India & Pakistan: Need to Make a False Dawn Real

NEW DELHI: The relationship with Pakistan remains India’s recurrent problem. Perpetually strained ties between the two countries complicate India’s foreign policy initiatives, especially in the neighbourhood.

Pakistan has always tried to maintain some sort of parity with its larger, more secure neighbour, to which end it has built up an exaggerated military establishment and put severe curbs on normal neighbourly exchanges. Its foreign policy has been focused above all on frustrating India. Occasional glimmers of more equable relations notwithstanding, the sub-continent has been an area of frequent strife and unending tension.

Yet it is not possible for the two countries to turn their backs on each other and walk away: contiguity and past associations are not to be ignored, and the incentive of finding a better way is always strong. These are simultaneous and conflicting realities that assail both countries and mean that the bilateral relationship was never smooth and has been subject to frequent breakdown.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s up-and-down handling of ties with the neighbour falls within a familiar pattern, where moments of hope lead only to disappointment and fresh initiatives peter out in rigid lockdown.

The Indian PM started off on a striking new note when he invited the Pakistan PM, among other regional leaders, to his swearing in. Nawaz Sharif came as did the others, and their presence seemed to proclaim that a new, more hopeful era in the sub-continent was at hand. But it was a short-lived expectation, and before long the ancient hostilities resurfaced to banish any early prospect of change.

Since then, there have been many shifts of mood and sentiment, and the initial promise remains unfulfilled. In Pakistan there is a plethora of actors who come out against better relations, some openly hostile, others, more ominously, with covert support from state agencies, all hell-bent on frustrating any effort to reduce mistrust, so we return time and again to the angry exchanges that tend to characterize this relationship.

Though circumstances are seldom propitious, some leaders have nevertheless been bold enough to take the initiative in trying to improve Indo-Pak ties, which is the most sensitive of foreign policy issues. Indeed, on the whole India’s leaders have not been averse to seeking a way forward, which implies readiness for a measure of mutual compromise. The strong rhetoric and unbending demands of political leaders when in opposition tend to be moderated by the realities of power once they assume office.

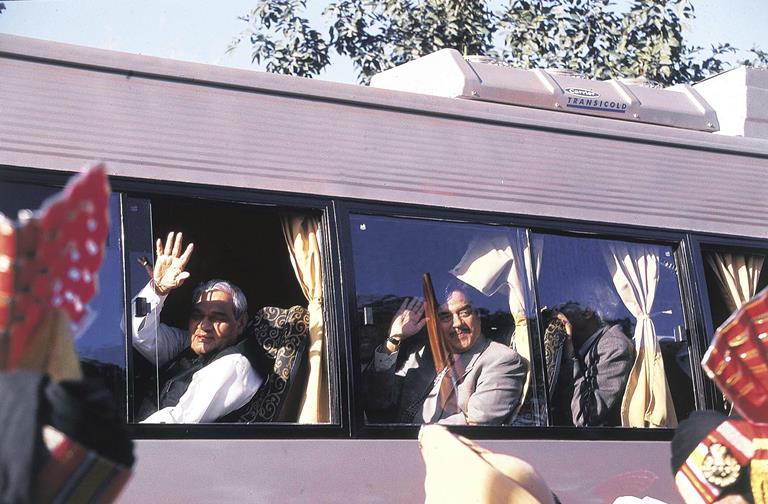

Former PM Atal Behari Vajpayee is a case in point: he was regarded as a firebrand nationalist, identified with a strong security policy that left little room for discussion or conciliation. Yet it was Vajpayee who made the dramatic bus journey to Lahore that is still the benchmark for friendly outreach to the other side.

PM Modi, with a no less hardline image, has been equally ready to take the initiative, including a surprise visit to Lahore. The results of his efforts are rather mixed but indifferent achievement has not been permitted to shut down the process of dialogue. Some observers believe that better results can be achieved by tough-minded leaders rather than by the more moderate ones, for if concessions are to be made and compromises sought, that is more readily done by strong leaders, especially if they enjoy good parliamentary support.

This argument is often heard but it cannot be substantiated beyond a point, for much depends on the circumstances and on the individual judgment of the person in authority. When I.K.Gujral was Prime Minister he was able to establish a process of dialogue that is relevant even today, and this despite the extreme vulnerability of his parliamentary position. He also enunciated the ‘Gujral Doctrine’ that had a beneficial impact on the affairs of the sub-continent and laid down markers of good neighbourliness that have not lost their significance.

The Prime Minister has been criticized for his uncertain course vis-à-vis Pakistan, reaching out one day but lowering the shutters immediately thereafter. Certainly there has been plenty of stop-go in his dealings with Pakistan, but in fact PM Modi’s way has been in essence no more variable than that of the long line of his predecessors.

The Indo-Pak relationship is highly accident-prone and leaders are all too often confronted by deliberate incidents intended to promote open hostility. Dealing with such incidents against a background of aroused public opinion is a big challenge, and there has been no recent letup even while both Prime Ministers are seen to be trying to promote more constructive discourse.

Deliberate spoiling tactics by some elements have tended to ensure that relations should never settle down but there are some recent shifts in perception that are worth noting. Some ‘out-of-box’ thinking in Pakistan tends to acknowledge that India has now pulled well ahead and that in its own interest Islamabad needs a change of tack in its India policy. Rather than maintain unending confrontation, the argument runs, there is advantage in coming to at least a limited settlement with India, to benefit from its economic advance and make it a partner rather than a perpetual rival.

Such ideas are as yet no more than the aspirations of an enlightened few and do not have any real impact on policy making, but nevertheless they are worth noting as symptoms of possible change.

The insuperable complication is terror. India has been the victim of repeated acts of terrorism from Pakistani territory, and there are many extremist groups whose main purpose is to foment terror and send bands of trained attackers against targets in India. The list of such attacks is long and their impact has ensured that relations cannot but be seriously disturbed. The recent incident at Pathankot is the latest setback and has had the effect, as have many previous incidents, of bringing a halt to dialogue and other peacemaking activity. Although Pakistan has always denied responsibility, its denials lack credibility, not in India alone but in the eyes of observers all over the world. Moreover, it is known that some of the groups operate with the tacit if not the overt support of military and security agencies and thus remain immune from all attempts to bring them under control.

This strategy for keeping India off balance has achieved little but has cost Pakistan dearly, both in terms of its international standing and, more crucially, in unloosing murderous fanatics on its own people. Pakistani interlocutors point out, correctly, that their country is the biggest victim of its home-bred terrorism, but that has not motivated them to take the obvious measures required to bring these elements to heel. It is galling for India to see identified terrorists walking free in Pakistan and, worse, inciting more attacks on India. This ultimately is what has nullified every effort to improve matters between the two countries.

Yet there are occasional indications that things could take a turn for the better. The Pakistani public has been so appalled by the calculated terror attacks on its own people that it has demanded action from a formerly quiescent government. The armed forces have been directed to go after the criminals in the remote locations that were their safe havens.

A change of approach is also visible in the somewhat more responsive Pakistani reaction to Indian concerns after the Pathankot attack. India has also acknowledged receiving information from the Pakistan NSA that helped stave off a planned terror attack on targets in India. These may be modest steps thus far but they bespeak better intentions and greater willingness to make common cause on this all-important matter of terrorism.

Nor should one ignore the outcome of the back channel talks on Kashmir of a few months ago where representatives of the two sides came close to finding a mutually acceptable course on this most divisive of issues. Neither government has shown keenness to follow up what their representatives laboriously put together in the back channel, perhaps because of the change of guard in both capitals, but nevertheless the back channel delivered remarkable results which will surely be retraced when the time comes for top-level consideration of the matter.

For now, it is noteworthy that the two sides did not buckle under after the Pathankot incident. The perpetrators may have expected a much more disruptive response that would effectively nullify all efforts to improve relations. But the governments kept their composure and reacted with considerable restraint, with the result that a certain measure of cooperation has been able to develop.

Where this could lead is impossible to say: there have been a number of false dawns in Indo-Pak affairs, and a moment of control in the face of provocation is no guarantee of future restraint: we will have to wait and see.

Until then, we can welcome, as a possible harbinger of better ties, what has been announced of cooperation between the NSAs of the two sides in responding to a dangerous security challenge to India that was brewing across the border in Pakistan.

(Salman Haider is a former Foreign Secretary who was instrumental in establishing the composite dialogue with Pakistan)

(File Photograph: Former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee on the bus to Lahore)