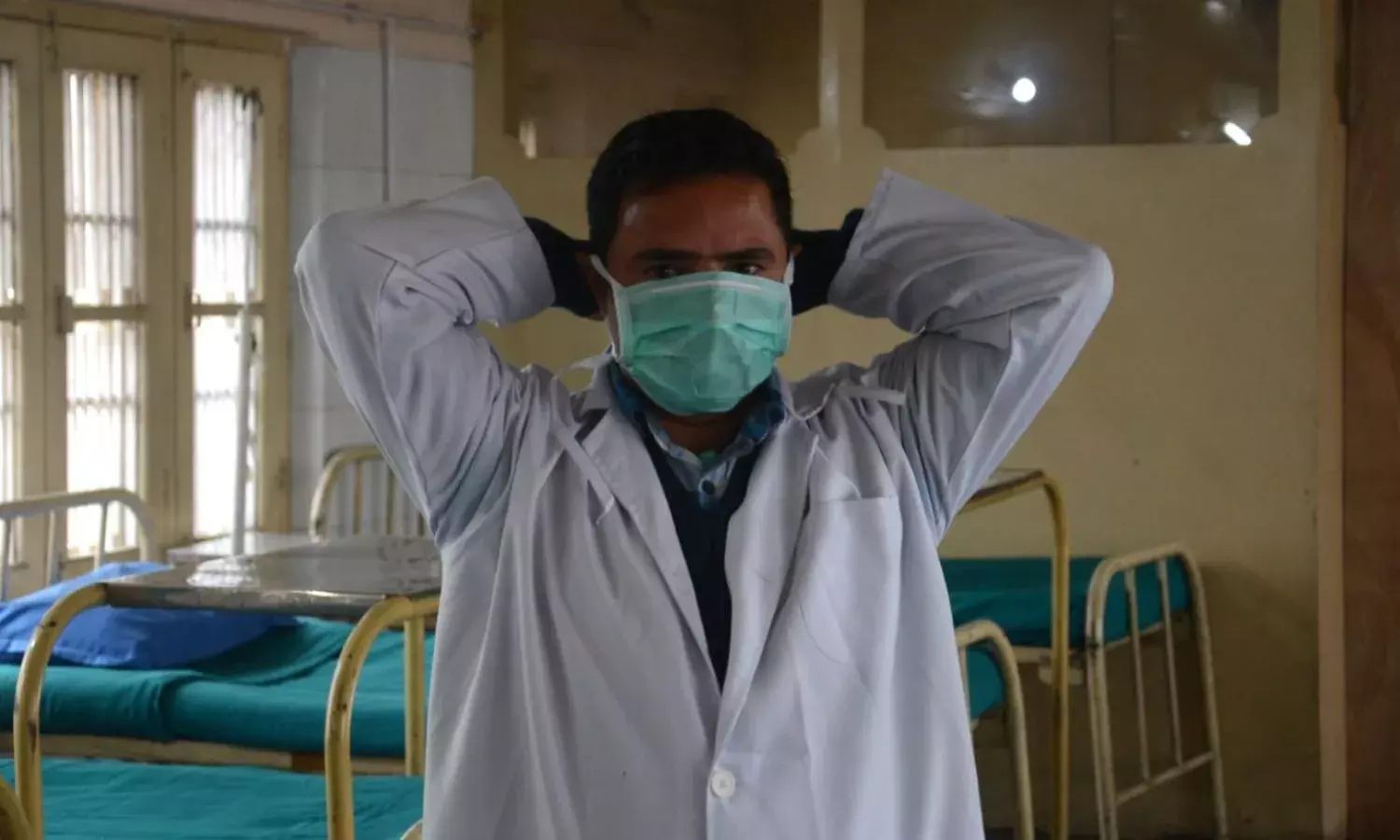

The Case for a ‘Mask Revolution’ As Hospitals Collapse

With lockdowns lifted, we are staring at a protracted journey

The initial set of WHO guidelines on masks, released on April 6, did not emphasise their use as strongly as distancing or handwashing, and limited it to a narrow set of circumstances. This implicitly discouraged community-wide masking, leaving it largely up to national governments.

These were some of the reasons given for restricting mask use: limited evidence of its benefits in healthy people, the possibility that it may lead to mask shortage for health personnel, and the likelihood that it may create a false sense of security which, in addition to improper handling of masks, could exacerbate the risk of infection.

In the initial days, the government of India chose to abide by these guidelines issued by the dominant international order of the day, issuing an advisory for the widespread use of homemade masks on April 3.

In fact, the central government did not ban the export of masks until as late as February 25, by which time COVID19 had made inroads into well over two dozen nations including India.

There has always been some way of circumventing each of the disadvantages of widespread masking posited by the WHO.

Masks, similar to distancing, can be an important population-level intervention (mainly in terms of ‘source control’) in addition to conferring individual protection.

Given that COVID19 can spread from pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic persons, universal mask use (where both the infected and healthy wear masks) becomes an apt and cost-effective strategy for slowing the epidemic, with particular relevance for places where disease distancing is difficult to maintain.

Countries like Slovakia used indirect evidence to rationalise the widespread use of masks much before the WHO released its guidelines discouraging the same. This logic, however, has been slow to penetrate the dominant international discourse in an over-enthusiastic quest for “hard” evidence.

While India did adopt public masking in April, the emphasis has been nowhere near what a crucial population-level intervention to curb the flaring pandemic should receive.

But what is particularly concerning is that this trend continues unabated despite two important developments: ‘Unlock’ or the relaxing of the lockdown, and second, the fact that we stare at a protracted journey to the peak of the pandemic.

These call for immediate reinforcement of our public masking strategy.

Lately, a flurry of studies has emerged demonstrating that universal mask use could significantly curb the ‘community spread’ of coronavirus, a stage that India has dreaded ever since the pandemic’s inception, and which is presumably already upon us.

The same evidence also compelled the WHO to somewhat relax its guidelines on public mask use.

One study showed that 75% mask compliance in the population could bring the infection’s reproductive number to below transmission level without requiring a lockdown.

Eikenberry et al noted that mass masking – even with relatively inefficient masks – could cause a meaningful reduction in community transmission.

This has immense public health implications, as even a small reduction in the numbers would mean a major reduction in the requirement of health resources like doctors, beds, ventilators.

It is an open secret that the latter is the weak underbelly of the country that is now becoming increasingly visible, as reports of patients failing to obtain hospital beds in major metropolises like Delhi keep surfacing regularly.

The Way Forward

Czechia started the slogan “Your mask protects me and my mask protects you.” Everyone viewed it as their individual contribution to curbing the pandemic. Mask non-compliance attracted a fine of CZK 10,000. Even smoking in public places was banned to prevent people removing their masks.

Similarly, Morocco provided masks at subsidised rates, and imposed a fine of 1,300 dirhams and/or a jail term of three months in case of non-compliance.

Taiwan back on February 6 started a Mask Rationing System, which allowed anyone with a national healthcare ID to buy two adult masks per week, and subsequently also ramped up production.

It is important not to be swayed into believing that all is well with our present masking strategy just by everyday sights of people wearing masks in major metropolises.

Such an impression could conceal multiple, subtle gaps which have major implications.

For example, it is not uncommon to witness instances of improperly worn masks being publicised regularly on television, and there could be a significant awareness gap in this area, despite the advisories put up on government websites, which few may access.

It is imperative to address such gaps.

Following ‘Unlock’, other than advisories on COVID-appropriate behaviors, the government has come up with little to promote universal masking with renewed vigour.

It is crucial that we move beyond advisories towards a sustained and concerted national strategy to ensure widespread mask adherence.

This has to be in keeping with both the demands of the present day and those of a protracted future course of the pandemic.

As the aforementioned country examples bring out: strong risk communication to cultivate public responsibility and accountability, ensuring an adequate and equitable supply, and appropriate regulatory provisions would form the three main pillars of the response.

A suitable mix of these can be tailored to suit regional contexts.

Particularly in public health, it is intriguing how the answers to the biggest problems lie in the simplest of interventions. It is likely that part of the answer to India’s collapsing tertiary hospitals lies in a simple ‘mask revolution’ of sorts.

Dr Apurva Jain studies public health at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. Dr Soham D.Bhaduri is a physician, health policy columnist, and chief editor of ‘The Indian Practitioner’ medical journal

Cover Photo: BASIT ZARGAR

Click on the dropdown button to translate.

Translate this page: