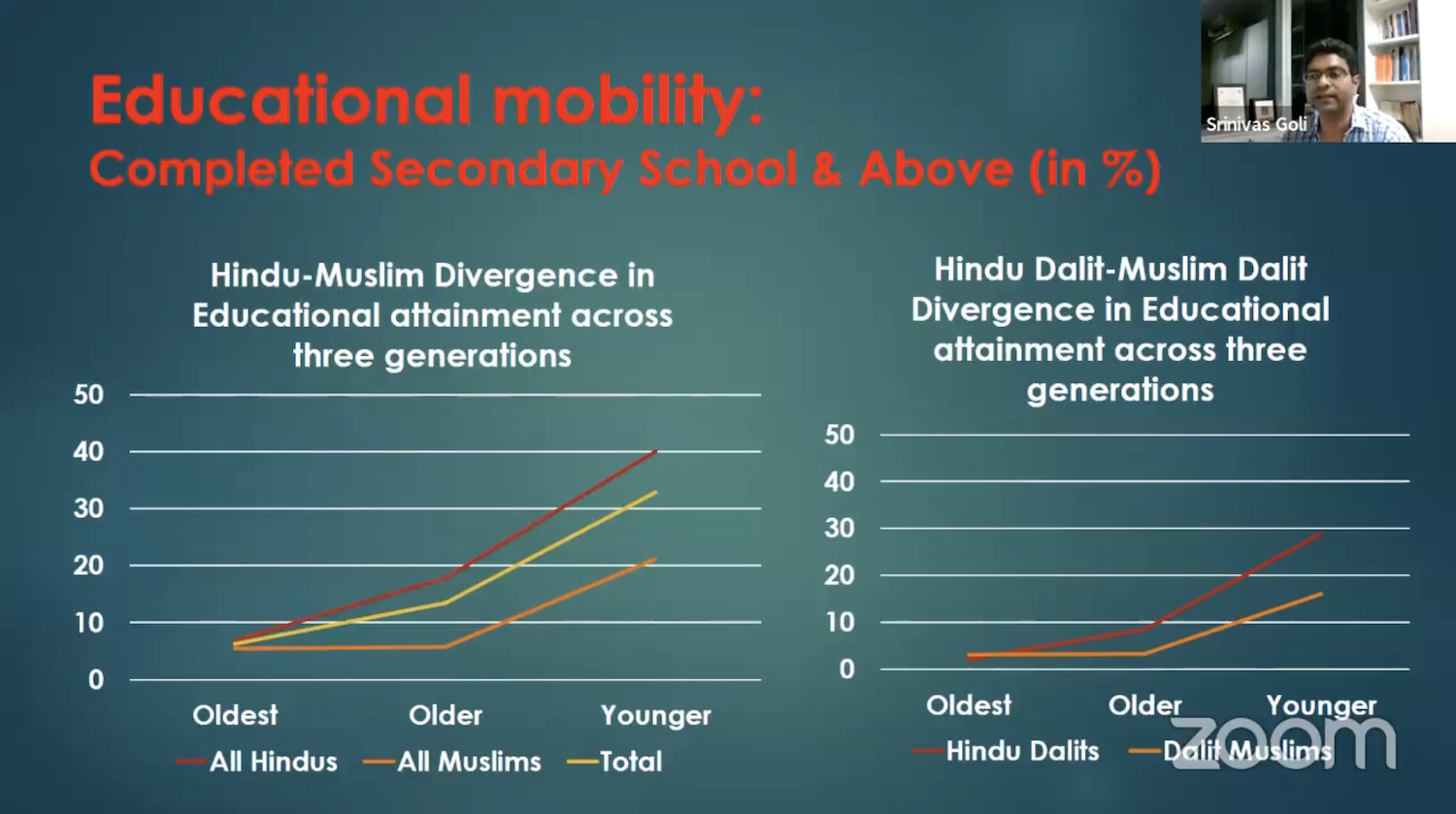

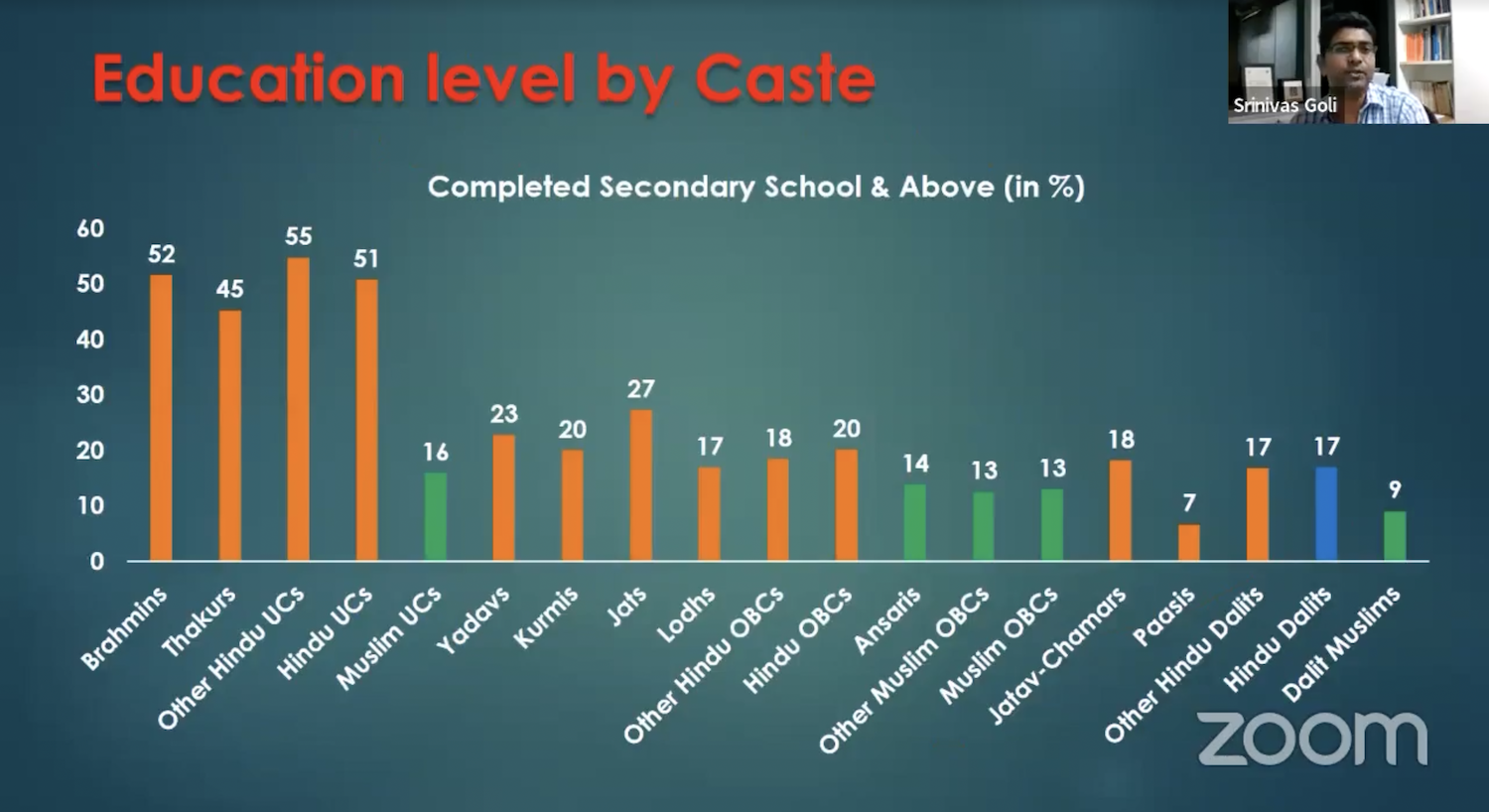

Among Muslims and Hindus, the oldest generation of respondents had similar opportunity to complete an educational degree, and with younger generations the divergence kept growing. Among Dalits, Muslims started off with slightly better educational attainment and the younger generations of Muslims were increasingly denied access to education

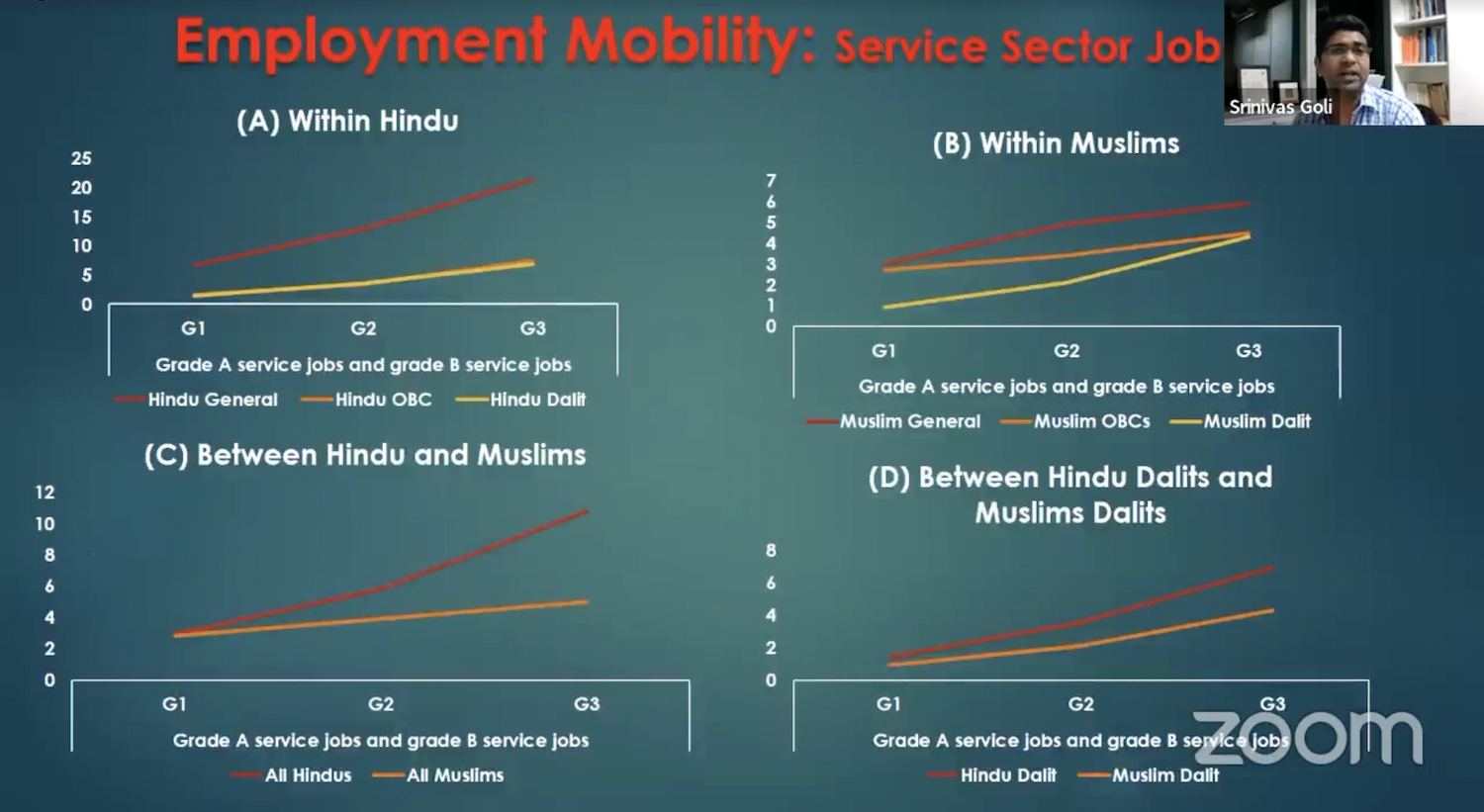

Among the oldest generation (G1) the divergence was least between religions and castes. With history Hindu Dalits came to be kept out of Grade A and B service sector jobs, as did Muslims overall. The divergence grew least between Hindu and Muslim Dalits

Hindu Upper Castes dominate the secondary and higher education market, private and public

Goli proposed that the state’s denial of affirmative action to Muslim Dalits and OBCs had hurt their ability to counter casteist oppression after converting.

And concluded, “The gap between Hindus and Muslims in socioeconomic status is persistent and significant… Including Dalit Muslims in affirmative action policies is an urgent and essential need.”

Ali Anwar, former Rajya Sabha member whose book Masawat ki Jung (war for-of-by equality) led the rise of the Pasmanda movement in the late 90s, spoke in Hindi=Urdu and his remarks are translated here.

“Since 1998 the Pasmanda movement we began has entered the academic discourse in India and abroad, in such a short time, and I am happy as it isn’t a long time in the life of a qaum or samaj, that too in Oxford, Columbia, Berlin and many Indian universities including JNU.

The caste census should be for the people of all castes in all religions, but I think a caste census among Muslims is even more important, because there is a negation of it in Muslim society, people don’t believe it, grand intellectuals deny caste among Muslims, and there is a practice of hiding and suppressing it among Muslims so it’s all the more important.

It is a question of upper caste hegemony in society - in Hindu and in Muslim society - and the effect of it on politics is that in the secular parties, and the parties that talk of social justice, there is an element of negating Muslim caste that is very strong.

As an example, this recent letter by Bihar leader of opposition Tejashwi Yadav to chief minister Nitish Kumar - the Congress is included in it. ‘If a caste census is not done the economic and social development of the Backward and Most Backward Hindus will suffer…’

Consider the irony. The parties that talk of social justice, not only regional but national parties like the Congress, CPI, CPIM, CPIML – from the letter it would seem that only Hindu OBCs (Bihar has Annexure 1 and 2, Most Backward and Backward) should be counted in a census.

After we pointed it out these parties amended themselves, though it wasn’t done in ignorance but deliberate. They are afraid that if we talk about caste among Muslims it will hurt us, they too think Muslims are monolithic and homogeneous, and are very keen that Muslims should remain so. This is one of the troubles with a caste census.

It doesn’t end here. Taking a step back, these parties talk of a caste census but say that an OBC census should happen, as the letter says, and Muslims are left out. But even among Hindus they only want to enumerate OBCs and EBCs, that is to say, not General. Such a caste census will have no meaning. Unless you count people in the General category it is meaningless…

Second, the ruling BJP’s Rajnath Singh said in Parliament that we’ll do an OBC census in 2021, just as the opposition letter says. But there was nothing about the General category or its subcastes.

On December 8 2009 I raised the question for the 2011 Census in the Rajya Sabha. The OBC, SC, social justice line parties all were there. When I raised it in a special mention not a single party member supported us, there wasn’t a sound… But by the next session in May 2010 the movement took shape, with Lalu Yadav, Mulayam Yadav, Sharad Yadav, and when these leaders take it up the MPs started too…

Gopinath Munde of the BJP also supported adding a ‘caste’ column to the next Census. So it was during UPA 2 that it was accepted, in principle. Then the way they messed with it was they didn’t do it under the 1948 Census Act, under the Census Commission, but delinked the caste census from it. So a caste census happened in name but it was so defectively done that the data was not released, either by the UPA or the NDA.

The reason was that they delinked it from the Census Act. The 1948 Act says that trained teachers should do it, but instead anganwadi workers, daily wage workers, NGO workers were enlisted as enumerators, and as a result people untrained in census enumeration performed it, so no good data came out. And what did emerge was hidden, suppressed.

Then on 9 May 2011 in the Rajya Sabha again I raised the question, but a lobby was at work. With the UPA the fear was that a caste census would lead to demands for an increase in quota - the OBCs whether Hindu or Muslim only get 27% reservation, and they’ll ask for more. The NDA has an additional fear, that a caste census will suppress their communal polarisation agenda, and it will sink to the bottom.

So we started educating people, like with this slogan - sampradayik dhruvikaran ka yahi ilaj, jati janganana ke liye ho jao taiyar - The only cure for communal division, prepare for a caste census. We started educating them. As activists we work as activists, you are academics and you work in your own way, we took these pamphlets to the field.

Dalit pichda ek samaj, hindu ho ya musalman - Whether Hindu or Muslim the Dalit Backward is one. As the All India Pasmanda Muslim Mahaj we went to thousands and thousands of people, from Delhi Lucknow Bihar Haryana, various states especially in the Hindi speaking region, and launched this booklet. Our non Muslim allies in the Jati Janganana Karao Abhiyan too spread this booklet, titled Jati janganana karani hogi, nara netritva naukri bachani hogi - We’ll have to get a caste census done, to protect leadership opportunities and jobs.

From NDA to UPA to those in the middle, who are nowhere, everyone is saying that if the Centre, the government in Delhi doesn’t do it the states should. Nitish Kumar says we’ll do it, Akhilesh Yadav says we’ll do it, but we say it is not a census if one state does it, only a survey. And its legal validity is not the same as a census done by the Census Commissioner under an Act of Parliament…

Surveys you could have done before, Mulayam, Lalu, Nitish, you ruled for 15-20 years, why didn’t you do it any earlier? And so they say it will only enumerate OBCs, or only be performed by the states – but if it’s statewise, what will happen to the jobs in the central services? …It should be done for the whole nation and we are running movements for it.

The upper castes including Muslim upper castes are against it and won’t want to do it. Obviously not, they know the share they grab in government jobs, in politics, everywhere else. It will expose their deceit.

It is true that 1931 was the last caste census but in 1941 too a caste census was begun. With the Second World War it wasn’t completed, the data didn’t come. But while it was underway the Hindu Mahasabha was saying, ‘Get them to write Hindu, not your jat’ and similarly the Muslim League was saying, ‘Get them to write Musalman, not your biradari’… Barring a few progressive people it’s the same situation today.”

Speaking last and briefly, Faisal Devji, who studies 20th century Muslim intellectual history suggested some more ways of looking at caste and religion.

Of the colonial period, he said it was “not increasing religification in colonial times of identity, but rather the shift to Islam and Hinduism as systems, as sociological systems, and that happens with the loss of indigenous kingship, where caste becomes the foundation for Hindu ‘identity’, and sociology and law, this so called Islamic law, becomes that for Muslims, and it’s these two things that become the foundations for claims to unity in both sides.”

Of the project of Muslim unity, he recalled the “fascinating genealogy with Syed Ahmad Khan. He has no interest in Muslim unity, he is interested in caste unity, between upper caste Hindus and Muslims… By the time of the Muslim League you do have Muslim unity emerging because of the introduction of elections… And then of course with the Congress you have exactly the same idea of Muslim unity. There is no difference between the Muslim League idea of Muslim unity and the Congress’s idea of Muslim unity. And it’s not a very politically productive idea at all today, I agree.”

“There is also an interesting alternative history of caste debate within Muslim politics. The first idea for caste reservation for Hindus is proposed by the Muslim League in 1906, to of course fragment the idea of a Hindu community. But even with someone like Muhammad Iqbal, who constantly writes about caste… it’s an interesting alternative history to be explored.

“Coming finally to the issue of religion again, I entirely agree that caste needs to be made visible in Muslim politics and in the so called Muslim community, but I wonder if it’s possible to do this without actually fragmenting the idea of Muslim religion as well.

“I don’t mean in sectarian terms. I am thinking of recent studies like Joel Lee’s ‘Deceptive majority,’ on the Valmiki caste in northern India, formerly known as Lalbegis. In Dr Goli’s presentation they are listed [also] as a Muslim Dalit caste.

“Lee shows that claims of religious identity, even excessive claims of religious identity as Hindu, do not stand up to scrutiny. I would think the same is probably true for groups classed as Muslim lower castes. I think you can’t really make caste visible without at the same time inquiring into the religious identity, which also requires some degree of fragmentation.”

The first question was about how Ashraf led groups like the Jamat-e Islami Hind, the Jamiat Ulema-e Hind, the All India Muslim Majlis-e Mushawarat and the All India Muslim Personal Law Board have represented Muslims and affected the Pasmanda movement in India.

Khalid Anis Ansari answered, “Before independence the Muslim League was characterised as Ashrafiya, an organisation of nawabs, capitalists and aristocrat classes, and was challenged by the All India Momin Conference, especially after the 1937 provincial elections and the 1940 Lahore Declaration where the Muslim League stated the demand for Pakistan quite openly.

“So there was contestation between these two… Then in the 1946 elections, dubbed as a consensus on Pakistan, from Bihar out of 40 seats (there were separate electorates at the time) probably the All India Momin Conference won 5 or 6 seats and the rest were won by the Muslim League.

“An important point to stress here is that in the 1946 elections there was a restricted electorate. Not everyone was allowed to vote. There was no universal adult franchise, so only a small section of Muslims were eligible to vote. There were qualifications for voting in terms of income, education, etc.

“So there is a sense that of the 13% [of Muslims] who voted for Pakistan, for the Muslim League, because of the correlation between caste and class most of them were probably Ashrafs, and the 85% or more of the Lower caste Muslim vote was not even put to test. So this entire understanding that Muslims are responsible for Pakistan does not hold true if we scrutinise it historically.”

In terms of Partition and the demand for Pakistan, he added, the Jamiat Ulema-e Hind was split between two camps, one led by Mahmood Madani, who articulated the idea of unified nationalism and a composite culture, contesting the idea of Pakistan, and the other led by Ashraf Ali Thanawi who sided with the Muslim League.

And today, “All these organisations are mostly dominated by high caste Muslims, and they endorse the broad Muslim minority or Ashrafiya discourse I pointed out earlier.”

A question was posed to Srinivas Goli on the differences in wealth and land ownership between Muslims and Hindus.

“The Muslim presence is disproportionately in urban India, so agricultural landholding is not quite relevant. But overall, wealth wise, whether it’s Hindu Dalits versus Muslim Dalits, or OBCs, or General, or Hindus to Muslims overall, there are multiple disparities as my research papers in the public domain have shown. There are also disparities in financial inclusion and equality.”

Shireen Azam. “Your data shows Muslim backwardness is not only Lower caste backwardness. The Upper castes are also backward.”

Srinivas Goli. “There is Muslim backwardness. The within-group inequality is significant and growing, but the Hindu-Muslim inequality is also significant and growing.”

He emphasised that his research had found identical or similar occupations followed by Dalit Muslims and Hindus. “Sometimes the name is also the same, like Dhobi, in Muslims and Hindus.”

Ali Anwar was asked why even the OBC led parties treat Muslims as monolithic.

“Because it is in their thought and concern. But it wasn’t in Ambedkar’s thought, or Gandhi’s, or Lohia’s, or Rahul Sankrityayan who was a Marxist. They agreed that Muslims like the Hindu samaj are divided into jatis.

“So why are they afraid? They have the excuse that Muslims as a community will vote for secular, social justice line parties wholesale, so it’s better to keep them monolithic rather than subdivide and suffer.

“But the difficulty is it’s not only about Muslims. Those who used to say Bahujan now say Sarvajan. They are talking of everyone from A to Z. They don’t trust their own people, only the fistful of people who are in the corridors of power. They speak to their pleasure and for their comfort and appeasement.

“It is their own ideological bankruptcy. Not learning from the BJP, and how firm it is in its own ideology. The tragedy for Pasmandas has been that all the social justice parties are afraid to give them tickets, make them ministers, move them up, so as not to upset the upper caste Muslims.

“Now look at how both Owaisi and the BJP are saying Pasmanda! Those we vote for are too afraid to take our name, and these two… Of course their hearts are different. Owaisi knows the Pasmanda won’t fall for his swindle. Earlier he would be upset by any mention of Pasmanda. Similarly the social justice parties who talk Lohia, Ambedkar, are afraid to take our name.

“But our movement is accelerating and you all have a role in it as well. We started it 25, 30 years ago and now they are beginning to understand, but feeling afraid.

“There is another reason. With Muslim society, as with Dalits when they got reservation. Dalits want an independent thinking man like Chandra Shekhar. But these people don’t like him, he’s a hard hitter, he goes for the frontal attack. Not him then.

“Likewise with Dalits, they want the weakling kind of Dalit in front. We saw it with SC seat reservation in Bihar and other states. For the upper caste Hindus their own dependents, their ploughman, their shepherd, their servant would get the ticket. So is it with Muslims. Even the BJP and the secular parties are looking for men of the broker sort, who will go to Parliament and raise their hand and vote, not talk of their own samaj. They don’t like that variety.

“This is the upper caste hegemony we talk of as Pasmandas. Now the upper castes have started saying Pasmanda, but people are beginning to understand, and I don’t think the stigma will last much longer.”

Faisal Devji said it was important to move the discussion beyond north India.

“Ashraf, Ajlaf, Arzal only has meaning in north India. Bengal is different, in western India there are tiny but wealthy and influential castes which are of the Baniya type though they’ll say they are Rajputs, and in the south it’s different entirely. So I wonder if it might be an important task to pluralise the debate on caste itself among Muslims, by looking at these other places.

“In some of them Muslims do better than in north India – which of course does badly in general compared to the rest of the country – but partly because there are different sociologies and demographies in play. So politics between Muslims and non Muslims, and among Muslims themselves, might have a different resonance in south and western India, and in other parts.

“This is crucial because Muslims from Bihar and UP are found in large numbers there as migrant labour. But also because a great deal of the funding for Muslim religious causes comes from outside north India. It can’t be sustained by the north, and hasn’t been sustainable since the early 20th century, which is why even Jinnah and the Muslim League were headquartered in Bombay.

“So whether it’s the Tablighi Jamat, whose funding comes from Gujaratis and its leadership too, or others, everyone makes the pilgrimage to Bombay, Kerala, someplace. It’s crucial for a wider understanding of ulema networks, Sufi networks, where the money comes from and to whom it goes, how it is distributed. We need to think outside north India.”

Ali Anwar concluded with an example from Andhra Pradesh.

“YSR, who is the CM and his father was CM, added some upper caste Muslims to the OBC list in the state. This is a pan India phenomenon including Bihar, that some upper castes have been added to the OBC lists. The court said no. PS Krishnan in his report took them out of the list. The court okayed it. And Owaisi opposed this. He took out protests. They burnt an effigy of PS Krishnan.”

‘Counting Caste: Breaking the Caste Census Deadlock’ was hosted by Oxford University. A discussion on majorities, minorities and invisibles with Grace Banu, Satish Deshpande, Dilip Mandal and Kanimozhi Karunanidhi is reported here, and on Hindutva’s caste issues with Bharat Patankar, Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd, Christophe Jaffrelot and Sagar Choudhary here.