When Amarinder Singh Saved Us From the Punjab Police

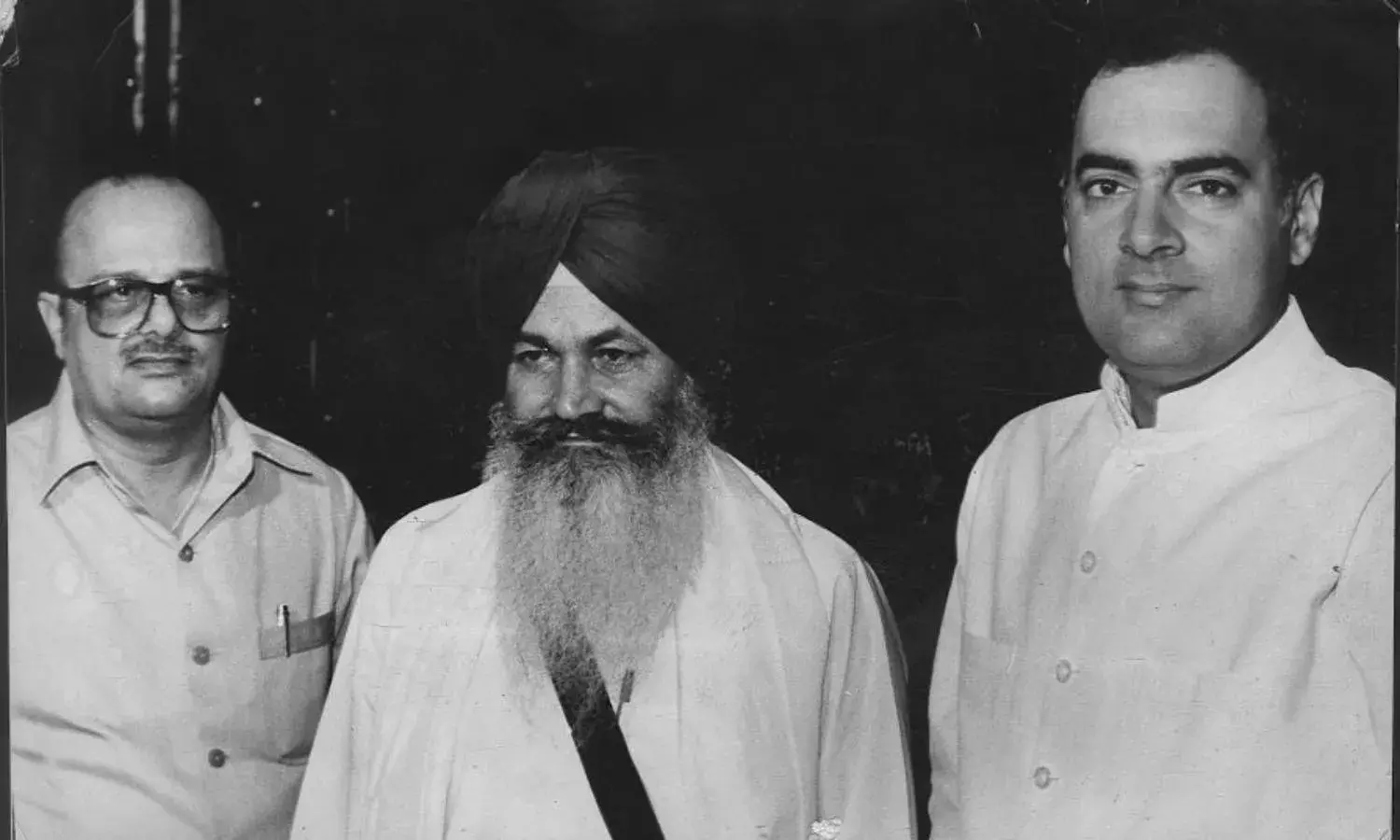

Kandu Khera census 1986

Often journalists find themselves on the wrong end, for doing little more than their jobs. Our skirmishes with the police could fill a book, particularly those of us who grew up in journalism during the 1980’s described by our seniors then as the decade of violence in India. Journalism too was proud and irreverent then, and hence as practitioners we had the arrogance of the profession and of youth, to challenge the mightiest in government. Police officers often bore the brunt of our wrath, as they were the face of authority.

As young reporters we would charge into situations, with just one mission. To get the story, particularly if it exposed the government of the day. Ours was pure driving passion, and so it was that one set off early one morning in 1986 to cover the census of a Punjab-Haryana border village Kandu Khera. Sounds ordinary, but it was anything but that. It was in the wake of the struggle for Khalistan, Operation Bluestar, the assassination of Indira Gandhi and then the Rajiv Gandhi-Longowal Punjab Accord for peace in 1985. Since 1982 Puniab had been in turmoil, and having covered every bit of it from the first morcha and the hijacking of the Indian Airlines flight in 1982 onwards, it was but natural that we would rush to Kandu Khera for the ‘historic’ census.

Historic as this little area was going to determine the future for Chandigarh, as it was to choose between Haryana and Punjab by declaring itself Hindi speaking or Punjabi speaking. The Union Home Ministry officials were there in strength, but the then Akali Dal government in Punjab was in obvious charge with its police deployed all across to supposedly supervise the census. Surjit Singh Barnala was the Punjab Chief Minister. Harchand Singh Longowal had been assassinated a few months ago, in August 1985, for signing the accord with Rajiv Gandhi a month earlier. And clearly the situation was very very tense, to put it mildly.

We hired a car from Delhi and along with photographer Sondeep Shankar ---we were both with The Telegraph in those days-- reached Kandu Khera amidst all the bandobust. We went into the main village to speak to the people,and realised pretty soon that while the people were speaking Punjabi, a Haryana pradhan was trying to influence them to declare their language as Hindi. The police was not inside the village, and we realised that there could be violence as the atmosphere inside was getting very tense. So we---by this time journalist Sankarshan Thakur had joined us---like good citizens decided to warn the cops outside, to be careful, that there could be trouble.

We came out, spoke to the DGP in charge, he was visibly hostile. Anyways having done our duty we turned to go back into the village but he blocked our way and said we did not have his permission to go back. We protested, reminded him of our rights as journalists, and told him that he had no right whatsoever to stop us. That we had come out of our own will to inform him but our work inside was not finished and hence we were going back in. I turned along with the others to walk back, when I saw him gesture to the armed men and next thing we knew we had been surrounded by the police, with guns pointing at us.

Sondeep Shankar’s camera was snatched and he was pushed at gunpoint towards a van. One burly police officer caught hold of Sankarshan Thakur with his muffler, choking him. Sankarshan turning almost blue in the face, with his feet dangling in the air, managed to say, “he is choking me”. I was just behind with two cops with rifles pointing at me, but hearing this I started pummelling the cop who was dragging Sankarshan from behind. Stunned, he let go and turned to me, and I was hit on the back by the rifle and pushed along towards the van. I saw our cab driver at a distance in the stunned crowd watching this attack, and I gestured to him to follow us. The cops saw that and after a while he along with the other cab driver who had brought Ritu Sarin also (as we learnt later) were both brought by the police to the van. We were pushed inside like criminals with armed police guards.

We kept telling them to wait as we knew Barnala was arriving, along with Amarinder Singh who had joined the Akali Dal and was a Minister in the state government. We soon realised that the cops were keen for us to be taken away before the CM and others arrived. They kept telling each other, “go go, take them away”, even as other officers stopped them saying there is “one more, where is that journalist, get her too.” The reference was to Ritu Sarin who had arrived after us, and gone into another village in the vicinity. The cops did not know where she was, and finally when they could not find her, they whisked us off before the politicians arrived.

On the way they abused and threatened us. Said that we would be beaten, our bones broken, and thrown across the border into Pakistan. It was a long drive, and if the intention was to terrorise us, they had somewhat succeeded. They took us to what seemed to be an abandoned rest house in the middle of nowhere, dropped us there with armed guards, and the van left. This was in the morning, and we were in the sun for a while and then locked inside a room. Sondeep, Sankarshan and I.

Back at the site Ritu Sarin emerged from the village, and started asking about us. The Home Ministry chaps, witness to it all, did not say a word. She was told by the Punjab police and officials that we had gone back to Delhi. Not believing this she went to the car park. And a driver there informed her that we had been taken away. She went back and tried to raise a storm but no one listened, and by that time Barnala and Amarinder Singh had arrived with their entourage. She told them the story and expressed her fears about our safety. The CM questioned the police and was told that they had no idea, and that we had gone back to Delhi. Ritu pointed out the two locked cars and said that the drivers too had been taken away. But the police insisted to their political masters, that the journalists had gone away, and they had no idea how.

It took a determined Ritu Sarin to convince Amarinder Singh that something was amiss. Finally he managed to get the truth out of some of the eye witnesses. It was clear from this that the police had planned to do what they had threatened, beat, kill, who knows as those were the days of violence at all levels in Punjab. Unrest, anger, political turmoil. Amarinder Singh then ordered the cops to take him to where we were--- I don’t really know what happened---but he drove the long distance with Ritu and others in tow.

It was late into the night and we had given up hope by then. As it was clear that they were going to keep us alive until the census was over, and then…. We feared the worst. We heard the cars drive in and the door opened with Singh and Ritu Sarin standing there. We could not believe our eyes. The relief was enormous. He had realised the enormity of the situation and knew that if he did not come personally to rescue us, we might not be rescued at all. He certainly could not trust anyone to follow his instructions, as the police had lied through the evening about us. And he was concerned enough to drive the long journey, find us, and take us to safety.

We were taken back to the census site. Barnala was waiting there too. The cops would pass us by, and whisper threats. ‘You leave here and just see what will happen to you” was the whispered refrain. We were to go back in our own cars but hearing this the Chief Minister gave his own escort, and his cars to go back to Delhi. En route we were stopped by cops---this time the Haryana police---who insisted we accompany their escort to a government rest house as the Haryana CM Bhajan Lal wanted to meet us. We had no choice.

The story of our abduction had spread like wildfire. And Bhajan Lal was waiting to greet us, sympathise, and thereby hopefully to get us to write that the villagers of Kandu Khera were Hindi speaking and hence the census should favour Haryana. We refused his cup of tea, told him we were journalists, and despite the incident would write what we had seen, according to the facts that we had gathered.

For us Kandu Khera was clearly Punjabi speaking. We met the then Minister of Interiors Arun Nehru to lodge a formal complaint against the Punjab police and his own Ministry officials. Sitting behind the paperless desk that he had introduced in the Rajiv Gandhi government, he heard us out. There was no sign he was convinced. We left muttering, “what else could we expect from him.” But a couple of years later I ran into Barnala and he recognised me with, “do you know how much trouble you created for me, Arun Nehru was on my back all through, did not give me a moments rest until I had taken action against the police officers.” We did not know, and being totally out of the pockets of politicians, we were never told.

We are starting a behind the news column for journalists to share experiences that they have not necessarily written about. All are invited to contribute. We are making a start with three articles over the next few days from The Citizen founder Seema Mustafa. The first is https://www.thecitizen.in/index.php/en/NewsDetail/index/9/17025/In-Ballia-In-1981-To-Cover-the-Rape-of-a-Young-Dalit-Girl