How Bahujans Survived the Bubonic Plague in 1897

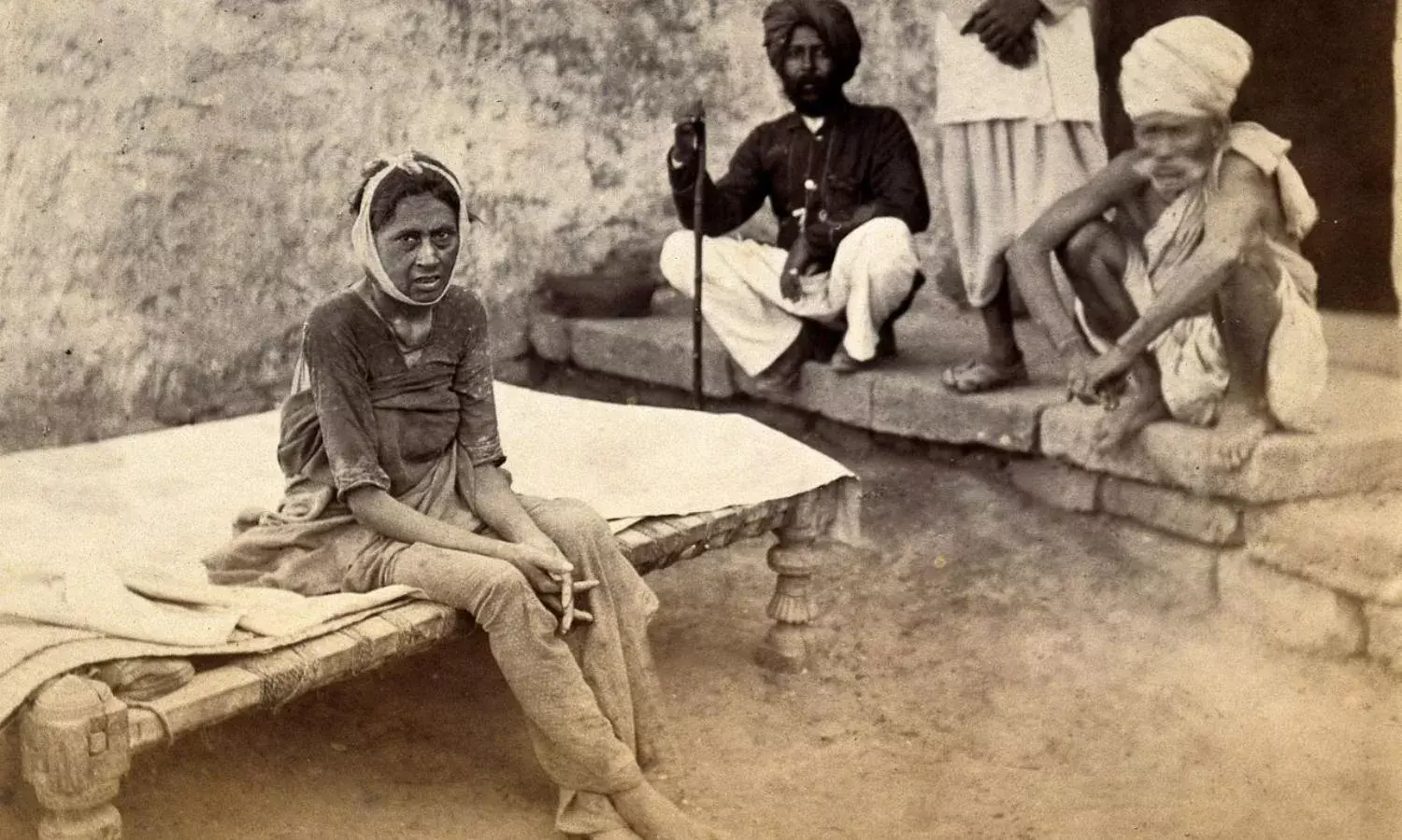

Memories of the black plague were still being discussed in my childhood and school days

Covid-19 has shaken the globalised world in a manner it never knew before. Having taken its birth in Wuhan, China its first attack focused on air conditioned travel life. Patient data in India so far shows that all those first phase Covid-19 positive persons were those who travelled by long-hour aircraft. The second line attack was on those working in long-hour air conditioned houses like software companies and other high-end offices, boardrooms and so on. To start with it has shaken the rich. But that does not mean it left the poor.

The fast spread of coronavirus happened because of massive international air travel that has expanded in the recent past, particularly after the IT industry boomed in the world. The theory that the ‘world is a global village’ has been proved more truly by the Covid impact than by any other means. In fact what happened was that the global high end economy made the world a global air conditioned city. This now has become a death trap with the novel coronavirus.

Just from January 1 to 20 some 40,000 people came to Hyderabad airport from America and Europe. People also came from many other countries and proved to be Covid-positive patients in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. One estimate is that 65,000 people landed at Hyderabad airport from all foreign air connections during this period. Some of those who came from Dubai, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore also proved to be Covid-positive.

The spread of Covid to 190 countries within three months of its surfacing tells a new story of globalisation.

Urban centres, mainly of large airport cities, became centres of more fear and anxiety. This gave rise to negative views of foreign air travelers and they became a source of fear and anxiety.

Indian villages are societies of social distance on their own, because of their agrarian and rural life. That seems to be something of a saving grace in this rapidly urbanising world.

How the world and India will get out of this pandemic is not certain, as medical science has yet to show a vaccine or exact treatment for Covid-19, though efforts are on.

The global panic and unusual measures like lockdowns worldwide force us to look back, to how India survived in 1897 a pandemic of bubonic plague that killed one crore Indians and 20 lakh people in China and other countries. A rough estimate is that at the time undivided India had a population of 18-20 crore people. It was in British colonial rule at the time and modern medicine had hardly entered the colony.

As I wrote elsewhere, Savitribai Phule and her adopted son Dr Yashvantharao died while treating and helping patients in Poona. Homeopathy and ayurveda hardly did any service to patients.

How did the remaining people save themselves and make India, Pakistan, Bangladesh what they are today? As of now we are 160 crore people put together. The information I could collect from the oral histories generations passed on in Warangal district of the present Telangana states makes an interesting story of the survival strategy of the masses.

When plague struck the urban locations they quickly realised through their common sense discussions to undertake social distancing through migration to forest and semi-forest areas where mass interaction could be totally avoided. Two caste communities could just pack and migrate to new and distant areas: shepherds, fishers and cattle herders. These communities could better survive in new areas on their own cattle and fish economy and forest produce.

123 years ago in Hyderabad Nizam state there was lot of forest and semi-forest land available for grazing animals and fishing resources along the rivers and streams. My grandparents along with hundreds of shepherd families were said to have migrated in that pandemic from Ursu, Karimabad (broadly known as Fort Warangal town, among the towns set up during Kakatiya rule from the 13th century onwards) to Pakala patte.

The Pakal lake which was built during the Kakatiya regime near Narsampet was a major water source to several settlers around the lake and streams it engendered. Mainly shepherds called Kuruma Gollas, fishers called Mutirajas and cattle herders called Lambadas migrated to the forest and semi-forest zones between Bahabubabad and Narsampet.

People of my age were the third generation in those migrant villages. The first migrants’ memories of the black plague were still being discussed in my childhood and school days. Several widows survived the plague as I was growing and they would tell the horrors of the plague, and their migration and settlement and survival.

Three of my grandmothers – Kancha Lingamma, my father’s mother, her elder sister Earamma, and my maternal grandmother Chitte Balakomuramma – were widows. Because of migration all three survived the plague. The two families settled in one place along the Pakal stream, which also was the forest zone for feeding goats and sheep, namely Papaiahpet.

My neighbouring family was of Kapu-Reddy who had two widowed women. In many critical situations the women survived more, because of the long age gap between wife and husband, and women’s better survival capacity. In many villages in that area there are many widows used to run families with all hardships.

They set up small hamlets and distanced themselves from urban and town or big village mass. They saved themselves at the cost of food scarcity by leaving their well built tiled homes in the urban settings. Their houses back in the original villages were occupied by others in those areas once the villages recovered from the plague and reequipped.

For a long time the migrants lived in small thatched homes. Their cattle economy has slowly grown and some families started podu (hand) cultivation also. In the beginning their main problem was the lack of availability of grain. They somehow managed with meat, milk, fish, forest fruits, roots and so on. Those who first escaped the pandemic slowly built up the cattle and agrarian economy. As their newly born began to grow they started building economies more rapidly.

That area is a tribal reserved parliamentary constituency as there are more small tribal villages in present day Mahabubabad district. It is also a very green belt of agrarian production with a lot of people living and working there.

Let us not forget that we in India built a population of 1.3 billion within 123 years of that pandemic. The Indian government is using the 1897 Epidemic Diseases Act now to tackle the 2020 Corona pandemic. With this experience we should not panic with Corona around us, but face it with confidence. We have very advanced medical sciences now. We shall overcome it.

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is a political theorist, social activist and author of many books, the latest being From Shepherd Boy to an Intellectual—My Memoirs.