The New Budget

Paradoxes

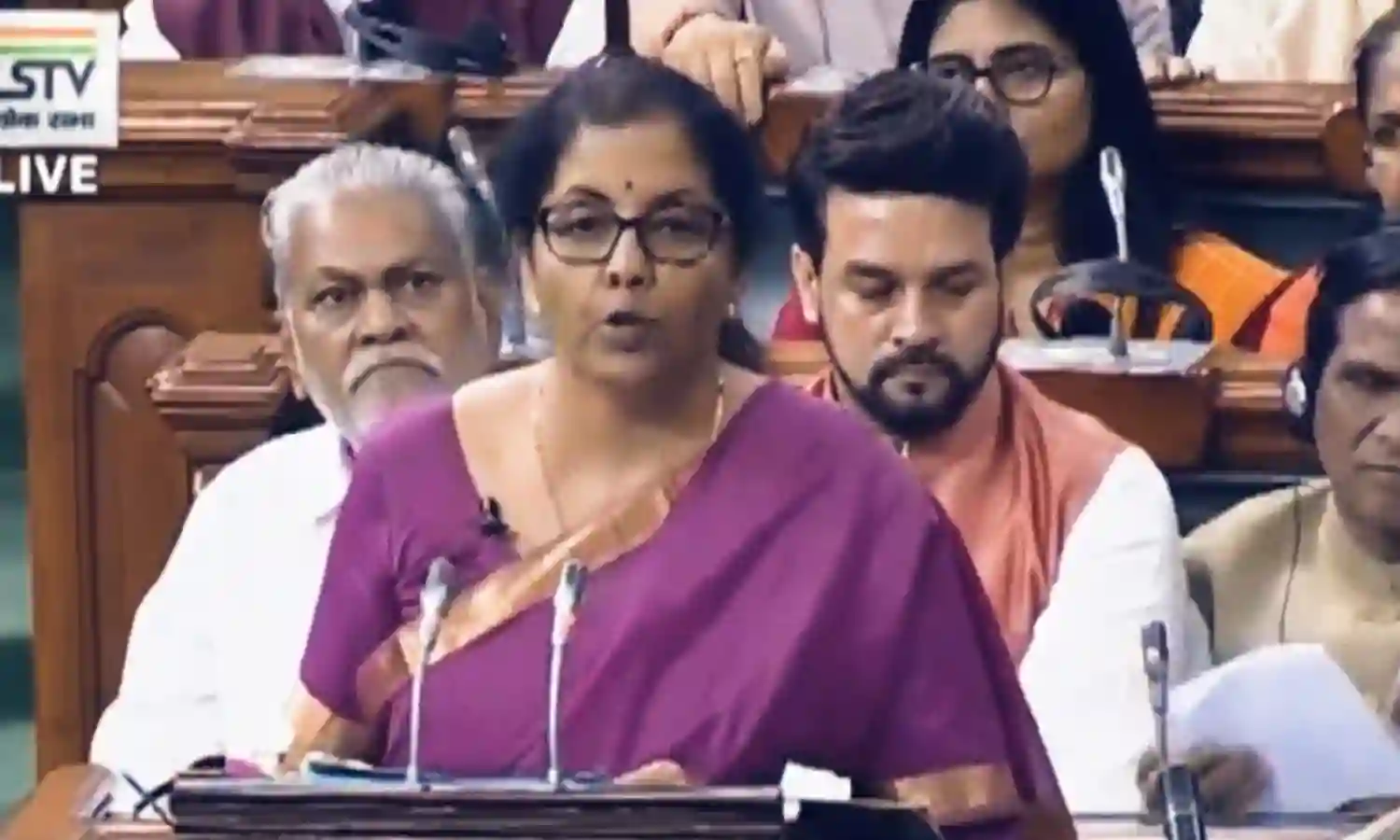

Nirmala Sitharaman’s Budget is full of paradoxes. On the one hand, the Finance Minister’s narrative in her 2019-20 Budget speech was that of “gaon, garib, aur kisan,” or villages, poor, and farmers were central to her concerns. But the numbers budgeted for rural development for 2019-20 tell another story where the allocations for the farm sector are marginal while real policies favour further privatisation and likely marginalisation of small farmers and labour.

Deeper analysis has already shown that the increases in allocation for the farm sector is by just 4 percent to ₹1.41 trillion. This is far less than the 13 per cent increase in the Budget’s total expenditure this year. Further, the largest expenditure head under rural development is the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme (MGNREGP) which in 2019-20 is only ₹60,000 crore. A decline from ₹61,084 crore last year. Which reveals a trend of decreasing interest in farm labour.

Even as the PM spoke of focus on water, the newly created ministry of Jal Shakti, which includes the departments of water resources, river development, Ganga rejuvenation, drinking water and sanitation, has a budget allocation for the for the current year at ₹28,262 crore, which represents only a 2 per cent increase over what was spent under these departments in 2018-19. Economists, environmentalists and others are therefore asking if Jal Shakti is so critical then why allocate such meagre resources?

The proposal for agriculture and allied activities, appears to be enlarged. But as several analysts who have deconstructed the Budget show, due to other outlays the ₹64,916 crore increase in one year, of ₹55,000 crores is dedicated to the PM-Kisan scheme and ₹900 crore is on account of farmers’ pension. Several analysis of Budget numbers show that the increase on other agricultural schemes and projects including on much needed research and development is only about ₹9,000 crore. A comparison made by economists with last year shows that the government spent about ₹20,000 crore on PM-Kisan scheme and this would go up to ₹75,000 crore in the current year. But the government’s decision to expand the coverage for PM-Kisan to include all farmers, the financial requirement would be higher at ₹87,000 crore. It has thus been rightly questioned by analysts that just ₹9000 crore for the farmers’ scheme will be highly insufficient.

Clearly the budget while seeking to construct the Modi governments’ pro-Bharat image in reality makes some symbolic moves to increase taxes on the rich, but which in reality are insignificant. This move appears to appease the Swadeshi lobby’s demand for raising the tariff walls to protect domestic industry and shifting resources to the poor. But the policy package behind the budget takes more steps to open up the Indian economy to foreign capital. It creates paths for more reforms including privatisation and greater private sector role in infrastructure like the railways and selling of public assets.

Presenting the Budget as pro-Bharat is a political mirage. The numbers as well as the policy behind these show that this Government will be partial to the greater entry of foreign capital in new areas, privatisation of public assets, and changing labour laws that will push against unions and social justice claims with a new labour code, which is supposedly simplified. The cover of the Budget as being pro-Bharat is contrary to real economic nationalism with the welfare of the farmers and labour in mind.