Battle For Ramadi: Advantage Islamic State in Official Play of Identity Politics

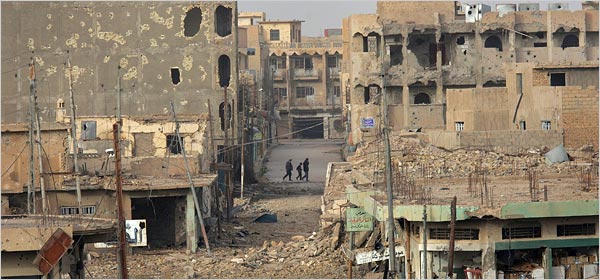

Ramadi

NEW DELHI: When Iraqi forces retook the city of Tikrit in March and Kurdish forces managed to secure Kobani, it seemed like the tide was turning against the Islamic State. This weekend, however, things changed as the militant group took control of the city of Ramadi, the capital of the important Anbar province and home to half a million people.

The loss of the city is a serious setback for more reasons than one. The obvious reason is that it is an important city in a strategically important area. Other reasons include that the fall of Ramadi gave the militants access to a store of weapons, that it serves yet another blow to the Iraqi security forces who are struggling to regain confidence after the fall of Mosul last year, that it highlights the Iraqi Premier Haider al-Abadi’s weakness as the retake of Anbar was supposed to be his big show, and that it proves that the Islamic State is still a force to reckon with. This last point is especially important as Ramadi was witness to a major battle in the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. The US war against terror that followed sought to wipe out Al Qaeda, only instead to replace the group with something far more dangerous and resilient.

At the time of writing, a column of 3000 Shia militia were being moved into Ramadi to try and wrestle the city from the grips of the Islamic State. They are of course backed by the all powerful US-led coalition, that unleashed 19 strikes near Ramadi over the past 72 hours at the request of the Iraqi security forces.

This one fact -- of Shia militia being sent into Sunni territory to battle Sunni militants -- is characteristic of the current crisis in the middle east. The reason why Haider al-Abadi was appointed Prime Minister was because former PM Nouri-al-Maliki was blamed for pursuing divisive policies that have alienated the Sunni minority in Iraq’s north, and in turn, have bolstered support for IS militants amongst an aggrieved population.

Whilst it is true that Maliki and his Shia dominated administration in Baghdad pursued discriminatory policies, the US played an instrumental role in Maliki’s rise to power in the first place, in addition to consistently supporting Iraq’s divisive politics. This includes siding with the Iraqi government’s military crackdown on Anbar last December and the decision to clamp down on protests in Falluja using the rouse of “anti-terrorism.” Falluja was the first city to fall to IS militants at the beginning of last year.

And replacing Maliki has not changed a thing. The context is far more important than band-aid solutions and the context lies in the creation of sectarian identities in Iraq. When the US invasion toppled Saddam Hussein, a need emerged to replace the security vacuum with a new political elite. The main opposition to Hussein at the time were ethno-sectarian parties, and the US brought these factions to power cementing identity politics in the region.

Fanar Haddad, of the Middle East Institute in Singapore, points out that the politicians who came to power post 2003, were not politicians who happened to be Shia, but rather, Shia politicians with a fundamentally Shia-centric ideology and political outlook.

Further, post 2003 institutions came to be organised along sectarian lines. For instance, the Iraq Governance Council, which served as the provisional government of Iraq from July 13, 2003 to June 1, 2004 was formed along ethnic lines -- comprising of 13 Shias, five Sunnis, five Kurds, one Turkmen and one Assyrian.

In today’s Iraq, the Prime Minister is a Shia, the speaker of Parliament a Sunni, and the President a Kurd.

This creation of identity-based politics, paved the way for sectarian identity to become a key political factor. Prior to 2003, although a limited notion of a Shia identity and a Kurdish identity did exist in Iraq, there was no concept of a homogenous Sunni identity. The divisive policies of the Iraqi state -- facilitated by the US -- have paved the way for the emergence of a Sunni identity.

It is this emergence of a Sunni identity rooted in the notion of victimhood, that made the emergence of IS in Iraq possible. The group has existed under various names, first coming into existence in early 2004 as the Jam??at al-Taw??d wa-al-Jih?d, or "The Organization of Monotheism and Jihad" (JTJ). The founding ideology of the group was based on resistance to American intervention in Iraq, with foreign fighters allegedly playing a key role in the establishment of its network. At this point, the group was led by the late Abu Musab al Zarqawi.

The group soon after swore allegiance to Osama Bin Laden, and changed its name to Tan??m Q??idat al-Jih?d f? Bil?d al-R?fidayn, or "The Organization of Jihad's Base in the Country of the Two Rivers.” At this point, the group came to commonly be known as “Al Qaeda In Iraq” although it never formally went by that name.

In 2006, the group merged with a number of other militant groups, to form the "Mujahideen Shura Council," which later that year, following the death of Zarqawi at the hands of US forces, organised itself into the “Islamic State of Iraq” (ISI) or the Dawlat al-?Iraq al-Isl?m?yah. It was in this year that the group made some key advances, securing the Dora neighbourhood in southern Baghdad.

In 2007, it is estimated that the group killed over 2000 civilians, targeting Shias specifically in its onslaught. In June 2006, ISI killed 13 people at a meeting of Al Anbar tribal leaders in Baghdad, saying that the attack was in response to the rape of a Sunni woman by Iraqi police.

In 2009, the group claimed responsibility for the October Baghdad bombings, in which 155 people were killed, and the December Baghdad bombings, wherein 127 people died. The group followed these attacks with a January 2010 bombing that killed 41 people, an April 2010 bombing that killed 42 people, an August 2010 Baghdad bombing, and a December 2010 Church attack. It continued bombings in 2011 and 2012, during which time it began making inroads into Syria. In June 2013, the group attacked prisons at Abu Ghraib and Taji in Iraq, freeing several hundred prisoners.

In Syria the group began consolidating itself the city and province of Raqqa, expanding into northwest areas of the country. In September 2013, the group overran the Syrian town of Azzaz, with the Syrian Observatory of Human Rights labelling the group as the “strongest group in Northern Syria” by November 2013.

As the group expanded from Iraq into Syria -- establishing a stronghold in Ar-Raqqah province -- it renamed itself the "Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant", or the "Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham” in 2013, under the supervision of its current leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who took over in 2011. The name change was based on the Baghdadi’s intent to merge ISI with the Syria-based Nusra Front. Nusra Front and Al Qaeda leaders immediately rejected the merger.

The group has often been referred to as an Al Qaeda off-shoot, but the exact nature of its relations with the Al Qaeda are not clear. In recent months, both groups have made statements disassociating themselves from the other, with ISIL leader Al-Adnani saying, ““the ISIL is not and has never been an offshoot of Al Qaeda.”

When the group captured Mosul in June this year, the international community was taken by surprise at the strength of a relatively unknown Iraqi group. IS’ gains in Iraq are directly linked to its operations in Syria, where it had come to control large swathes of territory in its fight, along with other groups, against Syrian President Bashar-al-Assad.

The advance of anti-government forces in Syria, was made possible in turn, by the United States and allies assistance to Sunni rebels, who share with the US the objective to topple Alawite leader Assad. The US greenlighted Turkish and Saudi aid to anti-Assad rebels, supplied these groups with material and financial assistance, and used the CIA to train rebels at a secret base in Jordan.

This not to suggest that the rebels in Syria present a homogenous group, as there is considerable infighting, with the IS militants facing setbacks at the hands of the Islamic Front and the Free Syrian Army, for instance. However, affiliations change rapidly, and the IS group -- when it was known as Al Qaeda in Iraq -- had expressed solidarity with the rebels in Syria, following which the US immediately increased aid to anti-Assad forces. The aid began as non-lethal aid, but following a June 2013 White House statement that said there was reason to believe that Assad had been using chemical weapons against rebels, the US decided to extend lethal aid to anti-Assad militias. The total aid given by the US to rebels in Syria, according to USAID figures, amounts to over $1 billion.

For FY2015, the US Congress is reportedly seeking $2.75 billion in funds to finance its role in the Syrian crisis, of which $1.1 billion is marked for humanitarian aid, $1 billion for regional stabilisation and $500 million for DOD-led arming and training of opposition forces.

The United States’ dual policy -- of complicit support and aggressive resistance, simultaneously -- has shaped the new Middle East, which in turn, is characterised by the factors that are invoked to explain IS’ rise: growing sectarianism, the absence of an Arab governance model, and an emerging security vacuum in the region.