The Sidetracked Concept of Rural Industrialisation

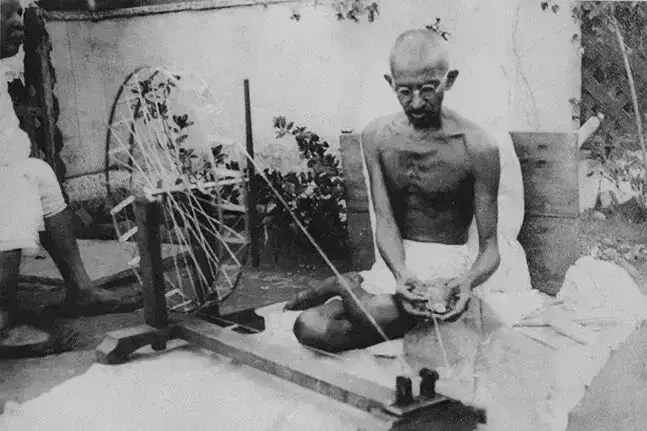

Gandhi’s charkha, swadeshi and gramodyog were motivations for rural development

Distressed framers, job seekers and their large number of family members who are voters in the country are now the focus of the national economic and political agenda. Parties in government or the opposition fronts are pointing out measures and demands to solve their problems and give the development process meaning and fresh momentum.

However these measures and demands are not foolproof, nor without any controversies, because the economic environment in our country is not basically formed so as to avoid any lacuna or controversy, or any discriminatory consequence. The situation demands some basic consideration for a foolproof effective economic policy and its implementation.

Each country in a global scenario has its own conditions and problems. These should be considered first while forming policy. There is no model formula which will be applicable to each and every part of the world. If an attempt is made to formulaically follow better developed countries, without considering the conditions specific to our own, more problems are created instead of being resolved.

India is basically a country with a network of lakhs of villages around cities, and agriculture is the main vocation in these villages, while most of the cities are industrialised and have a host of other sources of livelihood including manufacturing and the service industries. This is the current situation.

But immediately after Independence, the situation was different. Agriculture was the main activity for most Indians, and the cities were not so developed as to create opportunity for mobility from villages to cities. The farm sector was more self-sufficient, but clearly the need was to concentrate on villages for development in agriculture.

It is for this reason that Mahatma Gandhi appealed to the political leadership after Independence to turn to India’s villages, where most of India’s people still live and work.

This is the first realization: that agriculture needs development with allied activities in rural areas. The concepts of khadi (textile production) and gramodyog (village industries) were similarly motivations for rural development.

Nine years after Independence, in 1956 the government by an act of Parliament formed the Khadi and Village Industries Commission. A statutory body, the KVIC took over the work of the All India Khadi and Village Industries Board, with its head office in Delhi and six zonal offices in Delhi, Bhopal, Bangalore, Kolkata, Mumbai and Guwahati. It also has offices in all 29 states to oversee the implementation of its various programs.

The establishment of statewide boards for rural industries was an apt step for rural development. Small villages with fewer than 20,000 residents were considered for eligibility in about 114 schemes, for which capital support by way of seed money and other sources was guaranteed as per the statutory policy.

The industries expected to be started relate to natural resources like minerals and mines, forest and agricultural produce, chemicals and polymer units, engineering and solar-power based activities, and textile units, besides other activities like honey production and allied small enterprises.

The range of capital availability is between 25,000 and 25 lakh rupees, to be made available through banks, cooperative societies and banking consortiums. This scheme appears to be quite appropriate for the expected rural industrialisation along with agricultural production.

But despite clear policy directives, no positive picture seems to be emerging. There may be some figures available to show that something is done, no sign is visible of the expected rural development in various areas across the states. If all the schemes projected in the draft of development had been brought into practice, there would not have been such a crisis as is emerging today.

Why rural industrialisation, as planned under the draft of development of various state boards, did not actually materialise needs due analysis.

While policy is drafted by planners, its implementation rests with the bureaucracy. It is the bureaucracy which seems to be responsible for delays and lapses in implementing these schemes.

That rural youths are motivated to respond to the schemes should be a special prerogative of the field workers and bureaucrats, who need to create an atmosphere for entrepreneurs in rural areas to come forward with suitable schemes as per the scheduled norms.

As most units are either related to agriculture or the resources available in and around the villages, it is easy for those who want to earn more instead of relying on meagre incomes from farming operations.

But this does not seem to have happened on a considerable scale, with the result that farm distress is mounting gradually, leading to the present crisis.

The failure of bureaucracy in banking and government administration seems to have led to the failure of rural industrialisation. This points to the fact that our country needs a competent bureaucracy committed to development and willing to serve people, instead of trying to rule them as it was in the colonial era.

This concept of service needs to be first inculcated in the bureaucratic cadres at centre and state, as also in village governments and every district’s subregions and capitals. While people should be taught to be firm in their expectations, the elected MLAs and MPs should also try to tame the bureaucracy in the larger public interest.

The formation of the KVIC and the state boards followed the concept of rural industrialisation as preached by Mahatma Gandhi. His charkha and khadi and swadeshi concepts motivated the formation of the board.

We have failed to realise this vision due to the neglect of subsequent governments and bureaucrats, but it is based on the reality of our country. Gandhi was perhaps the first person to focus on what is India, and what should be done for rural development.