Where Is My ‘Native’ After All?

After 75 years we are still asking who came to this land first

It was in the first grade during a sports period that I first heard the word “Bongal”. My friend and I sat balancing ourselves on the top of a structure in the sports field when I heard “ei bongal dutak namibo ko! (ask these Bengalis to get down)”.

I live in Assam, this is where I am rooted. When I travel I tell people I am from Assam. This often elicits responses such as “ah the Northeast” and “isn’t there a lot of violence?” or even “how did you travel to school growing up?”

Of hand disclosures that I am a Bengali Hindu upper caste Ciswoman born and brought up in Assam, bring out an altogether different commentary. One set of commentary is what I face when I am in Assam, another set is when I am in any other city in India. My experiences of ‘othering’ in Assam, which I experienced purely in reference to my linguistic and communal identity, is what I want to share with you.

What being Bengali in Assam and being identified as a ‘Bongal’, a term used to identify “Bengalis and outsiders” in Assam, means to me. I will try and explain what role the term ‘Bongal’ plays in Assam and how it is a form of othering.

It was 2001, my early years at school, when I heard the term Bongal at least once in a week. This was whenever any Bengali student took a seat which “wasn’t meant for us” in the school bus. I heard it whenever I tried to befriend anyone outside my community. When I sought friendship with an Assamese in school, they had to seriously consider if I was worthy of it. Over the years as I gained their confidence by proving our community’s stereotypes wrong, my Bengali identity faded into the background. I felt the pressure to fit in. I believed that I could acquire an identity by removing my ‘other’ identity. To this day, whenever I receive a call from my family when I am in a public place in Assam I make sure to speak in Assamese, or walk into a corner to speak in the most polished Bengali dialect.

After my class 10 exams, I moved to a convent school. There, I heard my community identity return during an argument with a close friend who said, “Bongal keitak trust e koribo nelage (these bengalis cannot be trusted).” To this day, my father hears the word Bongal hurled at him at his workplace once in a while.

I discovered the history of the word ‘Bongal’ only when I was living in Kolkata. I was telling a friend about my experiences of growing up as a Bengali in Assam. This friend of mine was a Malayali Christain born and brought up in a remote town in Madhya Pradesh. My friend, when asked “where are you from?” often answered saying “Oh! I am from many places.” He said it was to avoid being labelled by regional and linguistic identity because he felt he never quite connected with either of them. “Don’t fret too much about it,” he said, “they call us Mallu. Where do you think that came from?” This attitude may be an act of resistance on his part; a refusal to be categorised. It could also be his self-perception and seeing himself independent of the spatial/ethnic/racial/caste/class categorisation. Is this how he evaded everyday discrimination in India?

He told me that “mallu” comes from the Hindi word “mal” which means excreta. Many people say that it is only an innocent short form of the word Malayali. However, certain identifiers are hurtful to the one identified by it. Most ethnic slurs are difficult to locate etymologically. For instance, in many parts of the word ‘Bihari’ is used not only as a communal identity reference but also as an abuse. The word ‘Bihari’ means belonging from Bihar, a state in India, but at another level it is hurled at someone to insult them.

Identities, as such, get constituted as the ‘other’ and calling names is both a part of the process of othering as well as a by-product. But do we fight these identities? No, we don’t because in India the state fails to support us in the fight. Even until 2018, the Delhi High court asked the CBI to ascertain whether ‘Chinki’, a derogatory term used against those from the Northeast, has been notified as a casteist remark in the laws concerning scheduled castes and tribes.

Slurs have a serious psychological impact and are not “casual” ways to address people of a community. The fact that certain terms are banned from colloquial usage is because it induces intolerance towards “the others”. Individuals often feel threatened, while being referred to by their ethnic origin. One of the most critical discussions of the 21st century has been the removal of ethnic slurs from our vocabulary, especially in first world countries where political correctness would require awareness. Everyday contexts get sanitised with such legal proclamations. Their purpose is to recognize and find remedy for the problem but it hardly impacts individual behaviour.

When I came back to Guwahati after about five years in Kolkata, my mother convinced me that the cultural environment had changed. She said Guwahati now had a more metropolitan culture. That was the partial truth. In the next six months in Guwahati, I witnessed the NRC-CAA protests in December 2019 and lived in fear. Fear of damage, fear of being identified and a constant feeling of guilt of having been born in Assam.

The protest in response to NRC-CAA was not the first time Assam witnessed mass public riots on the issue of citizenship and immigrants. With a long legacy of inter-community conflict going back to Treaty of Yandaboo (1826), in 1951 NRC or National Register of Citizens was prepared for the first time in Assam. The issue of Bengalis in Assam and the question of nativity picked momentum after every few years, more strategically for political beneficence of a few.

Attacks on Bengali Hindus started in June 1960, when the District Magistrate of Guwahati and Deputy Inspector General of Police were stabbed. Bengali students in Assam Medical College, Dibrugarh Medical College and Guwahati University were forcibly expelled in the same month. I witnessed similar events when my neighbour, a student in Jorhat Engineering College, was asked to leave her hostel and faced verbal abuse during CAA protests.

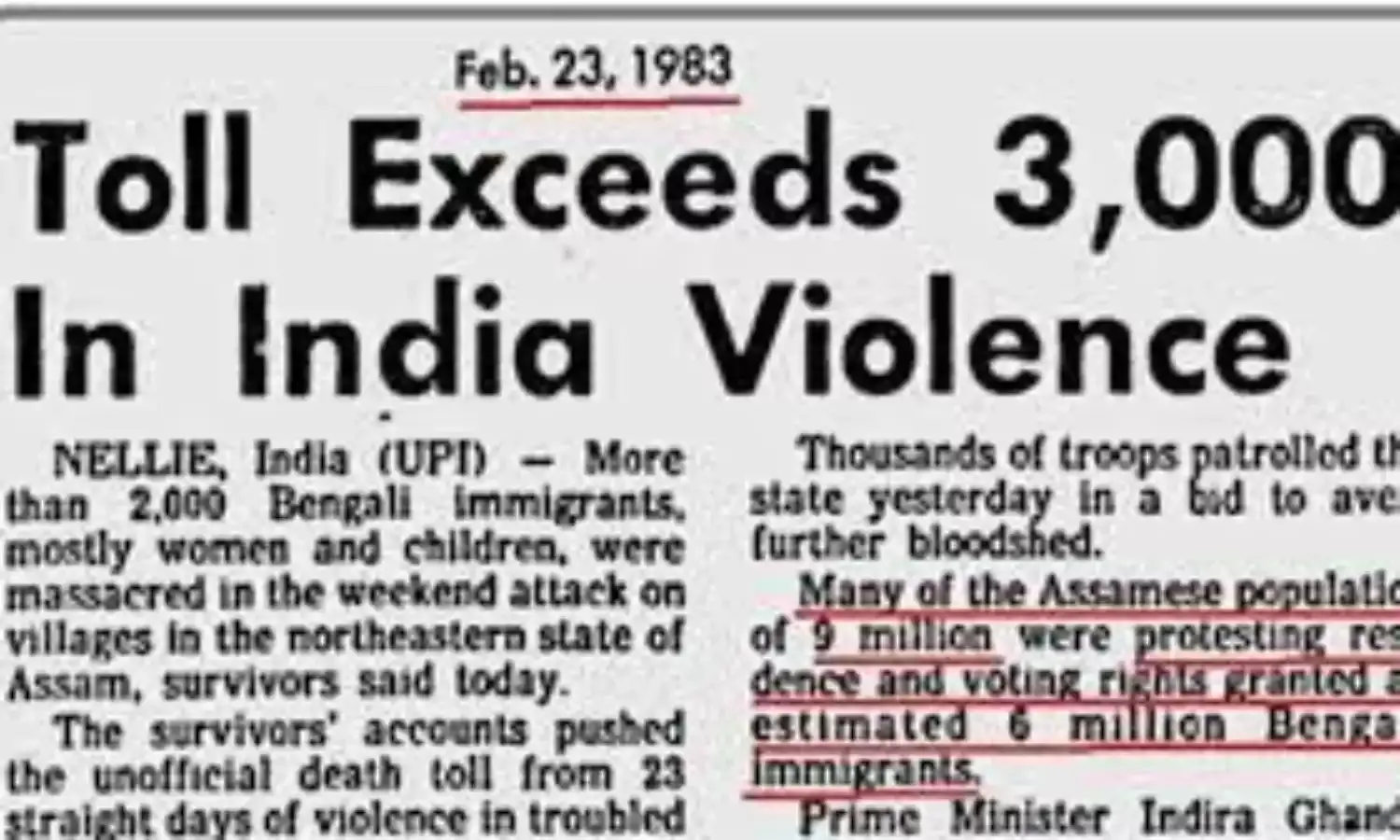

The Goreswar Massacre (July 3, 1960), North Kamrup massacre (January 3 1980), Mandwi massacre (June, 1980), Khoirabari massacre (February 7, 1983), Silapathar massacre (February 14, 1983) and Nellie massacre (February 18, 1983) – were some prominent attacks on Bengali Hindus in Assam, till the Assam Accord was signed on August 15 1985 between Union of India, Govt. of Assam, All Assam Student Union, and the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad. The Assam Accord, which was primarily created for the purpose of detection of foreigners, mandated March 24, 1971 as the cut-off date. Clause 5: “Foreigner’s Issue” and Clause 11: “Restricting acquisition of immovable property by foreigners,” were important.

After delays and occasional stirs on the issue, in 2014 the Supreme Court issued an order that NRC should be updated. In the same year Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came into power in Assam in alliance with the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) and declared that they will “deport all Bangladeshis from Assam.” The process of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was fast-tracked after the BJP regime took over in 2016.

Assam stood with the rest of the country in the protests against CAA, however, their reasons were different. Citizens resisted the Bill on the premise that it wasn’t secular and democratic but people in Assam resisted the Bill because its cut-off year was shifted to 2014. On December 11, 2019, section 144 was in place, and by 7pm a 24-hour internet ban was imposed. On December 13, 2019, thousands gathered at Chandmari Field for a two day civil disobedience. The workers of Assam Oil said that they would stop working.

The Guwahati Medical College and Hospital was left with the last three hours of Oxygen supply as protestors had allegedly destroyed the vehicle that delivered their Oxygen cylinder. Protestors across the state lamented, “what will become of us if Assam is populated with non-Assamese people? What will become of us; our culture; our language?”

Vehicles were pulled aside on NH-37 and if the drivers or passengers were Bengalis, they were pulled out of their cars and asked to chant “Joi Aai Axom!” All this went unreported by local news channels. The indigenous chanted in unison, on how Assam bore the brunt of immigrants from 1951 to 1971, which the other states did not, the CAA would prove to be beneficial in Assam for the Bengali Hindu refugees who they said were excluded from the NRC illegitimately. For the Hindus who were illegitimately excluded, providing legacy documents from 2014 and prior would be more accessible. While we are still seeing impact of the exclusionary bill, as Bengali speaking Muslims in Assam who are not included in the final NRC list continue to face the same fear, panic and humiliation. The crisis of Bengali Muslim’s citizenship needs redressal.

For most part, this alternative opinion was not well represented, as much as the protests were. The national media reported protests across the country and even those by Indians living abroad, but they also smoothed out the voice of dissent that came from many different corners. ‘No-CAA’ plaques and graffiti over the world and the country looked the same after all

There is always one side of any event that remains unheard. Growing up I had heard how my parents had lost one academic year in 1983 during the Assam Agitation. They slept at night fearing hand made bombs would be thrown into the yard. We heard similar rumours in 2019. Our apartment secretary called a meeting late one night and said maybe we need to take some personal safety measures as this area had a “concentration of Bengalis”. Though we convinced ourselves that our fear had taken the better of us; for most of Hindu upper caste population it isn’t everyday that you fear personal safety based on your community identity alone.

On December 22, 2019 my father received a Whatsapp forward supposedly written by Dr.Prashant Chatterjee, Associate Professor, Department of Bengali, Cotton University. “বাঙালীসকলৰ (হিন্দু) ওপৰত একাংশ অসমীয়াভাষী মানুহৰ ইমান খং কিয়?! কিয় বাৰেবাৰে অসমত বাঙালী বিদ্বেষী মনোভাব গা কৰি উঠে?! কিয় বাঙালী বাংলা ভাষা ক'লেই , এক ভাষিক বিপন্নতা অনুভব কৰে অসমীয়া সকলে?!! কিয় ইমান ঘৃণা, বিদ্বেষ, সন্দেহ!!?? Why is there so much anger towards the Bengalis (Hindu) by the Assamese? What causes the anti-Bengali sentiment in Assam? Why these feelings of misfortune prevail among the Assamese on the mention of Bengalis?)”

Dr.Prashant had worded his thoughts in Assamese as an urgent voice of the community that wasn’t speaking at all. The excerpt is from a longer message where he explained the history of Assamese-Bengali communal riots. As much as social media forwards seem like unreliable source of information, they are also the storehouse of emotions that wouldn’t find a space in the larger narrative.

Around the same time conversations started at my workplace too. There were elaborate intentional discussions in the cubicle adjacent to mine, on how “Bengalis are misers”, or they are “petty” and “Bengali music shouldn’t be played at Republic Day celebrations”. This took me back to class one at school. I felt small and wanted to disappear. I would hesitate to speak in Bengali. I have discussed this with my colleagues who expressed discomfort on this issue. Some felt confronted and asked “but I never do that to you, do I?”

No they don’t. Yet there exists an ‘us and them’. And why does the word feel so heavy to me that every time I hear it, my face feels burning hot and I feel nauseous?

I wish I could tell you, Bongal is a simplistic translation of being ‘Bengali’. Unfortunately, it has more historical and cultural context than any ethnic slur. A quick Google search will reveal that “Bongal” was originally a term used for Bengali Hindus in Assam, and eventually used for anyone labelled as outsider.The Britishers were called “Boga Bongal” (white foreigners) and Bengalis as “Kola Bongal” (black/dark foreigner). In 1872 a play titled “Bongal Bongalini”was written by Rudra Ram Bordoloi. It aimed to portray the “problem created by Bongals in Assam”. Assamese women who preferred to marry ‘Bongals’ were described as promiscuous women. Identification of Assamese women as such is indicative of suspicion with which Bengali men were looked at.

Asam Bandhu, a monthly that started in 1885, published a piece titled “Bongali” where the writer has equated the hill tribes such as Khamti, Singpho, Khasiya, Abor as well as “Bongals” with being ‘bideshi’ or an outsider, and as “uncivilised” and “impure”. The article stated, “besides the people of our land and those hill tribes all other people on this earth may be called ‘Bongal’. ... By the term ‘Bongal’ we mean filthy, impure people.”

The term has seen much usage including ‘Bongal Kheda’(Oust the Bengalis) movement. It is difficult to trace the exact number of usage of this term over the years. One can find memes, jokes, and posts on social media using the same key search word, mostly in local languages and a few in English. There are lengthy discussions on Quora on Arnab Goswami and blog posts, discussing if Dr. Samujjal Bhattacharya, Chief Advisor of All Assam Students Union is Bengali or Assamese. The fear is if a prominent figure from Assam has any Bengali links.

The fear of the ‘Other’ is far reaching and an every day event. “Who do you think would be sent across the border first?” or “There wouldn’t be clean bathrooms at the detention camps.” had become a dinner table joke in our family.

There is a habit amongst Bengalis who ask, “Desher bari kothae? (Where is your original home in your country?)” I have continued to answer Dhaka and Faridpur for most part of my life without knowing what Dhaka or Faridpur looks like. Neither my grandfather nor great-grandfather never went there, yet I am stuck with the identity of an outsider by default. The colloquial usage of the term is only a precipice of generational hatred towards a community that hasn’t quite evaded the public, cultural space.

I do not have a brutal tale to tell. Of what I experienced as othering. I am privileged enough to experience what one could call ‘milder’ form of it. I wonder at times if I was born into the other community in Assam, would I have resonated the same voices that prick me. Isn’t it human nature after all to protect one’s own and fight the other? How long would Assam take in the burden of outsiders? How long would they share their resources meant for the originals of the land?

If we change the parameters to measure development, it will get difficult to answer how far we have come in the last 75 years since Independence. On the platinum jubilee, as a citizen of the country I still have to fight to prove my authenticity. After 75 years we are still asking who came to this land first.

The problem of immigrants is a problem that we are facing across the world. However, it’s policy makers who need to develop an empathetic view of human lives. A humane lens across the world instead of a resource competition view of immigrants changes the dynamics at large. Othering, is only the by-product of the resource competition between native and outsiders. Policies can only protect lives at a macro level. The psychological consequences are what we least take into account while talking about this issue.

Jahnabi Mitra is a psychologist, and PhD research scholar at Ambedkar University Delhi. She she also taught at The Assam Royal Global University.