What Did Gandhi Eat?

‘I see death in chocolates’

Food, especially the eating or giving up of meat, has recurred in upper-caste discourse since the early days of resistance to colonialism in 19th century Bengal. Then the discussion primarily pivoted around whether Indians should consume meat to acquire physical strength like the Europeans, who had used it to subdue the Indian population, or stick to vegetarianism seen as suited to the tropical climate.

When these articles and intense discussions said “Indian” they meant Caste Hindus, many of whom were already vegetarian. The many meat-eating Indians of all religions were neither a part of these discussions, nor a subject.

If one man managed to make vegetarianism a mainstream nationalist agenda, it was Gandhi.

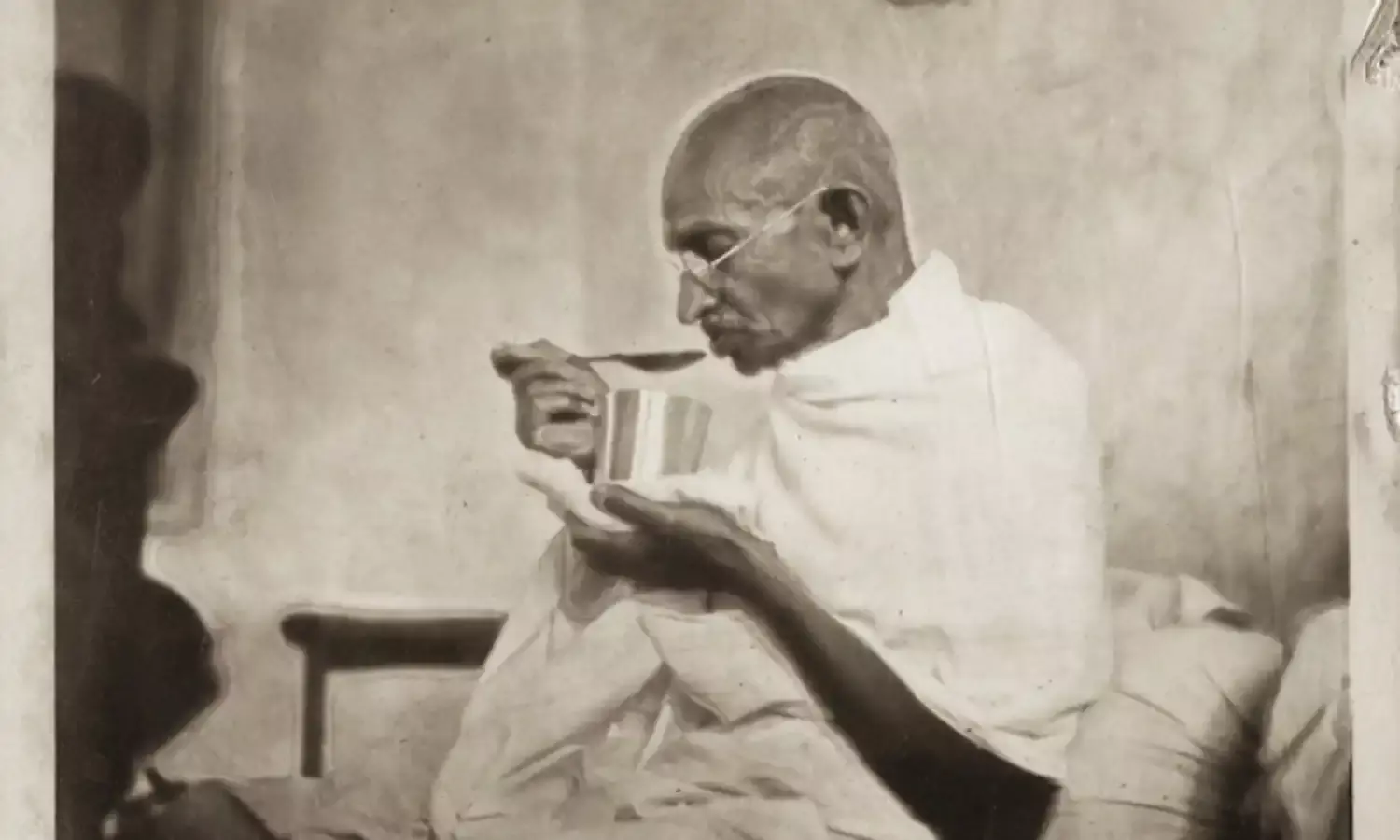

A zealous vegetarian, even vegan, Gandhi experimented so often with food and fad diets he would put our average millennial to shame. Intermittent fasting, only raw food, abstaining from salt and sugar, and veganism, you name it and he had tried it. He even perfected the production of almond milk in his ashram.

Yet not all of his whimsical experiments with food were an extension of the Caste Hindu, Vaishnav thought he internalised and has often been called out for. Much of it was political, meant to turn the conscience against the oppressive conditions of production that food entails.

Nico Slate at Carnegie-Mellon University has beautifully brought together Gandhi’s engagement with food in his book, Gandhi’s Search for the Perfect Diet: Eating with the World in Mind.

If one man put his body at the core of his politics, it was Gandhi. Be it satyagraha, fasting, non-violence, or food, depriving and disciplining his body was his primary weapon of warfare. His disciples were expected to do the same. His granddaughter is said to have advised Gandhi on her visit to Sevagram to rename it Kolagram, or pumpkin-village, so tired was the five-year old of eating pumpkins every day.

It is interesting to revisit Gandhi’s obsessive food and fairness politics in the context of the recent farm bills that have exposed Indian agricultural workers to the whims of a corporate market.

“I see death in chocolates,” Gandhi declared with characteristic bluntness. Sugar and cocoa were both grown by farmers in slave-like conditions in the colonies of Latin American and Africa, and Gandhi was no stranger to the fact. In fact, the political economy of sugar was so organised that a commodity thought of as a luxury in the late 17th century had rapidly transformed into a staple in the European diet and was then exported to other colonised markets including India.

In rejecting sugar, Gandhi was making a political statement against the conditions of labourers that facilitated this enormous industrial growth. In rejecting mill-refined salt, he questioned the colonial government’s unfair taxation of a basic commodity, leading to the Dandi march.

As we usher big businesses into mandis by the stroke of three bills, it is important to ask if we are exposing farmers to the same conditions of production that Gandhi so ferociously opposed with alternatives. As ethical consumers, shouldn’t we concern ourselves with the conditions of production?

To Gandhi, what was on his plate was defined to a great extent by what was his politics. The rejection of sugar, cocoa and salt was largely a rejection of slave labour, indentured labour and imperialism respectively. In rejecting and experimenting, he was creating alternatives that are sustainable, and resist changing the political economy in such a way that farmers have no option but to cultivate what is demanded of them.

One of the perils of ushering the corporate into the mandi is that the price corporates are willing to pay for some food will be much more than for others. This will gradually force every farmer to grow certain crops to ensure her survival, and before we know it, healthier alternatives will disappear or become much more expensive to consume.

This was precisely the case with sugar in the colonial years: healthier alternatives like jaggery and honey were effectively replaced to give us a sweetener that has almost conclusively been proven harmful.

To care about what we eat and how it is produced is, therefore, an important political lesson that we need to learn from Gandhi so many years later. We cannot possibly lead a healthy life if our sources of affordable, healthy food are compromised by a few big producers and their demands.

Unfortunately, we have increasingly come to see our bodies and lives as separate from politics and policy, limiting our interests to an occasional respite from taxes and a budget revision every now and then.

Gandhi’s experiments with food and diet thus bring us back an important lesson: to associate everyday politics and policy with our bodies, health and everyday lives.