Even Narendra Modi's One Man Rule Cannot Bring in the Emergency

Some harshest mistakes have been mollified by straight repentance by the perpetrators. The post-war Germany apologized for the atrocities committed by Hitler and even paid the reparations. Not that the sins committed were forgiven but people generally felt that the children and grandchildren of their parents and grandparents have tried to make amends.

Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh went to the Golden Temple at Amritsar to say sorry for Operation Bluestar when the Indian army stormed the temple to kill the militants, including Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. The state could not allow another state to come in the country.

But the emergency, which was no less a crime, till date remains the darkest phase and not even a word of sorry has come from the Congress party, particularly the dynasty. The non-Congress parties off and on issue statements or hold protests. But the Congress party, which was ruling then, remains conspicuous by its silence.

After all, what provoked the emergency? It was the Allahabad High Court judgment which unseated then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi for a poll offence. Instead of following the court’s verdict, she abolished even the rights of the judiciary to question such orders by suspending the very constitution which authorize the courts to assess the rights and wrongs.

Had Indira Gandhi resigned—her initial decision to step down which was strongly opposed by Jagjivan Ram—and gone to be public to seek forgiveness she could have come with a thumping majority. People were angry by the excesses she committed during the emergency and the way in which she had become an autocrat.

Although her son, Sanjay Gandhi and his alter ego Bansi Lal ran the state as their personal fiefdom and brooked no criticism, she was generally seen as someone who was innocent and oblivious to what was happening. In fact, things had come to such a pass that blank warrants had been issued to the police who used the warrants to settle even their personal score.

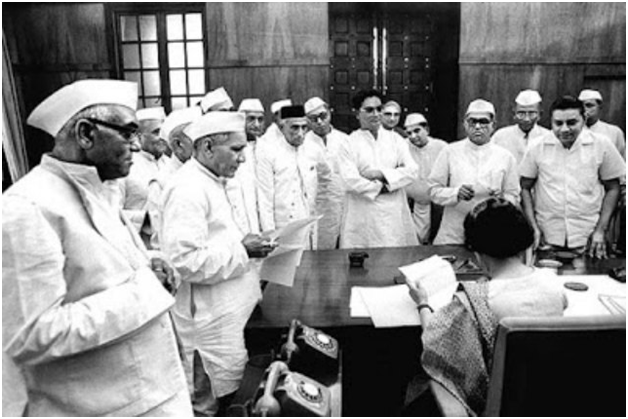

As a result, more than 100,000 people were detained without trials, houses and business premises of opponents, including political leaders, were raided and even an innocuous film, Aandi, which portrayed an autocrat ruler, was banned because it had some resemblance to Indira Gandhi’s role.

If I were to explain the emergency to today’s generation, I would repeat the adage that eternal vigilance is required to defend the press freedom, which is as much truer today as it was when India won freedom some 69 years ago. Never did anyone expect that a prime minister, after the high court’s indictment, would suspend the constitution when she should have stepped down voluntarily.

Former Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri would often advise his colleagues: Sit light, not tight. That is the reason why he resigned as the railway minister after a big accident at Ariyalur in Tamil Nadu. He took moral responsibility for what had happened.

It is difficult to imagine anybody following that precedent today. Yet, India is still looked upon by the world as a country where the value system exists. Parochialism or posh living is not the answer. The country has to go back to what Mahatma Gandhi told the nation: Disparities drove people to desperation.

There is noa point in harking back on the days of independence struggle. All had joined hands to oust the British. I wish the same spirit could be revived to oust poverty. Otherwise, the independence comes to mean a better life only for the haves.

If there was one-person rule of Indira Gandhi a few decades ago, today it is that of Narendra Modi. Most newspapers and television channels have adapted themselves to his way of working, if not thinking, as they had done during Mrs Gandhi’s period.

The one-man rule of Narendra Modi becomes ominous in the sense that no cabinet minister counts in the BJP government and the joint consultation by the cabinet is only on paper. All political parties should put their heads together to stall any emergency-like rule before it actually comes to exist. But even a person like Arun Jaitley who knows the rigours of the emergency—he too was jailed—would not fall in line because his way of thinking doesn’t seem to be dictated by the RSS.

I do not think that the emergency will be re-imposed because the amendments incorporated in the constitution by the Janata government makes it impossible. Yet, conditions can be created which will suggest the emergency without a legal sanction. However, public opinion has become strong that such a step is not possible. Even people may come out on streets to protest against any rule which is autocratic and resembles the emergency.

Basically, what counts is the strength of the institutions. Even though they have not regained the health which they enjoyed before the emergency, the institutions are still strong enough to resist any move which even remotely restricts their freedom. There are recent examples which evoke that kind of optimism. Take the case of Uttarakhand. The house was dissolved one day before the floor test of the members. The Supreme Court held the governor’s order ultra vires and revived the Assembly. Even a state high court like the one in Maharashtra has admonished the Censor Board not to act like a grandmother but to stick to its job of certification rather than imposing cuts. Only one cut was allowed by the court as against as many as 90 suggested by the Censor Board.

This example should give heart to the critics that conditions are improving and may soon get the same vigour which they enjoyed before the emergency. No ruler would dare to repeat what Indira Gandhi had done but uphold the constitution in letter and spirit. The lessons learnt from the emergency would not have been lost and there would be the same old confidence in the public that their freedom was not fettered and their right to differ in any way curtailed.