The Girl With The Face-Tattoo

RANJU DODUM

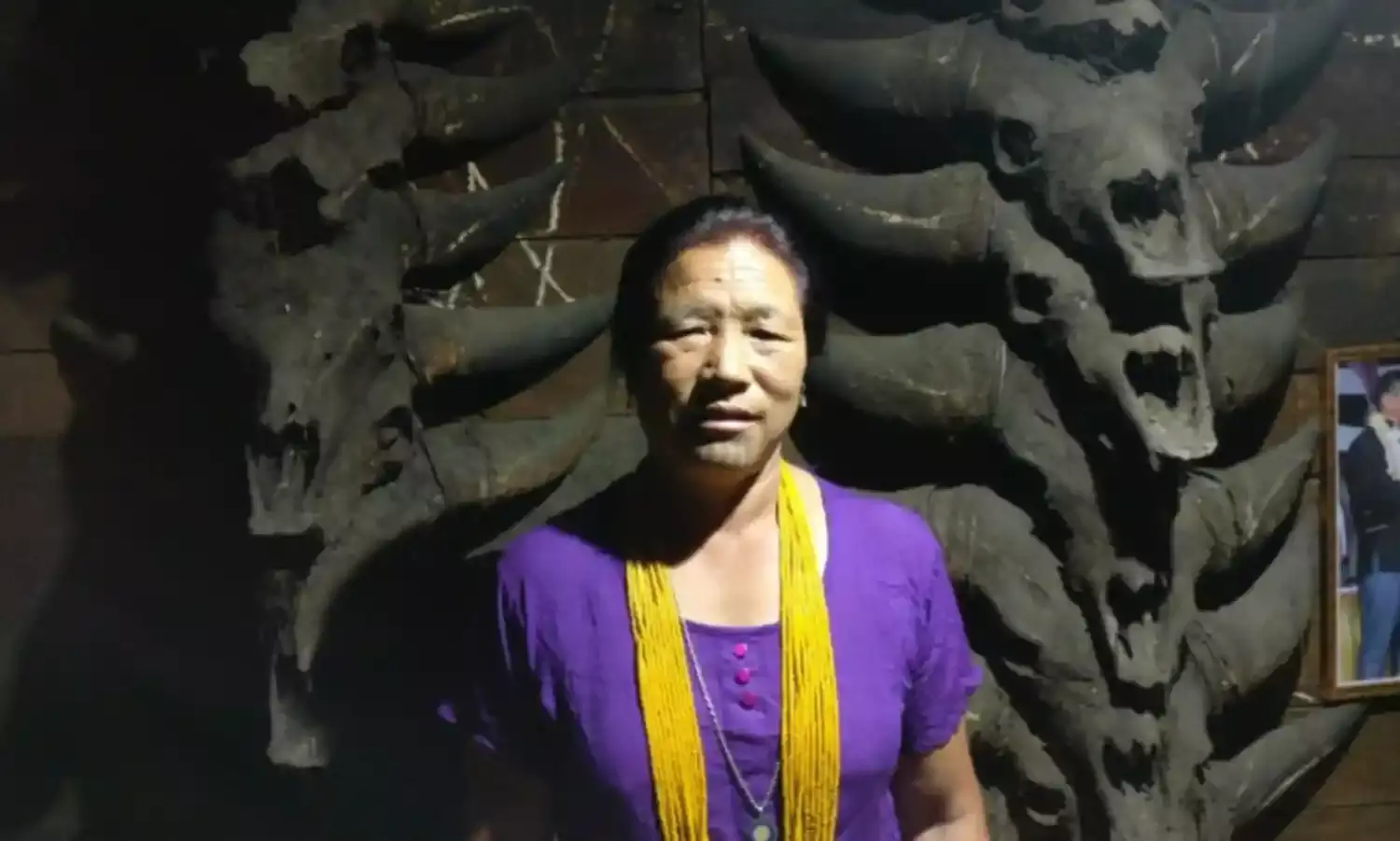

ITANAGAR: In the kitchen of the home-stay that she and her husband run, Narang Yamyang said that the woman who tattooed her face refused to continue if she showed any signs of experiencing pain. Left with no choice, she remained motionless through the entire process.

Until the early 1970s, it was common practice for women of the Apatani tribe of Ziro Valley in Arunachal Pradesh to get their faces tattooed and sport nose-plugs. The process was conducted in the winter to quicken the drying process, was often long and always painful.

The tattoos of a woman, called tiipe in the Apatani language, usually run from the top of the forehead to the tip of the nose, complemented by five strips starting from the edge of the bottom lip to the end of the chin. Some also pierced their noses and over the course of time larger nose-plugs made of cane called yaping huto would be placed. The ink that was used is basically soot (called chinyu) collected from the bottom of heavily-used cooking utensils.

And no fancy tattoo needles here; what was used as a ‘needle’ was made by tying together a bunch of three-headed thorns called iimo-tre. A small stick hammer called empiia yakho helped produce the necessary pressure to pierce the skin and hammer in the ink.

Once a defining character of the Apatani people, the practice was banned by a tribal youth organisation in 1972; the penalty for which was almost equivalent to the price of an adult mithun at that time.

Yamyang said she got herself tattooed sometime after that but was not fined because her father had passed away and the implementing organisation spared her the penalty.

Having been socially abolished over four decades back, getting a glimpse of the tattooed women of Ziro is becoming a rare sight. Everyone who sports them is at least over 50 years old. It has completely disappeared among young Apatani women.

Tattooing has existed in different cultures throughout the world. From the Polynesians to the yantra tattoos of the Tai people, tattoos have been always part of human civilisation and have survived till the 21st century with varying degrees of prevalence. Closer home, tattooing was common among the Baiga people of Chota Nagpur Plateau.

In the Northeast, among the Naga tribes, it was a matter of pride for men to sport certain tattoos as it was an indicator of their martial skills. Unlike most modern-day tattoos, in the lives of indigenous communities, tattoos usually signified a rite of passage and a coming age for young men and women. So why did the Apatani women get them done?

At the very outset, it is important to note that it is not just the women but also the men who once got facial tattoos made, although the men only drew one thick line down the middle of their chin. Regardless, both men and women only got tattooed after they had reached puberty. It is when trying to unearth the reason why the practice started is where things get interesting.

Images of smiling women with blue-hued tattoos and nose-plugs abound the internet. The most repeated (and most believed) story of why the women had them made was because the Apatani women were so beautiful that the men of the ‘neighbouring tribe’ would repeatedly raid their villages and kidnap them. While this does not explain why the men got tattoos, many people, including those of the aforementioned ‘neighbouring tribe’, still believe there is credence to the story.

Yamyang’s husband, Tam, said that the story probably began once young Apatani people began to move out of the Valley and felt “awkward” when people, especially the plainsmen of Assam, would stare at them.

In the absence of any documented evidence of mass kidnappings of Apatani women ever having had taken place, the story is apocryphal at best and what anthropologist may describe as a type of cultural cringe where people are made to feel that certain aspects of their cultural practices are inferior and must be discarded.

Tam said that earlier it was essential for an Apatani to have a tattoo as it was a mark of their identity. “People would not even get married if their faces were not tattooed in the old days,” he said.

There are other explanations offered by the older Apatanis and the women who have the tattoos.

Tilling Rilung, an agriculturalist and wife of a gaon bura (village headman), said that the tattoos were made to distinguish between the Apatani people and the neighbouring Nyishis, indicating that it acted as a marker of tribal identity.

Like most other women who spoke of their experiences, Rilung too had to be held down on the floor when she was getting her tattoo made.

Duyu Dinsung is another woman who said it was a painful experience and resonated Rilung’s explanation that they were made so as to distinguish between the Apatani and Nyishi people.

Hage Tado Nanya, a progressive farmer and a pioneering face of women’s engagement in Apatani society who also happens to be the reigning Mrs Arunachal, said that she was among one of the last batches of girls who got tattooed after the ban was imposed.

As with those who actually had had their faces tattooed, she too dismissed the kidnapping story and even claimed that the practice existed among the Apatani before they migrated to present-day Ziro centuries ago. In fact, she claims that the seeds of the iimo-tre plant were brought during the migration period.

The story behind the Apatani tattoo may have gotten lost in recent years and replaced with another. While there is no consensus over the origins of the practice, what everyone- tattooed or not- does agree on is that it is good that the practice has stopped.