Silence is Not Consent, Inequity Is Not Closure

The Ayodhya verdict

The day justice is postulated on the same premise as elections- viz. that the preferences of the majority must prevail- is the day that democracy is doomed. The 9th of November, 2019 was perhaps such a day for us, for on this day the Supreme Court, inspite of accepting that the Babri Masjid had existed for 450 years and that the Muslims in Ayodhya had been wronged on multiple occasions, nonetheless ruled that the disputed site of the mosque should belong to the Hindu petitioners.

There are two ways to arrive at a decision. The first-and correct- is the deductive way: to collect the evidence, analyse it and arrive at a finding based on it. The second is the inductive way: to make up your mind first and then force, or induce, the interpretation of the evidence in the manner and direction that you want. The Ram Mandir order looks a lot like the second.

Consider some of the salient findings of the Court itself:

that the mosque had in fact existed at the site for more than 450 years, from 1528;

that the British intervened in 1857 when a dispute arose with the Hindus and erected railings to separate the worshippers of the two communities;

that there was no archaeological proof that there existed a Hindu temple below the site where the Babri Mosque was constructed;

that the ASI could not confirm that the underlying structure( whatever it was) had been demolished to construct the mosque;

that namaz was offered continuously at the site from 1857 to 1949;

that the Muslims were in fact " being obstructed from free and unimpeded access to the mosque for the purposes of offering namaz";

that it was on the night of December 16, 1949 that " exclusion of the Muslims from worship and possession took place" ;

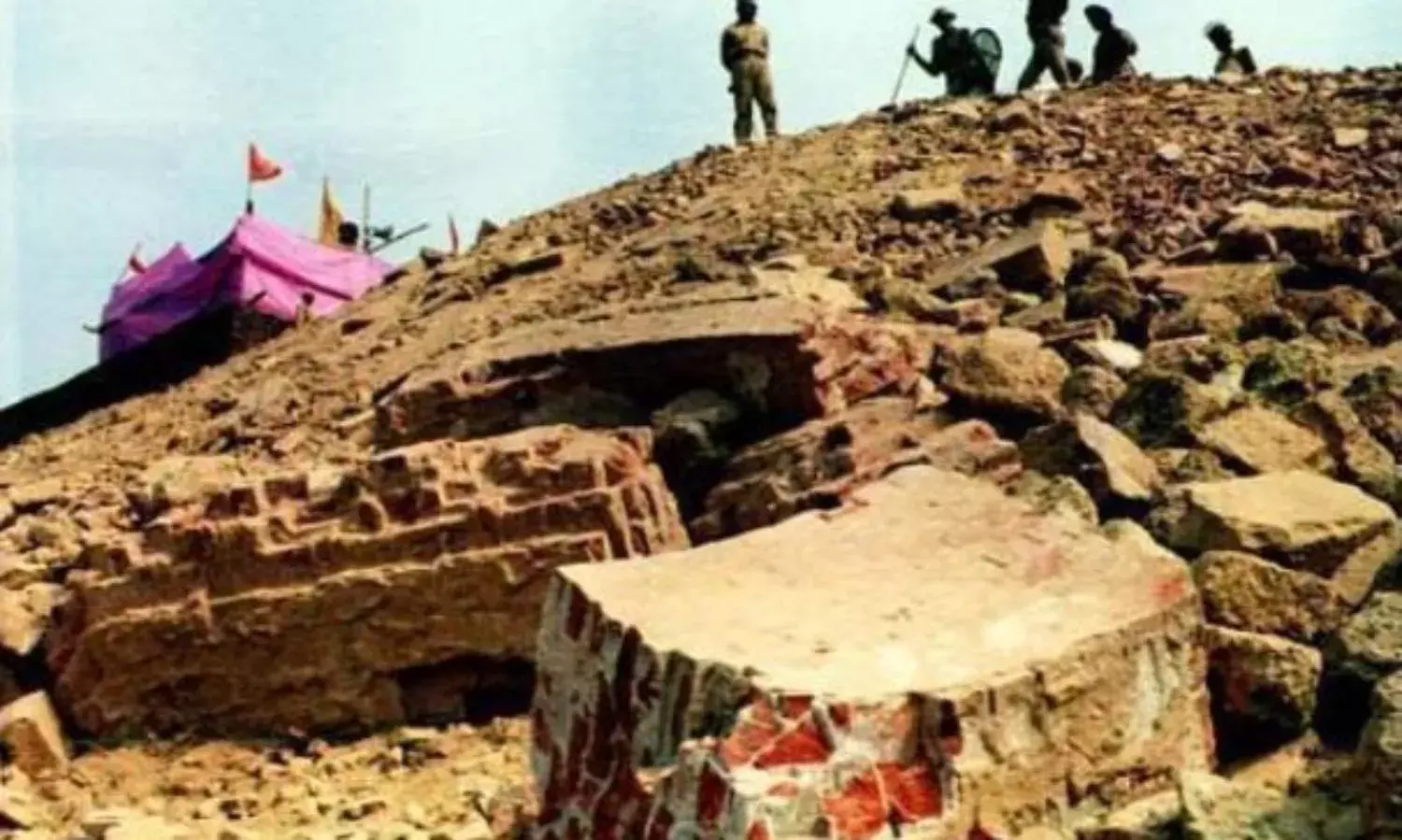

that the Muslim community had been wronged on at least four occasions in the past- in 1949 by the surreptitious installation of idols of Ram in the inner structure, in 1986 by the illegal opening of the gates to permit entry and worship by Hindus at the disputed site, in 1992 by the unlawful demolition of the mosque, and finally in 1993 by the making of a make-shift temple to Ram there, in complete violation of the law and an order of the Supreme Court.

This being admitted and accepted evidence, most objective students of law would find it difficult to comprehend the paraprosdokian finding that the Muslims were not in possession and that the site belongs to the Hindus.

The reason cited by the court is extremely ingenuous, viz. that the Muslim petitioners " have offered no evidence to indicate that they were in exclusive possession of the inner structure prior to 1857."

This just begs the counter: was there any evidence to the contrary? Isn't the ( admitted) existence of the mosque itself since 1528 enough to establish their claim? And here is the real shocker: the Hindu petitioners too could not offer any solid evidence of " exclusive possession" during the same period. But the rules appear to have been relaxed in their case: whereas the Muslims were required to provide hard evidence, for their adversaries the court generously accepted mere " preponderance of probabilities". Shorn of legalese this means unsubstantiated assumptions.

The fact that the judgement was unanimous, and that one judge even attached an addendum extolling the faith of the Hindus in Ram's birthplace, are indicators of the progressively constricting grip of religion over our institutions of governance. Analyst Apoorvananda in a recent article has termed it " unanimous majoritarianism."

An apt term which is bad enough in politics, but is a disaster in jurisprudence.

The Prime Minister has claimed that this is a new dawn for a new India and that we (read Muslims) should now move on. I wonder, would he have called it a new dawn if the judgement had gone the other way? And why is that the onus of moving on should always be with the minorities, and not with the remaining 80% of us?

Be that as it may, the Muslims have been largely silent (which is good) but the right wing ideologues and politicians are perhaps reading it wrongly as acceptance. For it is an acceptance under duress and born of a fatigue under the repeated onslaughts of the last five years: triple talaq, NRC, Citizenship bill, Kashmir and the apprehension of more in the pipeline- a Uniform Civil Code, calls for legislation to limit the number of children, and the referring of the Sabarimala issue to a constitutional bench which, make no mistake, is the thin end of the wedge to focus on other personal practices of their faith. Now that it appears to them that even the legal system is ranged against them, they have little choice but to be silent, but it is the silence of the graveyard.

There is no closure, either, as some of us would like to believe. In fact, this may just be a new beginning, not the bright new dawn the Prime Minister spoke about but a revitalised crusade for possession of the sites at Kashi Vishwanath, Mathura and other places where similar disputes have been lying quiescent, based on the same principles of faith and selective history as in the Ayodhya case. Even the Taj Mahal has been claimed to be a temple.

The disturbing portents are already visible: in the last round of mediations on the Ramjanam bhoomi, most of the Muslim parties had agreed to the site being handed over to the Hindu petitioners provided they relinquished their claims to these other sites, but the latter did not accept this condition. Nor has any BJP/ RSS/ VHP leader given this assurance post the 9th of November either.

And significantly, another Hindu outfit, the Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, one of the appellants in the apex court, has expressed their unhappiness at the decision to allot five acres of land for construction of a mosque in Ayodhya and stated that they are considering filing a review petition against this ( Indian Express, 13th November). These do not augur well for any closure.

Some analysts believe that the Places of Worship ( Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which prohibits the conversion of, or alteration of the status quo of, any religious place of worship as it stood on the 15th of August 1947, is adequate safeguard against any further re-possession attempts. But this is a naive mirage and pipe dream.

We should not forget that the Babri masjid was demolished in 1992, when this Act was very much in force, and in the face of an assurance given to the Supreme Court.

Secondly, as the Ramjanam Bhoomi judgement has shown, in today's India the law is subservient to faith, creative interpretation of history and brute political majority. And finally, it will take just one session of Parliament, or better still, an ordinance, to change the law, as Section 370 has chillingly demonstrated.

However well intentioned the apex court may have been in trying to do a balancing act in the Ayodhya case, the fact is that it has now tilted the scales of justice in favour of the majority community.

The inexorable mandate of politics was already ranged against the minority community, now even the courts have deserted them. This is not the kind of closure an enlightened democracy should be proud of.