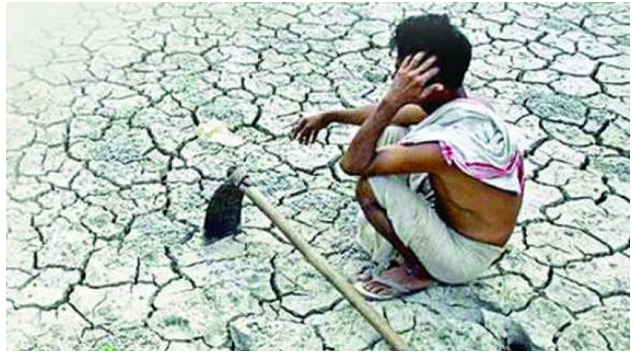

South India Reels Under Severe Drought: 'Not A Lack of Resources, Just an Absence of Political Will'

NEW DELHI: The northeast monsoon in 2016 was the worst ever over the last 140 years, according to the Indian Meteorological Department( IMD), triggering a major water crisis in South India. The absence of alternative water resources in the face of government apathy, has led to severe- widespread crop failures, rising indebtedness of farmers, and a wave of farmer suicides, particularly in Tamil Nadu, where an estimated 100 farmers killed themselves in December alone.

According to media reports, more than 144 farmers committed suicide in Tamil Nadu in the three months from October to December. While farmer suicides in Tamil Nadu are hardly unprecedented, with the state recording 606 farmer suicides in 2015 according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Unofficial figures touch different levels altogether, some even taking the tally to 1000.

The spike in suicides over late 2016 and early 2017 is being attributed to two reasons.

Firstly, the failure of two successive crops has led to a collapse of income and therefore caused much distress. The summer crop was lost to the dispute between Tamil Nadu and the neighbouring state of Karnataka over sharing waters from the Cauvery river. The winter crop was lost to the very weak Northeast monsoon in the winter months, when the state gets most of its rainfall.

Secondly, the fall in income, on top of an already precarious financial situation, led to rising debt levels. Credit was taken for the substantial input costs of farming , and with successive crop failures, the farmers struggled with debt repayment, driving many of them to take their own lives.

The southern parts of India depend heavily on the North-eastern monsoons, which comes in the months of October to December. It is particularly vital for the eastern part of the peninsula, such as Tamil Nadu and coastal Andhra Pradesh, where it contributes to almost half of the annual rainfall. It’s also important for Kerala, and interior Karnataka, where it contributes up to a fifth of the total rainfall.

The Northeast monsoon in Tamil Nadu has been deficient by close to 70%, according to the regional meteorological department. On 10 January, the then Chief Minister O Panneerselvam had already declared Tamil Nadu drought-hit based on an assessment undertaken by the state. In a memorandum to the Prime Minister, Panneerselvam declared all 32 districts of the state drought-affected, and urged the Centre to sanction Rs 39,565 crore from the National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF) for relief.

Kerala, which was already reeling from a bad South West monsoon, where it received rainfall 33% below normal, also suffered gravely from the failure of the North East monsoon. It is now all set for its hardest drought in 115 years, and the worst since the state’s formation in 1956

Karnataka is dealing with its third consecutive year of drought, with 136 of the 175 taluks in the state already drought-hit and experiencing severe drinking water crisis.

The severe drought received some belated national attention when, in March, bands of protesting Tamil farmers took to the streets of the capital and indulged in outrageous acts of protest. Among other dramatic gestures, they drank their own urine, displayed the skulls of their fellow farmers who had killed themselves, and demonstrated naked outside the Prime Ministers office, all of this to draw the attention of the Central govt to their demands-meaningful drought relief and waiver of their farm loans.

Disaster relief is primarily the responsibility of state governments, but the funds for disaster relief are mainly provided by the Centre. When the impact of the disaster is particularly high, such as in this case, it is normal practice for states to ask the Centre for additional financial and logistical support from the National Disaster Relief Fund.

In February, the Centre released Rs 3000 crores for drought and cyclone relief in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, from the National Disaster Relief Fund(NDRF). Of the total amount, Tamil Nadu received Rs 1,712 crore, while Rs 1,235 crore went to Karnataka. Following the release of Central funds, the Tamil Nadu government allocated Rs 2,247 crores to provide relief to 32 lakh farmers who had suffered huge losses due to crop failure.

However, the quantum of relief was deemed to be grossly insufficient by the protesting Tamil farmers who had been demanding a more substantial drought relief package, of Rs 40,000 crore, from the Centre. In fact, this was the quantum demanded by the then CM Panneerselvam when he wrote to the Prime Minister in January. Their other demands- farm loan waiver and setting up of Cauvery Management Board- were also not met by the Centre, which prompted them to pour into the capital in March and start their dramatic 40 days protest.

While the Tamil farmers have ended their protest in Delhi after assurances over their demands from Central and State government, many Tamil farmers remain deeply unhappy over the relief measures. A recent Economic Times report quoted farmers claiming that the relief amount they received was a pittance and many times lower than the input cost. For instance, for paddy, the state government promised Rs 5,465 an acre, while the farmers claimed the input cost of irrigating, ploughing, seeds, fertilizers, and harvesting amounted to Rs 30000 an acre.

India has been increasingly affected by droughts over the past few years. The country suffered two back-to-back droughts in 2014 and 2015 following the failure of the annual south-west monsoon, a rare phenomenon that had occurred only four times in the past 115 years. Even last year, prior to the onset of the monsoons, which were normal, water shortages affected an estimated 330 million people in 10 states.

The Supreme Court responded to the grim situation of last year by directing the Centre to frame a National Drought policy that would prescribe a standard methodology and time-frame for declaring drought. The Court further called for the use of modern technology for early determination of drought, and a national plan for “prevention, preparedness and mitigation” of drought.

“The problem is not lack of resources or capability, but the lack of will,” the bench observed, criticising the state governments for their ‘ostrich-like attitude’ and calling on the Central government for ‘a far more proactive and nuanced response’, instead of just delegating all responsibility to the states.

However, few lessons seem to have been learnt from last year, by governments at both the state and the Central level, and the Supreme Court directions have been virtually ignored. A recent report by three international water policy experts claims India is facing its worst water crisis in generations.

“Centuries of mismanagement, political and institutional incompetence, indifference at central, state and municipal levels, a steadily increasing population, a rapidly mushrooming middle class demanding an increasingly protein-rich diet that requires significantly more water to produce—together, these are leading the country towards disaster”, the report ominously remarked.

While many parts of the world receive sparse rainfall, such as Israel and California, it does not lead to droughts and rural suicides in most places due to an efficient infrastructure of water reserve and usage. In India, however, successive governments have failed to put in place a comparable infrastructure, and 54% of the net sown area remains unirrigated and hence dependent on the seasonal monsoons, which are increasingly erratic.

Climate change and continuing environment degradation is taking an already bad situation to catastrophic levels. “The sand mafia colludes with local politicians and illegally removes sand from the riverbed, which prevents water from percolating into underground aquifers”, Nirmala G, a renowned environment journalist from Kerala, told the Citizen.

“It’s futile to simply blame bad monsoons for all the farmer distress”, she remarked, emphasising particularly the need to popularise simple techniques with far reaching benefits, such as rain water harvesting and drip irrigation. Environmentalists, water policy experts and farmer unions all hope that the politicians wake up to this increasingly gloomy situation instead of taking cosmetic, temporary and reactive measures.