Deja Vu for Dalit Women: The MeToo Movement in India

Many upper caste hindu women are perplexed, and share deep anxieties, about appropriation

Talk to any Dalit woman, she will tell you how her voice has long been ignored. Look at the history of the Dalit, Leftist or Feminist movements in India - you’ll know that women from Dalit, Adivasi or Muslim backgrounds have always been active participants, at the forefront of political assertion and mobilisation.

It is disheartening to hear people say that the Dalit Feminist Movement is ‘next’ or has yet to ‘arrive’. As if it never existed, never questioned the status quo - or as if it must learn from the mainstream feminist movement?

This silencing of narratives, assertions and the political understanding innate to Dalit women has created a weak, sullen, an incomplete #metoo movement in India.

Indeed it’s a crucial point in time, as hundreds of women from diverse backgrounds (of caste, class and sexuality) have come forward with their personal narratives of sexual harassment and abuse. We should be proud of ourselves that we in large numbers, from different corners of India, have embraced our fears, insecurities and vulnerabilities.

After a long time, we are in our element: calling a spade a spade, asking for accountability and acceptance from patriarchal, misogynist and heteronormative apparatuses.

In 2017, when Raya Sarkar a Dalit law student, for the first time compiled testimonies from victims of sexual harassment and created a list of sexual offenders in academia, the feminist movement recognised her contribution. However, it forgot in due time that a Dalit woman started this mass movement.

Way back in 1992, it was Bhori or Bhanwari Devi’s resilience and mental strength that led to the formulation of the Vishakha Guidelines mandated by the Supreme Court.

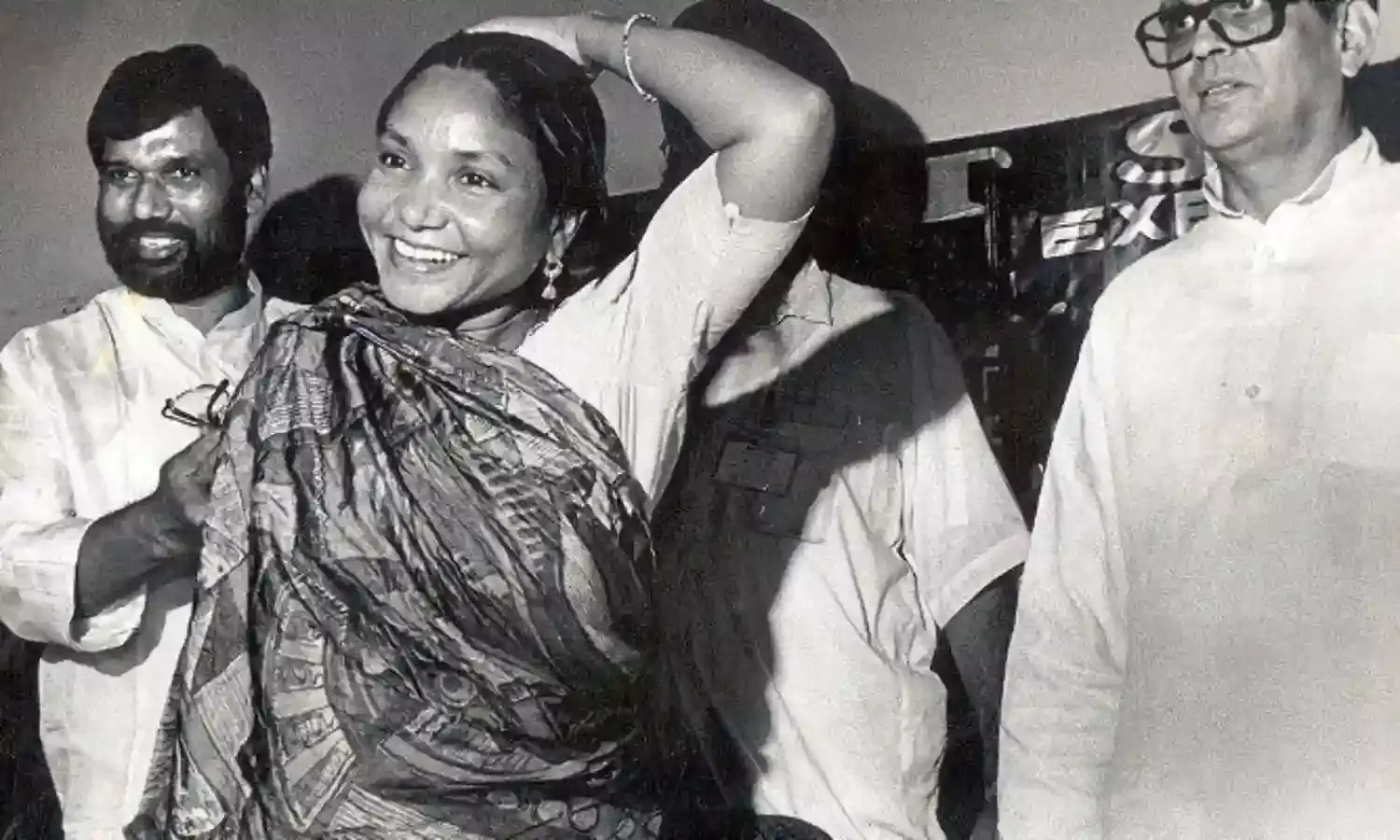

Phoolan Devi the fierce, bold and charismatic bandit popularly known as ‘Bandit Queen’ served as a Member of Parliament in her later years. She was one of a kind, the only woman in the gang, and made history by taking on upper caste men. In one account, her gang shot dead 22 Rajput men after lining them up in a row. The infamous Behmai massacre stirred controversy and led to the resignation of VP Singh, then the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh.

Phoolan Devi was unstoppable, bold and couldn’t be captured until she surrendered herself to police officials in 1983. Then in 1994 Mulayam Singh of the Samajwadi Party withdrew 84 charges against her and she contested elections. She was twice elected to the Lok Sabha as the MP from Mirzapur.

Such is the strength of Dalit women: unmatched, unbound commitment to society, and a zeal to fight for rights that gives strength and flesh to the mainstream feminist movement.

We consider historical accounts. The 19th century saw Nangeli, a Dalit woman who challenged mulakkaram, the exploitative breast tax imposed by Brahmins on low caste women. Low caste women were expected to pay tax in proportion to the size of their breasts. On a few occasions Nangeli refused to uncover her breast and pay the tax, while officials continued to visit her home demanding it. In protest Nangeli in frustration and distress chopped off her breasts, which later on led to the abolition of the breast tax.

Such oral histories and accounts of Dalit women continue to be ignored by professional historians as well as the mainstream feminist movement.

Born in 1926, Gulab Bai or Gulab Jaan was the first female artist of the traditional nautanki theatre genre, and cofounded the Great Gulab Theatre Company. In 1990 she was awarded the Padma Shri, the state’s highest civilian award. Gulab Bai belonged to the Bedia community, a low caste community engaged for generations in the performance arts. Nautanki along with Parsi theatre led to the foundation of drama and films in later years.

Savitribai Phule, Shantabai Dane, Mukta Sarvagod, Tarabai Shinde, Kumud Pawde, Urmila Pawar, Rajni Tilak, Ruth Manorama, Anita Bharti, Sampat Pal - the web has a compilation of various Dalit women’s lives and contributions if one wishes to educate oneself…

Women from minority backgrounds are well aware and accustomed to the everydayness of sexual violence and abuse. Day after day, consistently they undergo covert and overt forms of apathy, structural violence and misogyny.

Due to their low position in caste/religious or gender terms, often they do not wait to share their narratives of violence; they do not wait for due process. Often they call out sexual predators, beat them up, fight with patriarchy head on; day after day, for their entire lives.

They are aware that bureaucracy or state apparatuses won’t be with them in time. They fight their own battles. They don’t wait to be rescued. They challenge. They assert. They struggle with the consequences.

Media reporting of caste based violence, gang rapes and murders are examples of Dalit women assertions, their spirit of standing up for themselves.

But Brahmanical patriarchy works in surprising ways, in entanglements with troubling middle-class morality. It is upper caste Hindus’ sensibilities that make ‘issues’ an issue. From time immemorial Dalit women have been fighting and raising concerns around sexual violence, gendered pay, labour conditions in the informal sector, patriarchy, property inheritance, political leadership, education and health.

Because they bear with the worst. Being at society’s bottom rung, they deal first hand with issues of poverty and discrimination.

Thus the #MeToo movement for women from minority and marginalised backgrounds, especially dalit women, is a moment of deja vu. It calls for a critique of the mainstream feminist movement in India once again, as decades ago, for sidelining the histories and stories of Dalit women. This led on multiple accounts to the muting of Dalit women’s voices - to the denial of appreciation and timely acknowledgment of their concerns.

But now it's different. There are stronger, spiralled and well articulated voices of Dalit women. Many of whom are first or second generation learners in their families, and have access to technology and digital resources. They are using social media platforms to their advantage, for building networks and arguments…

How would or should the #MeToo movement in India address questions around intersectionality? What form and shape would it then take? What concerns would it point out to its allies? How would it deal with the risks of appropriation?

Let us deliberate on some of these questions, to bring intersectional perspectives into the mainstream feminist movement.

There’s a danger in assuming that one may be resorting to a comparison of some sort, ‘privileging’ one identity over the other, or drawing easy parallels between the intensity, lives and struggles of women.

No, to really integrate intersectional perspectives into the #MeToo movement is not to trivialise the experiences of upper caste women or advantaged women, nor to say their struggle is invalid.

Intersectional perspectives stress on embedding a critical thought process to understand that women, although under all sisterhood likeliness, are not homogenous. They represent various identities, views, values, understandings and embodiments of patriarchy, sexism and misogyny.

We must therefore take into account the holistic being of women, rather than consider them as one.

To reiterate, it is extremely important to take into account the everyday struggles and #metoo movements of Dalit, Adivasi and Muslim women, along with personal narratives. I believe this will point towards nuanced politics, thought processes and engagements, rather than being just a privileged articulation of one’s own violation.

There should be regular eruptions of solidarity and acceptance, that women from marginalised backgrounds have been at the center of the feminist movement, and continue to solidify and lead it.

Many upper caste Hindu women are perplexed, and share deep anxieties, about whether to articulate for ‘dalit women’, or for women from other vulnerable backgrounds, as there is always a risk of appropriation. It is the long standing battle of Dalit women that has aroused this anxiety and I see it as a victorious moment in itself.

However, I personally stand for and by the individual, from any caste and class consciousness, to talk about intersectional issues in the feminist movement, as long as they are in sync with their own privileges, caste location and entitlements.

For me, the annihilation of caste isn’t and mustn’t be the burden of minorities alone. Caste has to be eradicated, if at all, through committed solidarities, camaraderie and an alliance of people - women, men, LGBTQIs from various caste, religion and class locations.

For the #MeToo movement to be holistic, impactful and consistent, it must have intersectionality at its core. How would this feature in cases of personal experience?

I believe intersectionality gives courage and voice to stand up for oneself, in naming the accused; it gives lessons to the mainstream feminist movement to stand tall, and draw spirit and resilience from Dalit women’s experiences.

Intersectional perspectives teach men to be accountable for their actions, and have insights for women on how to be righteous. This means, always and always giving the benefit of doubt to a woman first, even if one doesn’t know her personally.

Intersectional perspectives provide the nerve to engage with men - known or unknown - letting them know that as a woman your solidarity first, will always be with another woman.

Intersectionality, in my opinion is matured politics, because it understands that social stature, fame, or the financial, political or cultural nature of a man has no bearing on his ability to sexually violate another person. It humanises sexual offenders by recognising that they could be one of us, our fathers, uncles, brothers or lovers.

As women, we must always support other women, report cases of sexual violence or other violations, take desperate measures to protect vulnerable groups. We must however always be ready, to give the benefit of doubt to women and fight with similar resilience, even in a situation where one of our own is being accused.

We will never ‘arrive’ at the Dalit feminist movement because it has always existed in its true spirit, guiding the mainstream feminist movement for decades. But the mainstream feminist movement is certainly lagging behind when it comes to learning the deeper moral, ethical and life lessons - intersectional perspectives from women of marginalised sections, especially Dalit women.

If it would do so, then perhaps the #MeToo movement wouldn’t be criticised for being the self-righteous and privileged account of upper-caste Hindu women in India.

(Jyotsna Siddharth is an actor, anti-caste activist and writer based in Delhi. She is a founder of Project Anti-Caste, Love and Co-founder of Sive. She has conducted workshops with colleges in Delhi University on Questions of Social Identities in Romantic Relationships. She has a Masters in Development and Social Anthropology and a recipient of Chevening Scholarship (2014).)