Taliban Finally Confirms Mullah Omar's Death, Differs On Details

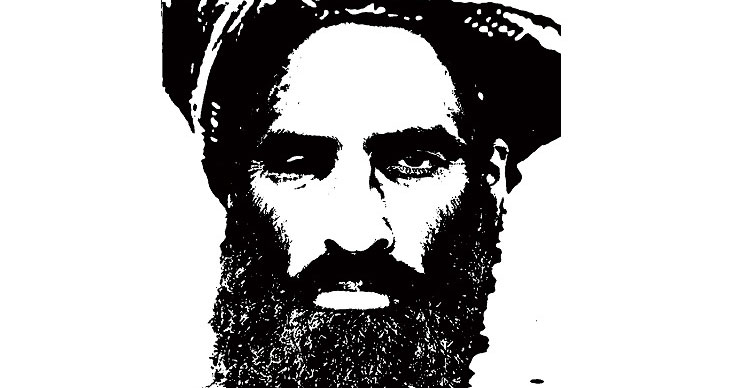

Mullah Omar

NEW DELHI: The Afghan Taliban on Thursday confirmed that Mullah Omar -- the group’s elusive leader -- is dead. A statement issued by the group states, “his [Mullah Omar's] health condition deteriorated in the last two weeks,” citing the cause of death as “sickness.” “The leadership of the Islamic Emirate and the family of Mullah Omar... announce that leader Mullah Omar died due to a sickness,” the Taliban statement said.

The statement follows reports quoting Afghan government officials on Omar’s death, with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s office saying that it believed "based on credible information" that Mullah Omar died in April 2013 in Karachi. A spokesperson for Afghanistan's National Directorate of Security, Abdul Hassib Sediqi, reiterated the above, saying, “We confirm officially that he is dead.” "He was very sick in a Karachi hospital and died suspiciously there," Sediqi said.

The Taliban statement referred directly to the above reports, saying that “not for a single day did he [Omar] go to Pakistan.”

Mullah Omar’s death deals a severe blow to the Taliban, removing a unified figure at a time that the group is riddled with factions -- especially over the prospect of talks with the Afghan government.

In fact, the news of the Taliban leader’s death comes just a few days before a second round of peace talks between the government and negotiators claiming to represent the Taliban. It also follows an interesting statement issued by the Taliban in mid July, where Mullah Omar gave his approval to the peace process.

In his (and here a caveat must be added indicating that there is no way to confirm whether the statement was issued by Omar himself) first comments on the talks that aim to end Afghanistan’s 13 year war, the Taliban chief hailed the process as “legitimate.”

“If we look into our religious regulations, we can find that meetings and even peaceful interactions with the enemies is not prohibited,” the reclusive leader said on Wednesday, in his annual message on the eve of Eid ul Fitr. “Concurrently with armed jihad, political endeavours and peaceful pathways for achieving these sacred goals is a legitimate Islamic principle.”

“As our holy leader, the beloved Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him), was actively engaged in fighting the infidels in the fields of ‘Badr’ and ‘Khyber’, he simultaneously participated in agreements beneficial for Muslims, held meetings with envoys of infidels, sent messages and delegations to them and on various occasions even undertook the policy of face to face talks with warring infidel parties. If we look into our religious regulations, we can find that meetings and even peaceful interactions with the enemies is not prohibited but what is unlawful is to deviate from the lofty ideals of Islam and to violate religious decrees.”

“Therefore the objective behind our political endeavors as well as contacts and interactions with countries of the world and our own Afghans is to bring an end to the occupation and to establish an independent Islamic system in our country. It is our legitimate right to utilize all legal pathways because being an organized and liable setup, we are responsible to our masses, we are an integral part of human society and rely upon one another. All Mujahidin and countrymen should be confident that in this process, I will unwaveringly defend our legal rights and viewpoint everywhere. We have established a ‘Political Office’ for political affairs, entrusted with the responsibility of monitoring and conducting all political activities,” the statement -- posted on the Taliban’s official website -- reads.

The statement was seen as crucial as it seemed to address concerns that the peace dialogue did not have the backing of the leadership.

The talks, although at a very initial stage, have seen some progress, with an Afghan delegation arriving in Islamabad to talk to the Taliban representatives. However, violence in Afghanistan continues unabated, as the Taliban steps up attacks as part of its “summer offensive.” In fact, the number of civilian casualties have risen high enough to put 2015 on track to become the worst year yet in the conflict torn country.

The above scenario raises two important points: one) given the upswing in violence, talks are more crucial than ever, and two) the ground for peace is more solid under the new government led by President Ashraf Ghani -- who, unlike his predecessor, is open to making concessions that would facilitate talks; this includes the huge concession in the form of improving relations with neighbouring Pakistan.

In regard to the first point, in its annual report released earlier in the year, the UN Mission in Afghanistan has said that the number of civilians killed or wounded in the troubled country climbed by 22 percent in 2014 to reach the highest level since 2009. Figures for 2015 show a similar upward trend. The UN agency documented 10,548 civilian casualties in 2014, the highest number of civilian deaths and injuries recorded in a single year since 2009. They include 3,699 civilian deaths, up 25 per cent from 2013 and 6,849 civilian injuries, up 21 per cent from 2013. Since 2009 -- when UNAMA began tracking casualties -- the armed conflict in Afghanistan has caused 47,745 civilian casualties with 17,774 Afghan civilians killed and 29,971 injured.

The UN says that Taliban militants were responsible for 72 per cent of all civilian casualties, with government forces and foreign troops responsible for 14 percent.

At one point, the peace talks looked set to fail as the Taliban vowed to push through with the “summer offensive” following the White House’s announcement that the United States will maintain its current 9800 troops in Afghanistan through the end of 2015, as opposed to an earlier plan of cutting the number to 5500. The Taliban reacted sharply to the statement with Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid saying, “This damages all the prospects for peace … This means the war will go on until they are defeated.”

Other factors also contributed to making the talks a difficult proposition. For one, the rift between the top two leaders of the militant group. The two in question are political leader Akhtar Mohammad Mansour, who favors negotiation, and battlefield commander Abdul Qayum Zakir, a former Guantanamo Bay detainee, who opposes any dialogue with the Afghan leadership. Sources state that the two met recently to address their personal differences, but no headway could be made on the issue of talks, with Zakir of the view that the Afghan government was illegitimate and that real power remained with the US any way.

The announcement of the change in plans of troop withdrawal tilted the position in favour of Zakir, with the Taliban command being clear from the start that the removal of foreign troops would be one of the prerequisites for the commencement of talks.

The talks, however, seemed to have pulled through, albeit only in the form of a start as of now. Months of informal and formal dialogue in Qatar, China, Norway and Dubai paved the way for the meeting in Oslo and now the Afghan delegation visit to Islamabad.

TOLO spoke to former Taliban commander Syed Akbar Agha about the talks. "If consultations and meetings between the government of Afghanistan and the Taliban are conducted on a regular basis, it would bear positive outcomes on the issues facing Afghanistan," Syed Akbar Agha said.

While the talks finally seeming possible is a major achievement, bottlenecks do remain. This is evinced by the fact that the Taliban recently rejected a call from the Afghan Religious Scholars' Council to put in place a ceasefire during the holy month of Ramadan.

Coming to point number two, i.e., Ghani conceding on Afghanistan’s relationship with Pakistan, it is worth noting that the latter is crucial to the talks owing to its leverage over the Taliban leadership. The two countries recently signed an agreement between Afghan National Directorate of Security (NDS) and Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence (ISI).

Pakistan and Afghanistan have thus far shared a tense history, which the new Afghan President Ashraf Ghani has set to improve, partly because of Pakistan’s influence over the insurgents. This influence, however, has been the main source of ammunition for Ghani’s anti-Pakistan critics, who are accusing the Afghan leader of sleeping with the enemy so to speak.

When Ghani came to power in September last year, he quickly signalled a change in policy. Ghani soon after being sworn-in visited Pakistan, and then Pakistan’s army chief and head of intelligence visited Kabul. Afghanistan and Pakistan’s tense equation had sunk to an all-time low under the presidency of former Afghan President Hamid Karzai. Karzai had been openly critical of Pakistan -- accusing the neighbouring country of supporting the Afghan Taliban and providing refuge to the group’s leadership.

Ghani, unlike his predecessor, reached out to Pakistan. Delegations from the two countries made visits across the border; six Afghan army cadets were sent to Pakistan for training; military efforts were coordinated across the shared border; and Ghani and Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif both issued statements in support of cooperation and bilateral ties.

The shift in policy seemed to be bearing fruit, with reports circulating that the Afghan Taliban -- under pressure from Pakistan was on the verge of agreeing to talks with the Afghan leadership. This was huge. For the first time in thirteen years -- since the US invasion of Afghanistan -- the Taliban, which has thus far maintained that the Afghan government is illegitimate, was ready to initiate a peace process.

Pakistan’s support was the crucial factor in enabling talks. A report in The Express Tribune quoted an unnamed former top commander of the group saying, “Taliban officials, who had been involved in talks with the Pakistanis and the Chinese, and had sought time for consultations with the senior leaders, have received a green signal from the leadership,” adding that “Pakistani officials had advised Taliban leaders to sit face-to-face with the Afghan government and put their demands to find out a political solution to the problem.” The same report quoted another unnamed Taliban source confirming the report and adding that “a small delegation will be visiting Pakistan in days for consultations” to be able to take the discussion with the Afghan government forward.

Then Ghani’s trip to Washington happened, where US President Barack Obama announced the decision to slow troop withdrawal. The Taliban, in turn, issued a statement vowing to continue fighting. "This damages all the prospects for peace, Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said of the announcement. “This means the war will go on until they are defeated.”

In fact, Ghani’s predicament -- of needing the US and wanting to begin a dialogue with the Taliban -- is reflected in a statement made by the Afghan President whilst in Washington. Ghani issued an apology -- of sorts -- to the Taliban. He said that peace with the militants was “essential” and that some Taliban members suffered legitimate grievances. "People were falsely imprisoned, people were tortured. They were tortured in private homes or private prisons," Ghani said (as reported by Reuters). “How do you tell these people that you are sorry?" he added.

All this has been the source of much criticism. In an interview with The Guardian, former Afghan President Hamid Karzai -- said that the country’s historic struggles against British imperialism and Soviet invasion will have been in vain if it succumbs to pressure from Pakistan.

This view was echoed by Karzai’s associates who sat in on the interview. Rangin Dadfar Spanta, a former foreign minister and national security adviser said that the policy amounts to the humiliating “appeasement” of a hostile power who would never change its ways. In a similar vein, Omar Daudzai, one of the most influential officials of the Karzai era who served as chief of staff and interior minister, predicts, “There could be a bloody summer, there will be fighting and there will be disappointments on the dialogue table from time to time.” Daudzai, a former ambassador to Islamabad, added that whilst he thought Ghani’s attempts to woo Pakistan were “courageous,” they would ultimately fail to change the country’s behaviour. “He has taken controversial steps that his predecessor didn’t take, and now we have to wait to see whether the Pakistani side is sincere or not,” he said. “But I am far more sceptical than I ever was before about Pakistan’s sincerity.”

And this is by no means an isolated view. An important figure within Afghanistan, Karzai echoes a distrust that runs deep with the Afghan people. Ghani, therefore, will inevitably -- sooner rather than later -- begin to face pressure in showing that his policy translates into results beneficial to Afghanistan.

Given all of the above, Mullah Omar’s death will have far reaching consequences on the prospect of peace in Afghanistan.