Gandhi’s Contribution to Communal Harmony

The atmosphere in which we grow will determine which thinking will flower

It is well known that Mahatma Gandhi began his meetings with a multifaith prayer, reciting portions from various religious texts. Gandhi was a firm believer in the idea of communal harmony. From childhood as he cared for his father, he got an opportunity to listen to his father’s friends belonging to different religions, including Zoroastrianism and Islam, talk about their faith.

Interestingly, at this stage he was biased against Christianity as he heard some preachers criticise the Hindu gods, and because he believed that drinking alcohol and eating beef were an integral part of this religion. It was only much later, in England, when a Christian who was a teetotaller and a vegetarian encouraged him to read the Bible, that Gandhi gave a serious thought to Christianity.

Once he started reading Bible, especially the New Testament, he was enthralled and particularly liked the idea that if somebody slaps you on the right cheek, offer the left.

Even before reading the Bible, Gandhi had got this idea from perusing various religious books that evil should not be countered with evil but by good. He was exposed to different religions but doubted whether he was a believer in his childhood. Nevertheless he was of the firm view that all religions deserve equal respect. Hence the seeds of communal harmony were sown even at a young age for him.

In fact, Gandhi said he became more atheistic after reading the Manusmriti, as it supported meat-eating. The essential learning he imbibed from these religious works was that this world survives on principles, and principles are subsumed in truth. Thus from his childhood truth was a highly held value which became the basis for living his life and the various actions that ensued.

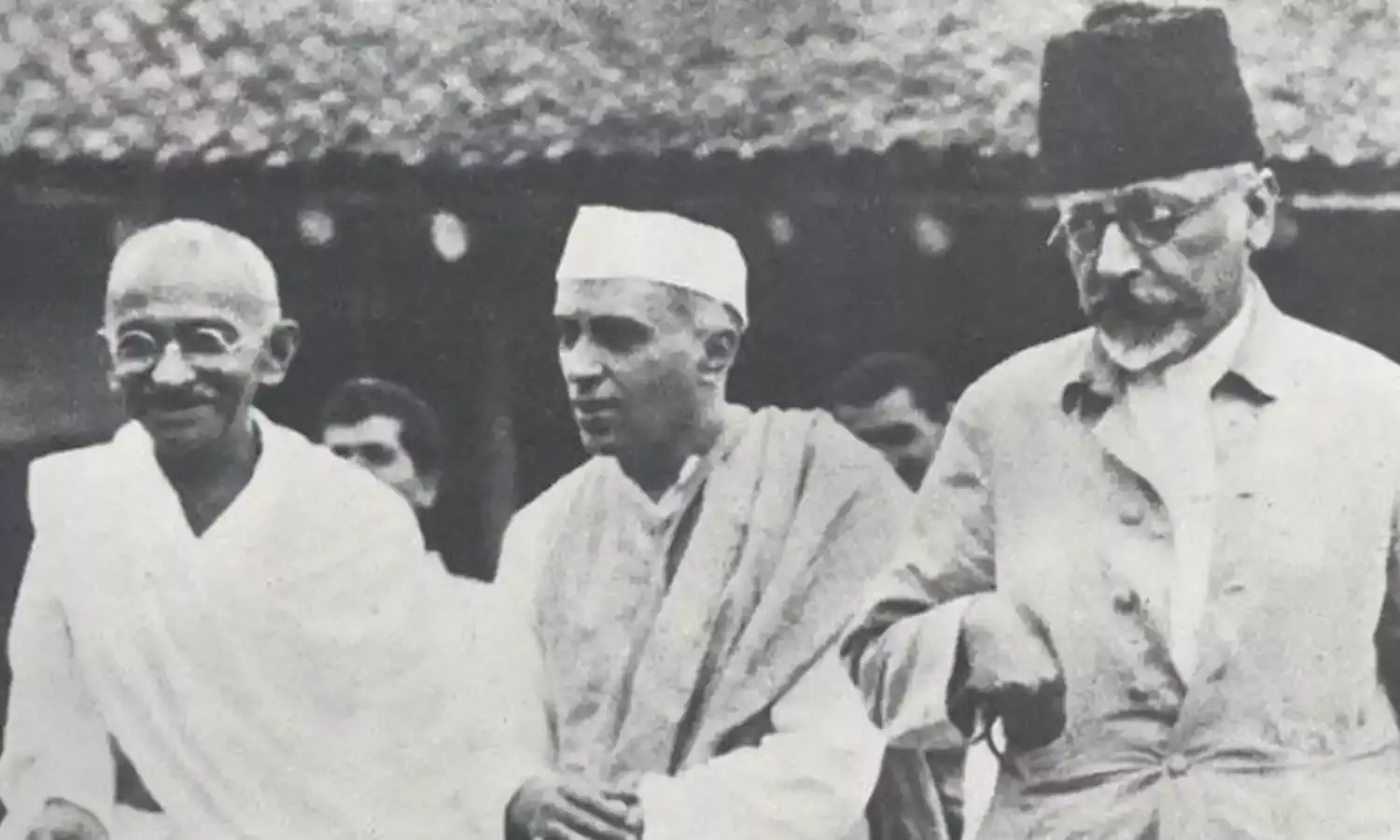

Often Gandhi is wrongly accused of having supported the partition of the country, whereas in reality it was people like the famous poet Iqbal and fundamentalist Hindus like Savarkar who made public pronouncements supporting the two-nation theory. So it is ironic that he should be questioned by the fundamentalist Hindus of today for not having undertaken a fast to prevent Partition. The fact is, the decision about partition was taken by Mountbatten, Nehru, Patel and Jinnah by marginalising Gandhi, and he was only informed of the decision as an accomplished fact.

Had Gandhi supported the idea of partition, why would he have chosen to remain absent from the ceremonies of the transfer of power from the British to India and Pakistan? When India was becoming independent, Gandhi was fasting in Noakhali to stop communal riots.

In fact, he realised and publicly expressed his frustration about people not heeding his advice of practising tolerance, non-violence and communal harmony. The only role he could play was to bring moral pressure on people to desist from communalist thought and violent action.

Gandhi undertook a fast in Delhi in January 1948 upon returning from Bengal. This fast was in support of minorities: Muslims in India and Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan.

Hindu fundamentalists were furious and tried to defame him by spreading the rumour that he was fasting to force the Indian government to give Rs.55 crores to Pakistan, which was actually due to them as part of an agreement with Mountbatten on dividing the assets of the government of undivided India, and it received a positive response from Muslims in India and Pakistan. He was hailed in Pakistan as the one man in both countries who was willing to sacrifice his life for Hindu-Muslim unity.

Some people say that Gandhi could not speak to Muslims in harsh terms as he could to Hindus, and hence practised Muslim appeasement. This is not true. During his fasts he convinced nationalist Muslims visiting him to condemn the treatment of minorities in Pakistan as un-Islamic and unethical. He beseeched Pakistan to put an end to all violence against minorities there, if it wanted the state in India to protect the rights of minorities here.

When some Muslims brought rusted arms as proof to him that they had given up violence, probably out of concern for him so he could give up his fast, he chastised them and asked them to cleanse their hearts instead.

Gandhi’s towering personality could contain communal violence to some extent. His assassination had a more dramatic impact and brought all such violence to an end. Sardar Patel’s ban on the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh also helped.

But four decades later, communal politics raised its fangs again when the Babri Masjid was demolished in Ayodhya. What has followed is a downward slide of the nation into communal frenzy.

For the first time a right-wing party practising outright communal politics is in power, with full majority at the centre and in most states of the country, and incidents of mob lynching of Muslims, their continuing marginalisation in social, economic and political life, and treating them as second-rate citizens, is the new normal.

Majoritarian thinking, which is contrary to the idea of democracy, dominates, and the minds of people have been communalised as never before in the history of the country.

Communal politics has brought out the worst in us.

It appears that the seed of communalism was buried in us. Probably the seeds of good and bad both are buried in us. The atmosphere in which we grow will determine which thinking will flower.

Communal politics in the post-Babri Masjid demolition era fanned communal thinking and it began to dominate. By this time the generation influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s ideas, and which had seen Gandhi in flesh and blood, was on its way out. Hence the thought and practice of communal harmony waned.

I was once invited by a respected gentleman belonging to the Jamaat-e-Islami for a meeting on communal harmony. I told him that if he was inviting me as a representative of the Hindu religion then he should rethink it as I was an atheist. He said that I need not come for the meeting. I argued that only an atheist can truly practise the concept of communal harmony, as one who is equidistant from all religions. Anybody practising a faith will always be more attached to their own.

It appears that we have not even given serious thought to what communal harmony is all about, and have paid only lip service to the idea. No wonder we have landed in such a messy situation today.