India As Lynchistan, Frightening and Disheartening

Back to the basics

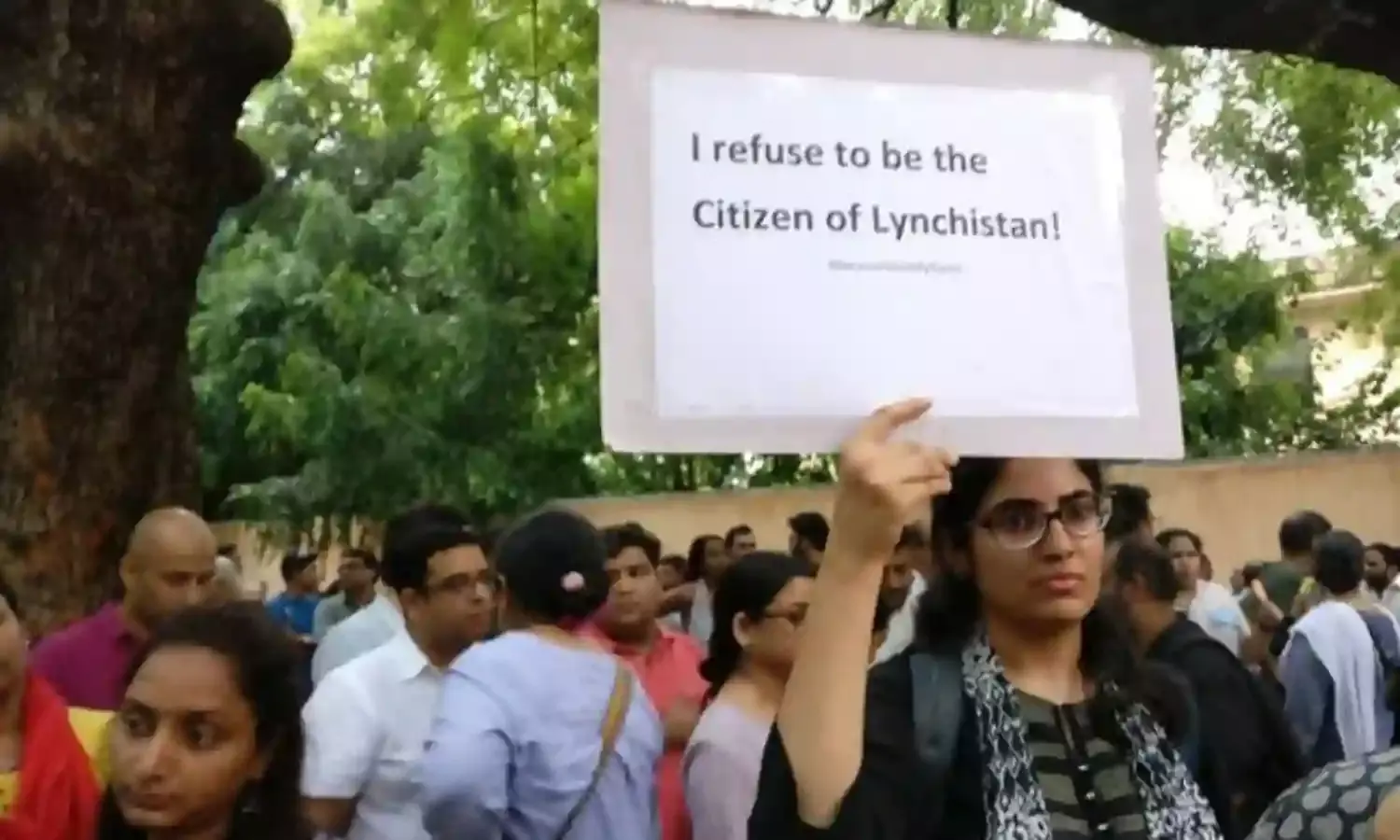

Mob lynching has emerged as a formidable threat to the image of India as a civilised country. India has truly become Lynchistan, rather than Hindustan, as some protagonists of the Hindutva cause would like it to be.

Suspected cow smugglers, child lifters, black magic practitioners, and innocent, law-abiding people have become the victims of this mindless violence. It is mobocracy in action.

This changeover of India in recent months has been frightening. But the institutional and societal response so far to this grave challenge is disheartening.

The Twitter war between the Congress and the BJP showed the extent to which public life has been muddied. The Congress party has asked for an enquiry into mob lynchings by a sitting judge of the Supreme Court. The government has responded the way it is used to, wherever states are concerned, by appointing a committee under the union home secretary and appointing a group of ministers to deliberate on the issues.

It has refreshed the country’s memory by reiterating that ‘police’ and ‘public order’ are state subjects, and that the central government’s role is restricted to issuing advisories to state governments, which it has done. Appeals to the nation’s conscience could have been made by the prime minister speaking authoritatively on the subject at the earliest opportunity.

But Prime Minister Modi, so eloquent otherwise, did not find it necessary to condemn the repeated incidents of lynching until several weeks had elapsed, giving the wrong impression about where the Government of India stood on the subject. It was qually shocking to see a central minister felicitating the accused in a lynching case by garlanding them when they were granted bail by the courts.

The response of the state governments concerned has been equally casual and lackadaisical. The Supreme Court has condemned the spate of lynchings as “horrendous acts of mobocracy”, lamenting also the apathy of bystanders, mute spectators, police inertia and grandstanding on social media by the perpetrators of these crimes.

The Supreme Court has suggested that the central government issue a directive to state governments under Article 256 of the Constitution. The Court also suggests that a separate law be enacted to create a deterrent against the tendency to take the law into one’s hand.

Let us deal first with the question of issuing a directive to state governments under Article 256. This article which deals with the obligations of states and the Union lays down that “the executive power of every state shall be so exercised as to ensure compliance with the laws made by Parliament and any existing laws which apply in that state, and the executive power of the Union shall extend to the giving of such directions to a state as may appear to the Government of India to be necessary for that purpose.”

I seriously doubt whether the central government is competent to give any directive under this article to the states, on a subject which clearly falls in the ‘state list’ in the Constitution. The states will consider it as going against the principles of federalism, which is now a favourite hobby-horse of all opposition parties.

It is also important to note that a directive can be effective only when its breach can lead to stringent penal action. The only action which can be taken against a state government is to treat this as a failure of the Constitutional machinery and to impose President’s rule. But, considering the composition of Parliament, this is clearly not feasible as such action is unlikely to be approved by Parliament.

Considering the fact that almost all states, except for a few such as Punjab, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal are ruled by the same party which is in power at the Centre, it is most unlikely that the central government will be prepared to impose President’s rule in any of these states for breach of the directive. Any such action against state governments ruled by the opposition parties is bound to be branded as political vendetta. Further, any such action is bound to be challenged in the Supreme Court and I have grave doubts that it will be upheld by the court.

Is a new law an answer to the problem? Let us await the recommendations of the Ministry of Home Affairs – but what is our experience so far? There are literally hundreds of laws on the statute books. The question is one of making use of the laws and taking action.

The main instrument for this purpose is the police, which has become totally ineffective by its blatant politicisation and communalisation. This is evident from the fact that even the directions issued by the highest court in the land in 2006 on restructuring police organisations at the Centre and in the states have remained unimplemented, though over a decade has elapsed.

It has made no difference which political party has been in power. There is no political will to reform the police. On taking the reins in 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared that his government would strive for “less government and more governance.” I had expected police reforms to be of highest priority in any such programme. But, these hopes have been belied.

The response of Rajasthan police in the recent lynching episode is a case in point. As I brought out in my book, Secularism – India at a Crossroads, the Uttar Pradesh Provincial Armed Constabulary is known to have been communally oriented for a long time, and it had also come under adverse notice during the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

The observations of L.K. Advani in his autobiography, My Country, My Life, are also highly disturbing. He has written that when he was returning to Lucknow on December 6, 1992, after the demolition of the Masjid, a senior UP police officer walked up to him and said, “Advaniji, kuch bacha to nahin na? Bilkul saaf kar diya na?” (I hope nothing is surviving and that it has been totally razed to the ground?)

Advani has cited this as evidence of public enthusiasm for demolition of the Masjid, but to me it conveys the pernicious communal mindset of the police. The Muzzafarpur riots in the 1980s and the police’s role therein is still keeping horrific memories alive. In cases of mob lynching, another disturbing aspect of police functioning can hardly be overlooked. Demands for entrusting the investigation of cases to police of other states are a significant pointer to the steeply declining credibility and dented image of the police.

There are also matters such as misuse of state governments’ power to withdraw of cases, which has diluted the deterrent effects of the penal provisions of law. Such provisions need to be amended to curtail the discretion of state governments.

During the hearing of the question of dealing with the lynching cases, it was stated on behalf of the government that responsibility needs to be fixed on district officers for any lapses in such cases. There is nothing new in this suggestion. The main question is how to deal with the political aspects of these cases. It is time some out-of-the-box thinking was done to deal with this aspect.

MLAs and MPs are public servants and derive concomitant benefits such as frequent upward revision of salaries, allowances, pension, medical facilities and so on. There is no reason why they should not be held responsible and accountable for any acts of mob lynching in their constituencies.

For, as seen since Independence, there are severe limits on what officers can do when politics enters the picture. It is only by holding the elected representatives responsible, as public servants, that major issues in public life can be addressed.

Finally, the nefarious role of social media in spreading fake news, propagating rumours and creating panic has been primarily responsible for mob violence and lynching. But there is a reluctance to address these issues, due to misplaced concerns about safeguarding individuals’ right to privacy.

Reasonable restrictions on such rights are inevitable in the larger public interest and must be enforced. A surveillance machinery for this purpose must be put in place by the government without delay. All efforts must be made to eradicate the blot of mob lynchings on India’s image.

(Madhav Godbole is a former home secretary and secretary, justice, to the Government of India.)