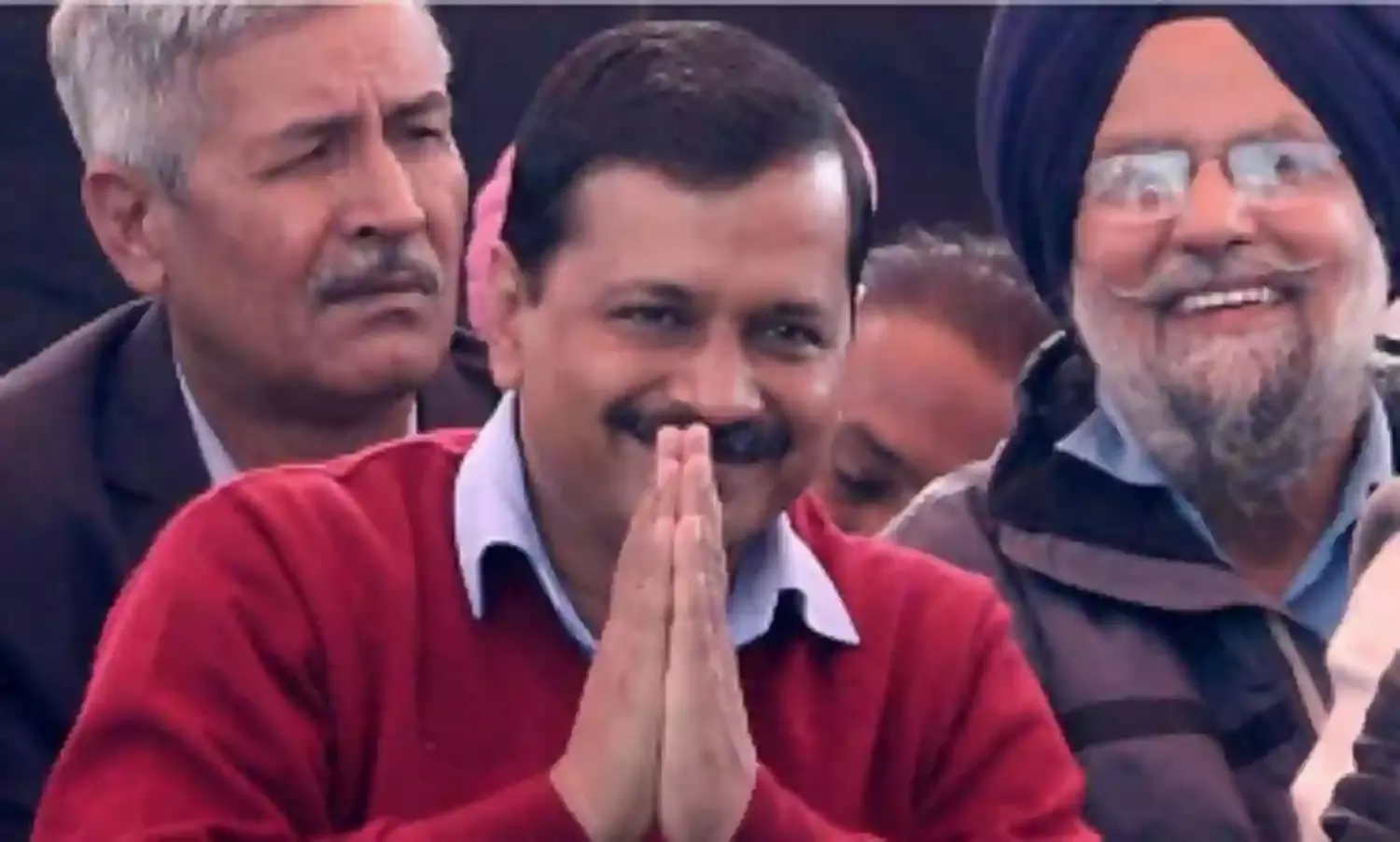

Kejriwal Should Now Apologise to the Nation

Kejriwal Should Now Apologise to the Nation

Arvind Kejriwal’s apologies are the talk of the town. He is currently on a spree apologising to his bitter political rivals, which include Bikram Singh Majithia, Nitin Gadkari, Kapil Sibal, and Arun Jaitley. At this rate, he would end up apologising at least 16 times, making him the first politician in India to do so. It might also be worth checking the Guinness Book of world records.

Kejriwal, through his supporters and lawyers, has claimed he wants to focus on governance, which these various defamation cases distract him from. Further, the time and money involved in it is something the Aam Aadmi Party cannot afford.

It is otherwise a valid argument. Criminal defamation case is rampantly used as a tool by the mighty and powerful to shut up journalists and activists. Cases go on forever and little comes out of it. Even the British, who introduced this law in India, have rescinded it back home, while we still continue with it. However, an ordinary activist wanting to get out of a criminal defamation case is different from an anti-corruption crusader chickening out and apologising to his political rivals, since it is the precise premise on which he became the Chief Minister of Delhi.

Kejriwal’s political career began through the anti corruption movement led by Anna Hazare in 2011. It had a pivotal role in bringing down the UPA-2 government. Anna might be the face of the movement, but Kejriwal pulled most of the strings. He even took on big industrialists like Ambani, and most powerful politicians like Narendra Modi. Kejriwal appealed to the electorate as a man who was taking on the rotten system, and the electorate trusted him, not once, but twice.

How will Kejriwal face the same electorate after apologising to the same people he claimed to take on? In each of the press conference, or speech, Kejriwal claimed to be making statements based on proof. If the electorate turns around and asks if it was a cheap stunt to win elections, would it be an unfair question? Having offered no concrete explanation himself, he seems to be expecting the people to accept his decisions without asking any questions. A bit similar to, you know who.

To say Kejriwal wasn’t aware of the consequences of taking on big industrialists and politicians would be unbelievable. A Magsaysay award winner, having spent most of his life in the IRS, has a better understanding of law than that. After all, the criminal defamation case is not new. Maybe he underestimated the quantity of such suits. He has probably realised there is a difference between agitating at Ramlila Maidan and actually taking on the corrupt.

Some might interpret it as a concession of defeat, others might say he has become pragmatic. Some might well be reminded of GR Khairnar, who had promised to provide truckload of evidence against Sharad Pawar. But the common citizen would certainly feel let down, and opposition parties would be celebrating.

However, these developments revive the debate of the kind of leader Kejriwal is. The debate that ensued after what happened to Prashant Bhushan and Yogendra Yadav. In his book, Mayank Gandhi has counted several examples of Kejriwal’s autocracy. More importantly, Kejriwal doesn’t seem there is anything wrong with his style. Before apologising to Majithia, he did not even consult the top leadership in Punjab. AAP MP Bhagwant Mann resigned from the party after his apology. In fact, Majithia’s case is extremely serious. AAP had made his links to drug trade an election issue in Punjab, and after the apology, his local unit is left red faced.

The history of anti-corruption movements in India is not encouraging. Movements start on a promising note hitting the right chords, but then dissipate for various reasons. What has happened with Kejriwal is not new. For now, after he is done with all the apologies, he should issue one to the people of India for misleading them into believing in him. That would be a fitting end to the whole saga.