When A Grave From The Past Linked Me To The Babri Masjid!

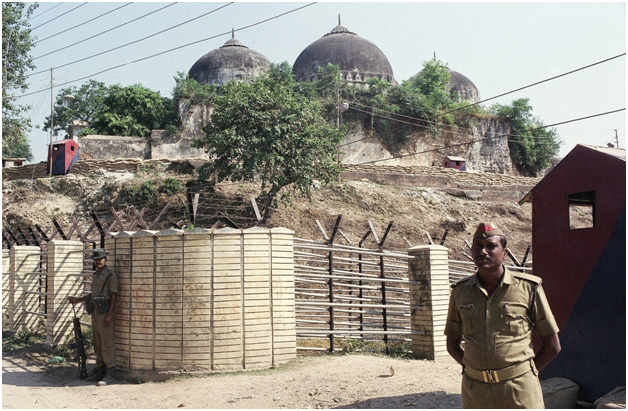

Security that failed to prevent the demolition of the Babri Masjid

Sometimes history comes out from nowhere and hits you in the face. And your skin breaks out in goosebumps as you try to digest the coincidences of time.

And so it was a few weeks ago, when a family discussion on ancestry had members googling for information that brought up facts, that were startling to say the least. As these established a link for me with the Babri Masjid that goes back into the graves of the 12th century and moved it from the political space into the personal. In a historical sense.

I had, like other journalists, covered the Ram Janambhoomi movement leading to the demolition of the Babri mosque on December 6,1992 in minute detail. And in the process had covered the decision of the then Kalyan Singh government to ‘lease’ 42.09 acres of the disputed land in Ayodhya to the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and the Ramjanambhoomi Nyas in what was even then a highly controversial decision.Despite directives to the contrary the Nyas and the VHP started pulling down a few small ancient temples on the land surrounding the Babri mosque, and a small Muslim graveyard located there. I visited Ayodhya to confirm and cover this. The graveyard stood on land owned by a Wakf, that lawyer AG Noorani later explained as “a trust in perpetuity in Muslim law, as enforced in India. The government had no title over it. Nor has the Nyas, still less the VHP.” I must confess I had little interest in the graveyard, even though it was visibly ancient, being interested in the politics of the issue and not the historical specifics.

Born and brought up in a fairly strict discipline, where lineage was personal and not for exploitation, as students one veered to the other extreme of ignoring this altogether to the point of complete ignorance. Life was all about what you as an individual made of it, and hence there was little room for lineage, dynasty, whatever in my life. Knowledge for me was limited to fairly immediate generations with a singular lack of interest in what had gone before except for a few immediate generations past.

About two weeks ago the discussion took us to the Kidwais, my maternal family. And we started speaking about the Kidwai’s, about Qazi Kidwa, the Seljuk Turk who had travelled the long way from the Sultanate of Rum in Turkey to this part of the world some time in the middle of the 12th century, who became a close associate of Sufi saint Moinuddin Chishti ( of Ajmer Dargah fame), and at his bidding travelled to Awadh and established what became his dynasty in Barabanki and adjoining villages. Qazi Kidwa was thus, the founder of the Kidwais who then spread through 52 villages of this area, the Sufi influence very visible to us even as children. Our family from Masauli threw itself into the freedom struggle with the Congress party, with Rafi Ahmad Kidwai in the lead. Land was sold to pay for the struggle, and all clothes and belongings that could be traced to British companies burnt in what we were told was a huge bonfire in Masauli.

During the discussion suddenly someone asked, and where did Qazi Kidwa die? Where indeed? And where was his grave? Everyone rushed to their computers, and suddenly we found articles, depositions in court long after the demolition of the mosque, pointing to the fact that one of the many graves that were destroyed in the graveyard adjoining the Babri Masjid, and part of its land, was that of Qazi Qidwa! That he had been buried there, date unknown, and his was one of the many old, decrepit, graves that were pulled down before the demolition of the mosque.

The Report of a delegation led by S.R. Bommai of Members of the Standing Committee of the National Integration Council (NIC) and MPs, to Ayodhya on April 7, 1992 found that the State government had "failed to fulfil the solemn assurances" given to the NIC. A letter of April 7, 1992 annexed to the Report (page 83) sets out the Muslims' claims and grievances in respect of the adjacent land. It said: "That on three sides of Babri Masjid exists an ancient graveyard over which existed thousands of graves, kaccha and pucca, including the grave of Qazi Qidwa. That scores of graves existed till recently which have been dismantled by the State government after 20th March, 1992, including the grave of Qazi Qidwa..."

Goosebumps as one was totally unprepared for this---to find that the founder of the Kidwais as it were had been buried on the land that has caused so much grief before and after the demolition of the mosque that of course came up beside the graveyard about two centuries later. And the thoughts naturally veered to the family, and the tolerance and secularism that had been part of our growing years. It was not a ‘western’ value as some ignorant people insist, it was a way of life for us where being a Muslim was as natural as being a Hindu or vice versa. And where religion did not interfere with secularism, rather strengthened it through belief and faith.

Rafi Ahmed Kidwai was a living example of it, through his struggle for independence, his opposition to the Muslim League and religion based politics, his own home where the dining table was always a composition of all religions, castes and creeds we are told, and his politics where he spoke his mind and into which he never carried his religion or his personal beliefs. His younger brother Shafi Ahmad Kidwai, married to my grandmother Anis Kidwai, was stabbed to death just before he was to leave Dehradun where he was the Collector during the violent days of Partition. His life was under threat, he was repeatedly urged by his family to come to the comparatively safer Lucknow, but he refused as he was in the midst of ensuring the departure of Muslims leaving the country for Pakistan, and settling in the waves of Hindu refugees after their long and often violent journey from Pakistan to Indian pastures. That he was killed we knew during our later years as students, but who killed him? This fact that in some families could have been used for generations to create hate, was moved out of the political realm altogether by Rafi Ahmed Kidwai and the young widow with three children (my mother being the eldest of the three), and placed firmly in the personal. The stabbing as it was explained to me later was part of the milieu of the times, the assailant probably out of control because of his own experiences and agony. Hence, while his loss was mourned and still is, it was never, ever given a dimension that could even remotely interfere with this family’s vision of India rooted in secularism.

Anis Kidwai herself was a living example of the secularism she so cherished. She was overcome with grief when her husband died, again facts revealed to us much later in life through her award winning book on Independence and Partition, and went to Gandhi to ask him what she could do. She started crying uncontrollably to which he asked her to go back, think what she could do, and from then on there was no looking back for this amazing women, with huge compassion and a will of iron. Clad in white khadi she and her two closest friends Subhadra Joshi and Mridula Sarabhai formed an indomitable team that set up camp in areas hit by communal violence, and worked to bring relief to the victims. Their faith in the Congress was shaken with the Emergency and shattered when the three decided to meet then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi about the family planning drive launched by Sanjay Gandhi, and were told by her with a dismissive, “aap log Sanjayji se miliye.” Anis Kidwai was a Rajya Sabha MP for two terms, and a strong voice for the pluralism of India. Her table in Windsor Place was always full, reflecting India’s composite culture. The residence had also become a haven for a number of young working women in Delhi those days who would drop by for a good meal, or just a feeling of being at home.

Anis Kidwai was a Muslim who said all her prayers, who observed the religious rituals but through her life taught us the meaning of secularism without even being aware of this. Perhaps my first lesson came from my mother, one of the first Muslim women to complete her Masters from Lucknow University at a time when she explained to me how all religions had their own rituals that might seem different but were the same as they had human beings, bound together by love and compassion, behind them; and true respect for one’s own religion came from full respect for the others. The house was always full of stories of exemplary secularism without any lessons being attached to these. Just a part of life.

A favourite was about how my father,in the Army at the time, was posted to Jammu in the midst of the post Partition violence. They were just married. He was asked to move to the front areas and had no choice but to leave his young wife alone in the two room set up they had been given. The landlord was a Sikh gentleman. Before leaving my father asked the landlord to look after her, and left. That night my mother heard people wailing and screaming in the building. She was terrified, and froze when she heard the sound of heavy footsteps on the staircase leading to her room. There was a knock on the door. She opened it quivering. And standing outside was the old Sikh gentleman who told her quietly that he had just come to see if she was fine, and to assure her that she was secure and should not worry. He then told her that their entire family on the way back from Pakistan had been killed!

This is what tolerance is, this is what secularism is. It is in the backbone of India. And while communal forces might have succeeded in destroying the heritage monument in Ayodhya on this day over two decades ago, and are bent upon wreaking havoc today, the resilience reflected in the resistance remains vibrant and strong.