'The Work of Journalists Is to Interrupt Frenzy, Not Feed It'

SINGAPORE: The surgical strikes carried out by India at the Line of Control (LoC) with Pakistan in the backdrop of the terrorist attack in Uri have fanned social media passions in India and Pakistan.

The social media on both sides is rife with chest thumping nationalist calls for war, for teaching the enemy a lesson.

In the shared languages of the two countries, Hindi and Urdu, barbs and insults are flying fast on the social media.

A digital war is already being waged on Facebook pages and twitter feeds, drawing up deep-seated emotions of hatred, recalling old histories of wars fought and won, superimposing these histories with each nation’s version.

Twitter hashtags have already declared war, celebrating the victories of the Indian army, tweeting the power and the skills of the army in scripts that resemble Bollywood stories.

Pakistani artists have been banned from Bollywood and packed back to Pakistan.

Indians have quickly declared that the rivers arising from India and supplying water to Pakistan must be dammed.

Social media trolls have once again declared as anti-national all those calling for dialogue and peace. YouTube videos using vile language differentiating between nationalists and traitors are floating through my screens, threatening to unleash violence on anti-nationals.

Mainstream media and nationalism

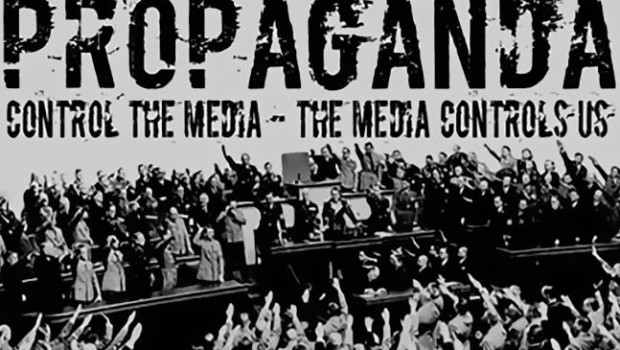

For the mainstream media that is already jingoistic in its nationalist fervor, calls to war are natural extensions of the nationalist sentiment.

As the 24-7 news channels spin out calls for avenge, for now being the time for unquestioned patriotism, playing again and again the rolls capturing army battalions, artillery, and army vans, and airing military experts calling for war, critical questions are suspended.

What is a surgical strike? What is the plausibility of a surgical strike? What is the legitimacy of a narrative of surgical strike? What was the magnitude of the surgical strike? What was the level of terror threat addressed by the surgical strike? How was this surgical strike different from earlier operations in the region? Why did the government follow the strategy of publicizing the strike? These questions remain unasked.

Conversations seamlessly shift to the necessity of war for geosecurity, oblivious to the nuclear threats and the risks to human health and wellbeing to populations in both countries posed by war. Conversations uncritically celebrate the precision and might of the Indian military operation.

On the other side of the border, similar propaganda is being carried out in denying that there was an operation carried out by the Indian army, inviting international journalists to cover staged narratives.

The aggressive statements made by Defence Ministers on both sides are uncritically hyped up in televised provocations.

The media stories cooking up the hysteria of public opinion drive their TRP ratings by speaking to the unfiltered raw emotion of nationalism. The coming together of the public around the war is also a market opportunity for large audience numbers glued to television sets and smartphone screens.

Also, the narratives of war, surgical strikes, and terror operations work well to boost the image of a government that is performing poorly in the domestic front.

Failures of journalism

In their quick calls to action, the stories fail to practice the basics of good journalism.

Critical questions about the veracity of the claims of the surgical operation, the supporting evidence, and the underlying logics remain unasked. Critical questions about the exact nature and scope of the operation remain un-interrogated, instead circulating ratings-grabbing headlines that scroll across the screen.

For instance, what is the evidence to document that the strike actually addressed the terror threats? What were the levels of terror threats that were addressed?

These questions ought to give pause, suggest moments of reflection that interrupt the continual churning of jingoistic headlines.

When media sell themselves to performing the propaganda function of the government, driven by a narrow market rationality, the suspension of such critical questions is naturalized as a necessity for nationalism.

Even more, journalists asking such questions are quickly labeled as anti-national, hounded by trolls on social media.

Evidence and media

Wars have enormous consequences on both civilians and armies. Therefore, media have key responsibilities in asking for evidence in the backdrop of overarching public narratives of war.

U.S. journalists failed to interrogate the state propaganda escalating up to Operation Iraqi Freedom. This failure of basic journalism created the grounds for massive instability that continues to haunt the globe.

The failure to ask for evidence and to critically examine the evidence make way for unquestioned and uninterrupted state power with mostly negative consequences for democracies.

The work now and the months ahead for journalists reporting on/in India is to critically examine evidence, to bring out the subtleties and nuances that are much necessary in disrupting the manufactured images of binaries in propaganda messages. The work of journalists is to interrupt the social media frenzy, not feed it.

A Washington Post report published on October 2, based on interviews with Kashmiris on the other side of the border suggests that there was no evidence of Indian army crossing into the other side of the border.

While it is entirely possible that these forms of evidence are themselves manufactured or staged, the only way to have a sense of what happened is to dig deeper for evidence.

Rather than discounting these pieces of evidence, journalists in India ought to critically engage with them. More importantly, they ought to seek out the voices from Kashmir, from the sites of the war.

Incapable of performing their destined role as the fourth estate, the media have turned into propaganda machines for war. For some of these media sources, unchecked stories floating on Hindutva blogs become the source of information. Rather than performing their roles as critical interrogators of power, these media have become the very tools of power.

Dialogue and the role of the media

As recent wars launched across the globe point clearly, wars leave no winners except the politicians that seek to legitimize their power through the hysteria generated by wars and the military-industrial complex that profits from wars.

For everyday citizens, as we witness in Punjab in the last few days, wars are threats of displacement, of being uprooted from ways of life. For the jawans in the army, mostly from the disenfranchised segments of society, wars are threats to life.

The media has an important role to play in giving us pause when the climate of public opinion bays for blood.

Media has an important role to play in presenting the many sides of war, in bringing to life stories and (im)possibilities that otherwise remain erased in binary narratives.

In presenting nuances, the media invites us to examine our closely held beliefs. Media invites dialogues that cause us to reflect on our deeply held beliefs. Such is the power of the media when it performs its role as the fourth estate.

(Mohan J.Dutta is Provost’s Chair ProfessorHead, Department of Communications and New MediaDirector, Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE))