The Constituent Assembly Feared that a Party Man Might Become CEC

Ask your candidates if they will help Mussalmans, Gandhi advised

The flagrant violation of the Model Code of Conduct, particularly by top leaders of the ruling party at the Centre and by the Prime Minister during the present general election being organised across the country, sharply brings to light the calculated ineptitude of the Election Commission.

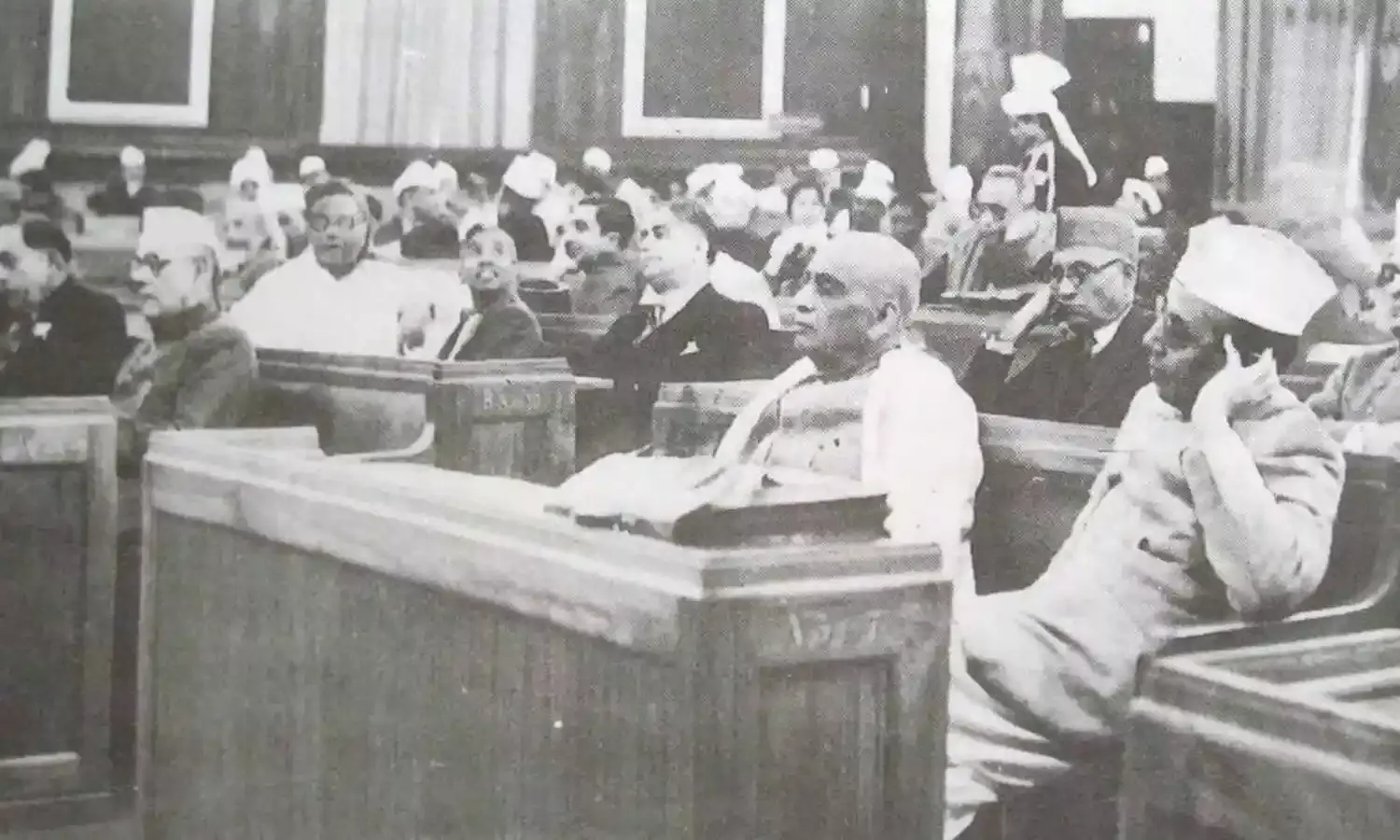

A peek into the debates of the Constituent Assembly, when the article concerning the Election Commission was under discussion, reveals the cautionary words of many distinguished Members who anticipated that a situation might come when leaders wielding power would vitiate the purity of the electoral process and compromise the integrity of the mechanism for conducting elections.

What is now Article 324 of the Constitution dealing with the Election Commission was Article 289 in the draft constitution. It was moved by Dr B.R.Ambedkar on June 15, 1949. He informed the Constituent Assembly that initially it was the opinion of the Committee on Fundamental Rights of the Assembly that

“the independence of the elections and the avoidance of any interference by the executive in the elections to the Legislatures, should be regarded as a fundamental right and provided for in the chapter dealing with Fundamental Rights”.

However, Dr Ambedkar went on, when the matter came up while discussing the fundamental rights the Assembly expressed the view that while there was no objection to regarding election-related matters as part of fundamental rights, these should be specified in some other part of the Constitution, and not in the chapter on fundamental rights.

According to Ambedkar the Assembly expressed, “without any kind of dissent, that in the interest of the purity and freedom of elections to the legislative bodies, it was of utmost importance that they should be freed from any kind of interference from the executive of the day.”

The fundamental issue manifested in the legislative intent of the Constituent Assembly was for an Election Commission which should be free from any influence whatsoever, from any authority, including the executive of the day and should act as an impartial body for the “superintendence, direction and control of the preparation of electoral rolls for, and the conduct of, all elections”.

Some of the illustrious framers of our Constitution, while complimenting Ambedkar for moving the article for the establishment of an impartial poll body, expressed the apprehension that a political formation might abuse the provisions in the Constitution to manipulate the Election Commission for its advantage in the hustings.

Professor Shibban Lal Saksena while participating in the discussion on June 15, 1949 cautioned the Assembly by saying that “it is quite possible that some party in power who wants to win next elections may appoint a staunch party man as Chief Commissioner”.

Such remarks made by Professor Saksena seventy years back on the floor of the Constituent Assembly sound so contemporary, at a time when several decisions taken by the Election Commission are not above board, and it has acted only half-heartedly against recurring and wilful violations of the Model Code, mostly by the top leadership of the Union Government during the election process.

The inordinate delay on the part of Election Commission even in taking cognisance of some violations, and its mild action taken in some selective cases, completely ignoring the infractions committed by the Prime Minister when he panders to communal passions, or appeals for votes by referring to the defence forces and the Balakot airstrike in complete disregard of the guidelines issued by the Election Commission, testifies to the EC's compromised position, and the denting of the purity and integrity of the electoral process.

Professor Saksena also warned by saying that in future there would not be a Prime Minister like Jawaharlal Nehru known for independence and impartiality, and said with apprehension that someone else with weak credentials might occupy the office of Prime Minister and abuse his right by appointing an unsuited person as Chief Election Commissioner, who in turn would work havoc on the electoral process.

Therefore, he wanted that the Government's decision to appoint a Chief Election Commissioner should be subject to the approval of the Parliament by a prescribed majority.

It is fascinating to learn from the Constituent Assembly Debates that Shri H.V.Pataskar, who went on to become Union Information and Broadcasting Minister, while participating in the debate asked Dr Ambedkar to deal firmly with people who "trifle with democracy on linguistic, racial, or other considerations".

A distinguished Member Shri Hriday Nath Kunjru expressed the view that "If we cannot expect common honesty from persons occupying the highest positions in the discharge of their duties, the foundation for responsible government is wanting, and the outlook for the future is indeed gloomy."

The absence of common honesty in the conduct of so many public figures and government agencies including that of the Election Commission makes our future gloomy and bleak. Therefore, Kunjru suggested that Ambedkar's proposed Election Commission should be modified to "consist of impartial persons, so Election Commissioners may be able to discharge their duties fearlessly". He demanded safeguards to keep the election machinery free from political influences both from the States and Centre, and observed with prescience that:

"We are going in for democracy based on adult franchise. It is necessary therefore that every possible step should be taken to ensure the fair working of the electoral machinery. If the electoral machinery is defective or is not efficient or is worked by people whose integrity cannot be depended upon, democracy will be poisoned at the source; nay, people, instead of learning from elections how they should exercise their vote, how by a judicious use of their vote they can bring about changes in the Constitution and reforms in the administration, will learn only how parties based on intrigues can be formed and what unfair methods they can adopt to secure what they want".

These words spoken seventy years ago assume critical relevance when question marks are raised on the impartial functioning of the Election Commission and intrigues resorted to by the political formations to adopt unfair means for vitiating the electoral process, and "managing" it.

Dr Ambedkar admitted on June 16 in his reply that "there is no provision in the Constitution to prevent the appointing of either a fool or a knave or a person who is likely to be under the thumb of the executive." It makes us mindful of the omissions of the present day Election Commission which gives the impression of being an arm of the executive.

Its studied silence on the functioning of NaMo TV telecasting the Prime Minister's speeches and all other pronouncements without taking permission from any legitimate government body, and its inaction on the communally provocative remarks of the Prime Minister during the election campaign, clearly proves the apprehensions of the framers of the Constitution.

In 1920 Mahatma Gandhi wanted voters to ask the candidates contesting elections certain questions, and urged them to cast their votes based on answers to those questions. Those questions reflect the spirit and temper of the second decade, but also are of deeper and abiding significance for our own time, marked by the emergence of majoritarianism and polarising tendencies in politics and in public life.

One question was, "Do you hold that there is not the remotest likelihood of India’s regeneration without Hindu-Muslim unity? And if you think so, are you, if a Hindu, willing to help the Mussulmans in all legitimate ways in their trouble?"

In other words Gandhi wanted voters to vote for candidates who would stand by Muslims in their hour of need, and espouse the cause of Hindu-Muslim unity for regeneration of India. Such interrogation on the part of voters is the need of the hour now when India is in the thick of the election campaigns. Gandhi wanted an electorate which would remain free from all influences. It is worthwhile to quote his exact words. He wrote:

"My attempt is to point out that we need an electorate which is impartial, independent and intelligent. If the electors do not interest themselves in national affairs and remain unconcerned with what goes on in their midst, and if they elect men with whom they have private relations or whose aid they need for themselves, this state of things can do no good to the country; on the contrary, it will be harmful".

Wise words articulated a hundred years back assume deeper significance for the 2019 general election and beyond. If India requires an "electorate which is impartial, independent and intelligent" the country requires also an Election Commission which is a role model of impartiality and independence.

Let the vision of Gandhi and the legislative intent of the Constituent Assembly in this regard be our guiding spirit towards safeguarding the purity and integrity of the electoral process.