JP, Democracy and Revolution

The call for total revolution should be seen as a call to overhaul the system

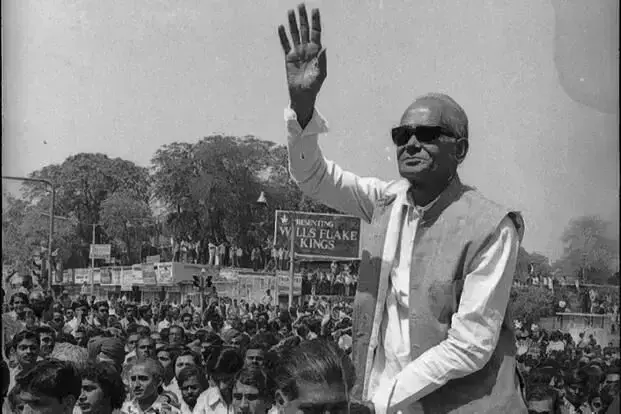

JP was the only thinker, and power-averse mass leader after Gandhiji in independent India. He started his political and ideological journey concurrently. Some observers hold that if one followed JP’s ideological journey, one would ultimately complete the whole cycle of political and social ideologies and thoughts which confronted the country during the 20th century, and which shaped the destiny of the new, modern India.

All JP's concerns and efforts to pursue his own kind of politics for strengthening people's power in India finally culminated in Bodh Gaya on April 19, 1954, where he announced a complete withdrawal from party politics, and embraced Vinoba Bhave's Sarvoday as a ‘jeevandani’, or one who had donated his whole life for the cause and purpose of the Sarvoday movement.

Search for Alternative Economic and Political System

There is no doubt that the Bhoodan movement gained momentum and attained new heights after JP joined hands with Saint Vinoba. The movement was based on the ancient ideal and practice of ‘daanam samvibhagam’ (daan or giving for equitable distribution), which required a change of heart among the affluent, more specifically the landowners, in favour of the poor and landless. No scuffle, no acrimony. Those were the days when it appeared that this peaceful, non-violent revolution would indeed change the fate of India.

Many observers consider JP’s long twenty-year association with Sarvoday not very worthy politically, and some even hold the view that it was a waste, but if one seriously analyses the events and JP's responses thereon, and his role in this period, it will be amply clear that JP's status as a statesman not only remained intact but also acquired an international stature, during the period of his ‘sanyaas’ from active politics.

JP acquired the position of a ‘one-man opposition'. He would speak on behalf of the nation on various vexed issues confronting the country, whether the question of Tibet whose sovereignty he wanted protected, or Kashmir for which he suggested a resolution within the framework of the Indian Constitution, but by ensuring the participation of local leaders, or Nagaland where his peace mission ultimately met with success after relentless efforts, or Aksai Chin, for which he suggested that the area controlled by China, where it had illegally constructed a road, should be handed over to it on lease, so that the legal right of India to the land could be protected, or the North East Frontier Agency, which he was the first person to reach after 1962 war, establishing Shanti Sena centres in the remote areas, or Chambal where he was instrumental in securing peace after three hundred years of violence, when more than six hundred ‘Bagis’ laid down their arms and surrendered before him.

JP’s search for a true and real democracy prompted him towards far deeper analysis, of contemporary practices elsewhere in the world, and of ancient Indian practices and beliefs concerning local government, in the form of panchayats, besides the role of the state (Rajdharm) as envisaged by the shastras.

JP did not hesitate to look at the ancient social and political systems of India and took inspiration from their institutions and working, to correct the faults of our present system. He had the courage and capacity to look far ahead of his time and far back into history. In 1959 he came out with an alternative model of democratic governance, in ‘A Plea for the Reconstruction of Indian Polity’, which one could say was based on communitarian theory.

In this famous thesis JP also talks about a community-economy, which is neither exploitative nor competitive. It is based on cooperation and participation and tries to be self-reliant as far as possible. It posits a ladderlike hierarchy: the primary community, then the regional, provincial, national and international. In fact, such an economy would be compatible with the delegated and decentralised form of governance. This was but natural as JP was trying to create institutions and evolve systems as per Sarvoday ideology.

On the other hand, the period in question witnessed a gradual decline in democratic traditions and values, especially on the part of the government and ruling party. The freedom struggle had been fought on the basis of liberal and democratic values, but in just twenty-five years these values were eroding, at the level of the state and in the general public sphere.

Although JP gave everything to Sarvoday, the movement was at a halt till the end of the sixties. The time was approaching when JP was to lead the country once again; a very rare opportunity for a leader to lead and guide his peoples for a second time in his lifetime.

Democracy and Revolution

By now JP had shown publicly his concern for growing authoritarianism in the country, even as the common man suffered under price rise and rampant corruption in public offices. All types of unemployment were growing and the education system was not capable of meeting the requirements of the youth. A kind of overhaul was required to put things in place.

It was a matter of chance or destiny that JP led the agitation of students and youth against price rise, corruption, the ineffective education system, and growing unemployment. The agitation began in Bihar on March 18, 1974, and witnessed much violence, met as it was with brutal suppression by the government.

Perhaps because of this suppression, JP decided to lead the agitation when the youth leaders requested him to guide them. Under his leadership, the student agitation soon became the Sampoorn Kranti Andolan, after JP’s call for Total Revolution on June 5, 1974.

This was new and unexpected. It is important to note that since independence, calls for revolution had been made only by extreme left outfits, first in Telangana and then in Naxalbari. It was indeed an astonishing political event for the call for revolution to be given by a Gandhian, and a Sarvoday leader.

What we mean by the word ‘revolution’ has never been part of our civilisational experience. Ours is a very old civilisation, and when the now-developed countries were merely nomadic, many an institution of the civilised world already existed here. The climate, the lively rivers and the fertile soil of our land made human life flourish, but at the same time the demographic realities were changing.

It is amazing that despite the existence of institutions like caste, Indian society, at first sight quite intact and unchangeable, has in truth ever been changing. The emergence of new castes and classes has always taken place, in almost every era, all of them looking and striving for an adjustment with the prevailing caste system.

The pluralist structure of Indian society became possible because of a continuous social process, and what we call cultural assimilation, identifies it. This process of assimilation has protected us from some of the extremes and excesses that people had to face elsewhere, like theocratic states, restrictions on the freedom of expression, the king's ownership of land, and totalitarianism of any kind. It is not the objective here to declare the Indian society and political system to be faultless; rather it is being indicated that the values and the ground realities of western society have been quite different from those of India.

This may be the reason why there has hardly been any urgency on the part of the general masses for a ‘sudden’ phenomenal change in the system, so a peace-worshipper's call for total revolution looked amazing. During an interview with Brahmanand, JP opined, ‘Sarvoday will be trying to change the hearts of affluent people, and make them feel their responsibility towards their poor brothers. I took up this path, but found that it had very little impact on the situation. So I thought I should suggest that the deprived people be organised and emerge strong. Even if they cannot fight the rich people they must demand their rights.’

How to bring about desired change? At one point JP makes the following reply: ‘It was to find an answer to this question that I turned from Marxism, to democratic socialism, and then to Sarvoday… I have come to the conclusion that the answer to this question cannot be found within the periphery of a single ideology, howsoever fundamental or original it may sound.’

We can infer that, while calling for a change, JP was not tied up with a readymade ideology, although his ideological journey had been a long one. Perhaps this was the reason he did not call for revolution, but ‘total revolution’. He considered all earlier revolutions, incomplete. Another important thing to keep in mind is that all prior revolutions had been made possible against totalitarian regimes. But here, JP had a parliamentary democracy, apart from the largely peaceful legacy of the freedom movement, and the rich and pervasive social and cultural values of India.

JP did not use the prefix ‘total’ casually; it meant a lot to him. All those revolutions of the past had been incomplete in his views. One totalitarian regime was replaced by another with a different brand. JP had experienced the fact and realised that the genuine interest of any individual or class could not go against the genuine interests of any other individual or class. Those revolutions remained incomplete as the common man or woman, who had made sacrifices in the name of revolution, remained powerless. They were not even free to speak their mind. It was remarkable also about those revolutions that once the seat of power was captured, the revolution was over. If any activity remained, it was only to curb the ‘counter-revolutionary’ or ‘reactionary’ forces.

In total revolution, the means had to be pure, which is to say it had to be peaceful. Deprived and downtrodden people will organise themselves and will rise against exploitation and injustice. They will take the help and support of the institutions and instruments of democracy. They will use democratic means to enjoy more democracy. There will be no separation between freedom and equality. They will attain equality to enjoy freedom and use freedom (democratic) to attain equality. And, both freedom (i.e. liberty) and equality would be meaningless in the absence of fraternity.

Thus, JP wants the radical use of parliamentary democracy and freedom of speech for revolution. He wants to save democracy at any cost, not only for the sake of freedom but also because through democracy the path of revolution would become facile and accessible. We can consider the following points to understand his concept of total revolution:

. Revolution should not be confined to economic aspects alone.

. Political, economic, social and cultural aspects should also be touched.

. Change should be total and fundamental.

. The revolution should be brought from bottom to top; the people should be at the helm, not the state, whose role would be supportive, not instructive.

. People should organise themselves on a non-party basis.

. Revolutionary forces should seek support from friendly governments.

. Powers of vested interest should be fought vehemently.

. The youth should be the vanguard of the change, by and large. People's power and youth power should complement each other.

. Revolution involves a continuous and sustained process of change.

Dada Dharmadhikari, a veteran thinker and Sarvoday leader, rightly remarked, ‘There was a revolution in this country under the leadership of Jayprakash. Revolution, because it was never expected that the background for revolution could be created within a parliamentary system. That the ground for revolution could be prepared through parliamentary democracy – this had never been thought of before anywhere in the world.’

The continuity (saatatya) aspect of the total revolution requires some elaboration. It was suggested earlier that Indian society and civilisation have the unique quality of making adjustments with new realities. It is a kind of self-processing or self purification (aatmashodhan), and it is because of this that we are still a running civilisation, while the other old civilisations of Rome, Mesopotamia and Egypt have left hardly a trace of themselves.

One of the bases of dharma has been the ‘sutra’ that ‘change is the law of nature’ (parivartan prakriti ka niyam hai), and this is also sermonised in the Bhagvad Gita. It might guide us not to be averse to change, as it is bound to happen. But through ‘purusharth’ desired change can be brought in the larger public interest. Purusharth is also required to fight evils and injustice.

Going further we find that Gandhiji made use of these positive elements of ‘dharm’ to create the idealist symbol of ‘Ramrajya’, and in the process used politics as a constituent of dharm, which is not a synonym of religion. The emphasis on a separation between religion and politics in western democracies and socialist states does not apply in the Indian context.

When JP calls for a cultural change as part of total revolution, he is challenging those symbols and practices which are used and promoted for the vested interests of the dominant classes of society, while the essence of real ‘dharm’ remains out of the reach of the weaker ones. As he remarked, ‘The ancient concept of Dharma has to be revived, and the appropriate Dharma for a democracy has to be evolved.’

So the call for total revolution should be seen as a call to overhaul the system, the enterprise of cleaning, purifying (shodhan), or rejuvenating (punarnavaa).

Sheodayal is a Hindi writer, editor, novelist, poet and essayist.