The Politics of Depoliticisation

Most political parties are in search of quick fixes to run their election campaigns

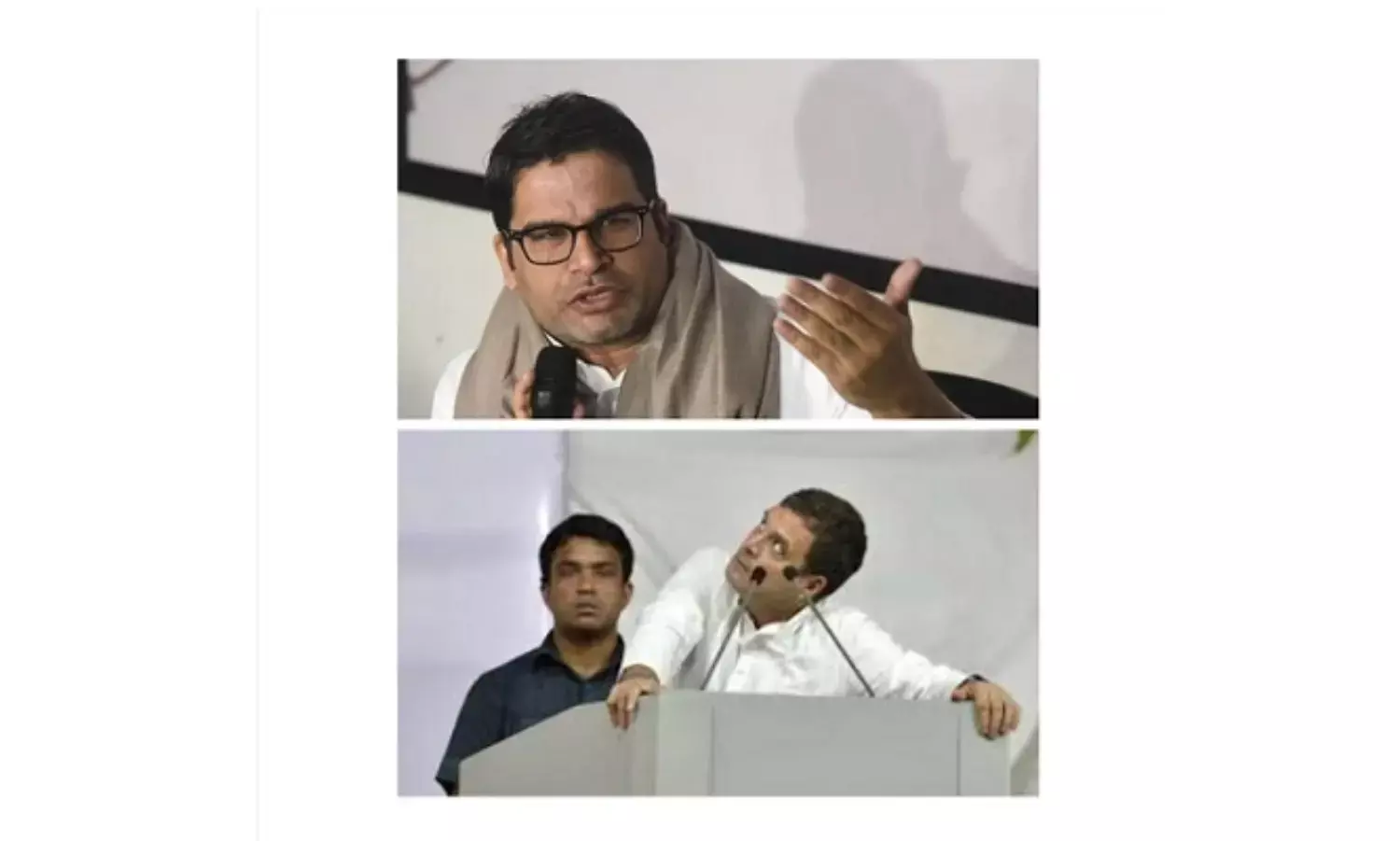

That the Congress party held six rounds of talks with a political consultant, and was planning to employ his services to restructure the party and galvanise its election campaign, reveals the marketisation of political parties in India, and the poverty of thought underlying it. The talks collapsed because senior leaders were unwilling to give him a free hand in running the party.

His joining the party might well have improved the party electoral fortunes, but would not have resolved the structural crisis facing it, which has to be addressed by its own leaders, members and cadres, and not by external agents or an election specialist. To think that any individual, no matter how talented he or she is, can magically change the fortunes of a party is disingenuous.

But this problem is not confined to the Congress party, most parties are in search of quick fixes to run their election campaigns. They have turned to election specialists, campaign organisers and spin doctors to help make the party more appealing to voters. This approach represents a politics of depoliticisation that drives so much of politics in India, as indeed in many other countries after economic liberalisation.

Contemporary democracy is unthinkable without political parties, but Indian parties are in bad shape in the absence of institutions that structure the distribution of power within parties and infrastructure in terms of its working offices, paid staff, and financial assets. They lack the organisational heft to exert a meaningful presence in politics between elections and in the everyday lives of citizens. Parties mobilise to contest and win elections but lately anti-BJP and non-BJP parties, with the exception of some regional parties, have not been very effective in this domain. Hence, the scramble to hire political consultants and professionalise election campaigns.

The BJP’s spectacular victory in the 2014 election was a watershed moment in this regard. It changed the nature of political communication and the professionalisation of campaign practices which other parties are trying to emulate and adopt.

However, reliance on election managers is problematic for several reasons. For a start, it bypasses the internal processes within parties giving primacy to feedback and information coming from external agents. This undermines party processes by building the campaign around the leader who doesn’t represent an ideology, but promises certain benefits from the state in addition to good governance. This can neutralise the ideological component of the party platform by short-circuiting its programmatic agenda.

There is no place for the street and no scope for political mobilisation and social movements in this framework. This emasculates politics and parties as networks and the underlying strength of their associated social linkages.

Political parties are undoubtedly the key building blocks of democratic elections and representative democracy. Only parties can provide coherence in large and heterogeneous electorates such as India’s by negotiating public preferences on a range of issues to build consensus. The negotiations surrounding it involve contradictory pulls and pressures but these form an integral part of party processes.

The consultant driven model of political management bypasses these processes replacing them with ideologically agnostic methods geared principally towards electioneering that can weaken the party system. The campaign template is a standard American style presidential template with outreach activities organised around the leader.

This template has been adopted by most political parties in India, barring the Left parties (which are organisationally strong but have proven to be unviable electorally beyond a few states) because most parties, as noted above, are organizationally weak and excessively personalistic. The wide ranging list of clients of political consultants from BJP, to Congress to regional parties testifies to their significance.

Their importance has been bolstered because stunning victories, like that of the All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) in West Bengal in 2021, are commonly attributed to the political consultant, while understating the role of leaders, parties and their labour in the electoral success of parties. Nonetheless, leaders find it convenient to outsource the work of mobilisation and communication to professionals.

The most important job of a politician is to understand and mobilise public opinion yet so many leaders are willing to hand over this core function to an external entity rather than letting party functionaries gauge the popular mood. Their replacement by the consultant and young marketing professionals signifies a major change in the way politics is conducted in India today.

The biggest challenge facing Opposition parties is the ruling party’s ideology and repressive policies but these issues are set aside in favour of the good governance agenda subsumed under the personal charisma of the leader.

However, successful election management cannot institutionalise the functioning of political parties be that of the Congress or any other party. Already suffering from weak institutional structures, parties will be further deinstitutionalized with election managers offering short-cuts on “How to Win Elections and Influence People”.

In the case of the Congress, it would neither create the institutional leadership mechanism for guiding the party nor help in reforming the party structure and empowering state units highlighted in recent discussions of much needed party reform. Basically, the Congress must create its own narrative and networks to propagate it.

The importance of wresting power from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at this juncture cannot be overstated and understandably Opposition leaders are looking for inputs to augment their winning potential, especially as they face a formidable political opponent which has limitless resources, media support and money power.

Nevertheless, this highly centralised model with the consultant working directly with the leader of the party and often taking decisions, not just on the campaign but also party organisation and even distribution of tickets will undermine parties and democracy in the long run. Political parties have to find ways of addressing fundamental organisational and ideological deficits of oppositional politics to safeguard substantive democracy. That process involves transcending identity politics to create a narrative of consequence beyond personalities, focusing on fighting communal hatred and neoliberal economics, to reacquire relevance, instead of relying on political consultants.

Zoya Hasan is Professor Emerita, Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University and Distinguished Professor, Council for Social Development, New Delhi.