Rethink the Slight of Kala Pani

The lazy and often ill-informed perpetuation of this term justifiably rankles Islanders

Unhealed sentiments fester in the Indian psyche. The diversity and plurality of our society, its sheer scale, seem also to have cursed us with discrimination inherited and biases hard to uproot. Routinely, one section of this wary society will be pitted against another. The fortuitous statesmanship of national leaders around Independence was alive and sensitive to these faultlines, which they made deliberate efforts to overcome; the Ambedkar-led Constitution of India remains a shining example of such philosophy.

The national integration it envisaged must not only heal social wounds, but also remake the sheer ‘distance’ afforded by the expanse and reality of independent India. The challenge of overcoming ‘distance’ is exemplified by the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which earlier suffered notoriety as Kala Pani – a term suggesting the putrefaction of an individual’s character and social existence, the irreversible ‘Black Water’ across the seas.

1,200 kilometres distant from the shoreline of ‘mainland’ India, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands played an invaluable and sadly lesser known role in India’s freedom struggle. It was here that Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose first hoisted the Indian national flag in Port Blair in 1943, when it was under Japanese occupation, and declared the Islands the first territory freed from the British.

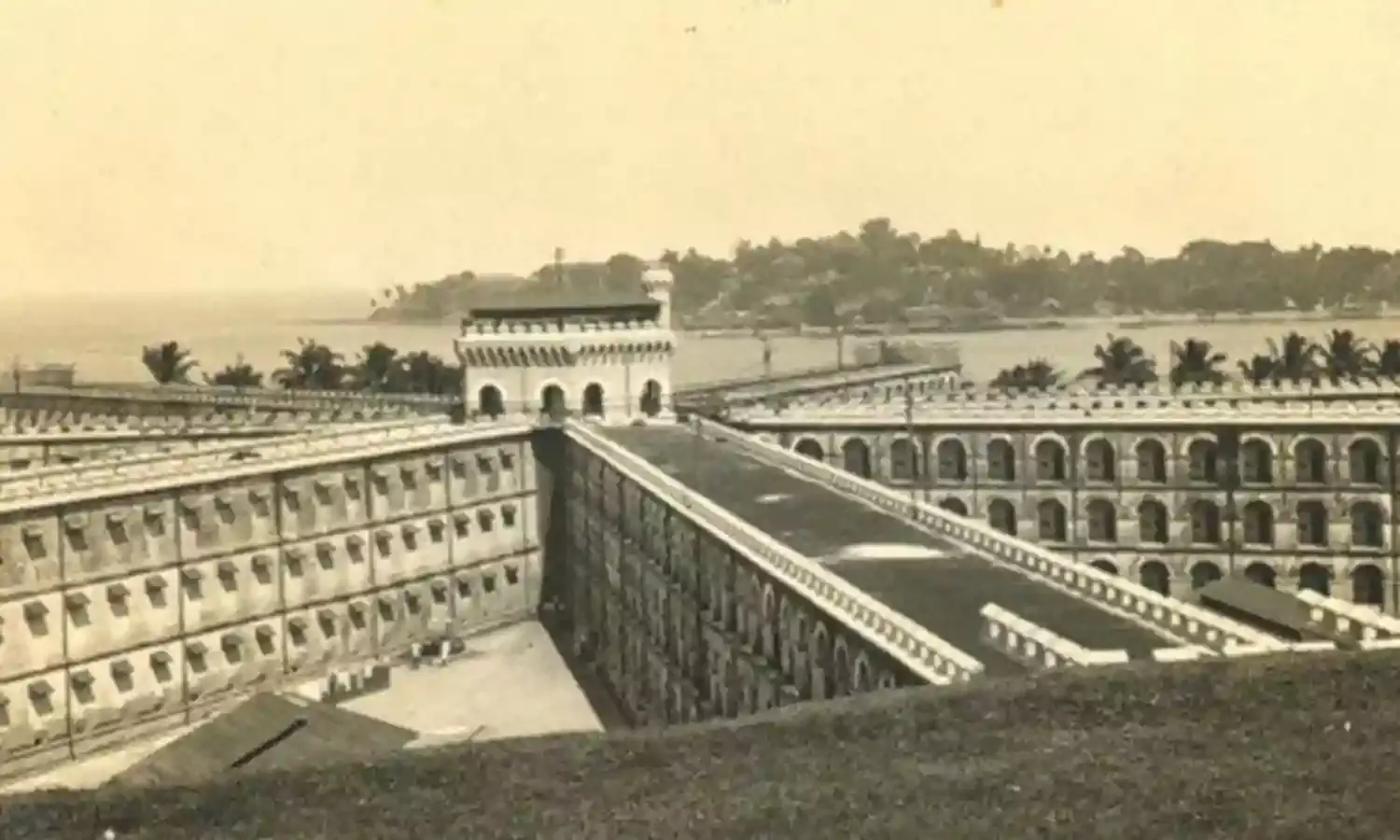

The infamy of the Cellular Jail made the islands synonymous with penal punishment. Many a revolutionary was exiled to his fate in this dreaded place. Potential incarceration to Andamans also meant the loss of caste and social exclusion to these men of faith, besides the doom of ‘never returning home’.

Seventy years on this land of freedom fighters typifies the idyll of ‘mini India’, which is still an aspirational work-in-progress on the mainland. The peaceful coexistence of latter day immigrants and the indigenous tribes: the Jarawas, Onges, Great Andamanese, Sentinelese, Shompen, Nicobarese, is unparalleled anywhere in the world. A quaint Hindustani dialect binds together the immigrants, who know virtually no cultural or religious animosity, and revel instead in multiple identities subsuming Bengalis, Tamilians, Malayalees, Sikhs, Biharis in a utopian setting, now befittingly called the Emerald Islands.

But there is a divide, which paradoxically also unites the diversities within these Islands. It is the divide of historical perceptions, illusions and the distance the Islanders perceive vis-à-vis the Mainlanders.

Today, the lazy and often ill-informed perpetuation of the term Kala Pani justifiably rankles the Islanders, who are the proud progeny of forgotten freedom fighters. It betrays a perception among Mainlanders that they have only a transactional and unconcerned relationship with the Islands, with their tenure-bound status as tourists or government employees.

Like many continuing stereotypes that afflict insensitive conversation, the term Kala Pani retains a limiting and regressive connotation. It implies punishment. A term that ought to be nuanced as sacred given the historical sacrifice, is solely understood in this disparaging context, perpetuating the divide with the Mainlanders.

Such exclusivist language increasingly dominates the modern Indian narrative, and threatening the fragility of a relationship born of the historical, social and physical distance of the Andamans from the mainland.

These islands are an uber-strategic Indian outpost, now at the forefront of the fructifying potential of the Look East policy, and also defending India from challenges emanating from the Rising East.

With this backdrop, implied allusions to Andaman and Nicobar as the veritable boondocks, ‘Timbuktu’ or the ‘forbidden frontier’ by senior functionaries of the government, are both discriminatory and insensitive.

The recent drama involving internal fissures within the top intelligence agency contained this allusion, as one of the key officials investigating a crucial and perhaps uncomfortable enquiry, was suddenly posted out to Port Blair. The opposition parties latched on, terming it a ‘saja e Kala Pani’ (Black Water sentence).

Due to certain logistical, infrastructural and educational constraints, the Andamans may be avoided by some government officials, much like the ‘forward areas’ in the military outposts. Yet such a posting should never be seen as a punishment posting, in today’s day and age.

It is a rare privilege to serve the nation’s Shining Outpost. As in the military, only the finest, toughest and most deserving are entrusted with the task of defending the extreme frontiers. Lazy barbs about posting out an official to ‘cool off’ or to ‘sort out’, as is the wont in official circles, cannot be extended to the entire gamut of officials who loyally seek to serve these distant lands of ours.

Like many terms in common parlance which are corrected, withheld or at least contexualised, to undo their hurt to a community of people – the term Kala Pani requires a deep rethink of usage. It affixes and perpetuates the dark context. This must be taken away and only its historical relevance, celebrated and revered.

Lt General Bhopinder Singh was formerly lieutenant-governor of Andaman & Nicobar and Puducherry.