Budget 2017. What to Expect?

NEW DELHI: Having dug himself into a hole with demonetization, Prime Minister Narendra Modi needs to make a huge effort to climb out of it. But there are severe limitations on what he can do.

The first budget was the great opportunity for road reversal by dealing with burgeoning unmerited subsidies, huge tax-giveaways, unproductive industrial investments and making the investments needed building and modernizing infrastructure, creating 12 million jobs a year and reforming governing structures.

That was the great opportunity for good economics. He missed it. Now it is time for what passes off as good politics. Good politics means winning votes and in India that is usually by more unaffordable populism.

Unfortunately the government is backed up against a wall. Most economists and educated observers in India and abroad have concluded that the big axe of demonetization wielded with savage force and fury was entirely ill advised and ineptly implemented. The IMF has reduced 2016-17 growth estimates by 1%, suggesting a loss of Rs.1.5 L crores. Others see bigger losses over a longer period.

The well regarded Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) has not only pared down real GDP growth is year to 6%, but has opined: “We now expect this growth trajectory to shift down to about 6% per annum for the next five years (up to 2020-21). The economy is unlikely to achieve a growth of 7% any time during the coming five years.”

This is even more significant considering that a few months ago the CMIE was very optimistic about India’s economic prospects and had forecast growth to be between 7.5 -8%. In effect the CMIE is cut down its optimism by almost 2% and expects the chill winds to blow for the next half a decade or so. That would be a huge blow.

The blame is all pointed at Narendra Modi and he is under pressure, not only by a reviving opposition but also by the more conservative forces within the secretive and conspiratorial RSS. The election results in the three northern Indian states of Uttar Pradesh, Uttaranchal and Punjab will have a huge bearing on Narendra Modi’s political future.

The trends seem quite obvious in Punjab but being saddled with a burdensome ally affords Modi a cushion against the barbs. Uttaranchal is too small to matter. The make or break state is Uttar Pradesh. The BJP won 72 out of its 80 parliament seats and this hugely expanded its parliamentary majority despite a 31% mandate.

Political majorities easily change in UP and this must be very worrisome to Narendra Modi? Adding to his concerns most definitely will be the aura of development and youth constituency that Akhilesh Yadav seems to be fast acquiring. What was till not long ago expected to be a cakewalk has now become a steep climb. Besides Modi has a record on not faring well in head to head contests in state elections against charismatic regional chieftains, as in Delhi and Bihar. These states enjoy a certain co-sanguinity with UP and they tend to be similarly politically predictable.

What many people do not seem to realize is that almost 96% of the budget comes pre-set because of existing commitments. Allocations for interest, defence, salaries, and transfers to the states cannot be touched. Tax rates can be tinkered with but cannot be lowered unless a case can be made for higher realizations. As it is India’s Tax/GDP ratio is not very encouraging.

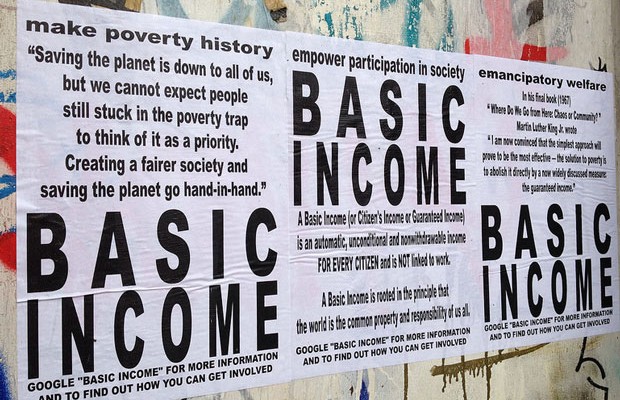

Even so the power of incumbency is still a huge advantage with Prime Minister Modi. The Brahmasastra for the season now must almost certainly be the Universal Basic Income (UBI) scheme now being touted by many new age economists as an idea whose time has come. The CEA, Arvind Subramaniam, recently argued for it. Even the Vice Chairman of the Niti Ayog, Arvind Panagariya while opposing it seemed to be doing so for perceived budgetary constraints rather than for ideological reasons.

The UBI entails the direct transfer of a certain amount of cash every month or week or even quarterly to every citizen. The figure bandied about is a UBI of Rs.1000 pm. To the average Indian family of five, this will amount to a good Rs.5000 pm. This will more than comfortably cover the monthly food bill and still leave a bit. But the cost of this will be over Rs.15.6L crores a year. That is over 10% of GDP.

The subsidy bill for 2016-17 the subsidy bill on food, petroleum and fertilizers was estimated at Rs 2,31,781.61 crore. This was held down to about the previous years allocation mostly due to the falling oil prices. The petroleum subsidy was reduced to Rs 26,947 crore for 2016-17. Of this Rs 19,802.79 crore was earmarked for LPG subsidy and the rest is for kerosene. This subsidy varies with oil prices and was not long ago over Rs.1.30L crores. But the bad news is global oil prices are on the rise again due to renewed cartelization by OPEC and Russia.

Besides these subsidies are political holy cows. Farmers, particularly in the irrigation intensive Punjab and UP who are major users of fertilizers will take unkindly to any reduction. Cutting down LPG subsidies will alienate the subsidy fattened urban middle classes.

Food subsidies are in reality subsidies to the big farm producers in Punjab and western UP because of minimum support prices (MSP), which increasingly are above market prices. Distribution of food grains under the PDS is just a fig leaf to cover high prices to big farmers. Thus politically speaking, touching these subsidies will be counter productive and may neutralize any political benefits accruing out of UBI.

But the PM could very well resort to a basic income to every person below the poverty line. This will entail a subsidy of about Rs.3L crores a year. It’s still a big bill. But desperate measures are a big temptation in desperate times.