The Ordinance Criminalising Triple Talaq is Overtly Political and Bad in Law

The Ordinance Criminalising Triple Talaq is Overtly Political and Bad in Law

For some time now the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which is generally viewed with scepticism by Muslims because of its stridently anti-Muslim politics, has begun projecting itself as a saviour of Muslim women, and has systematically been raising the issue of “gender justice and gender equity” among Muslims.

On September 19 the Union Cabinet approved an ordinance criminalising the practice of triple talaq (divorce) or talaaq-e-biddat, which was promulgated that very evening after receiving the assent of President Ram Nath Kovind. The provisions of the ordinance are almost identical to those in the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Bill, 2017, which was passed by the Lok Sabha last December but remains stuck in the Rajya Sabha.

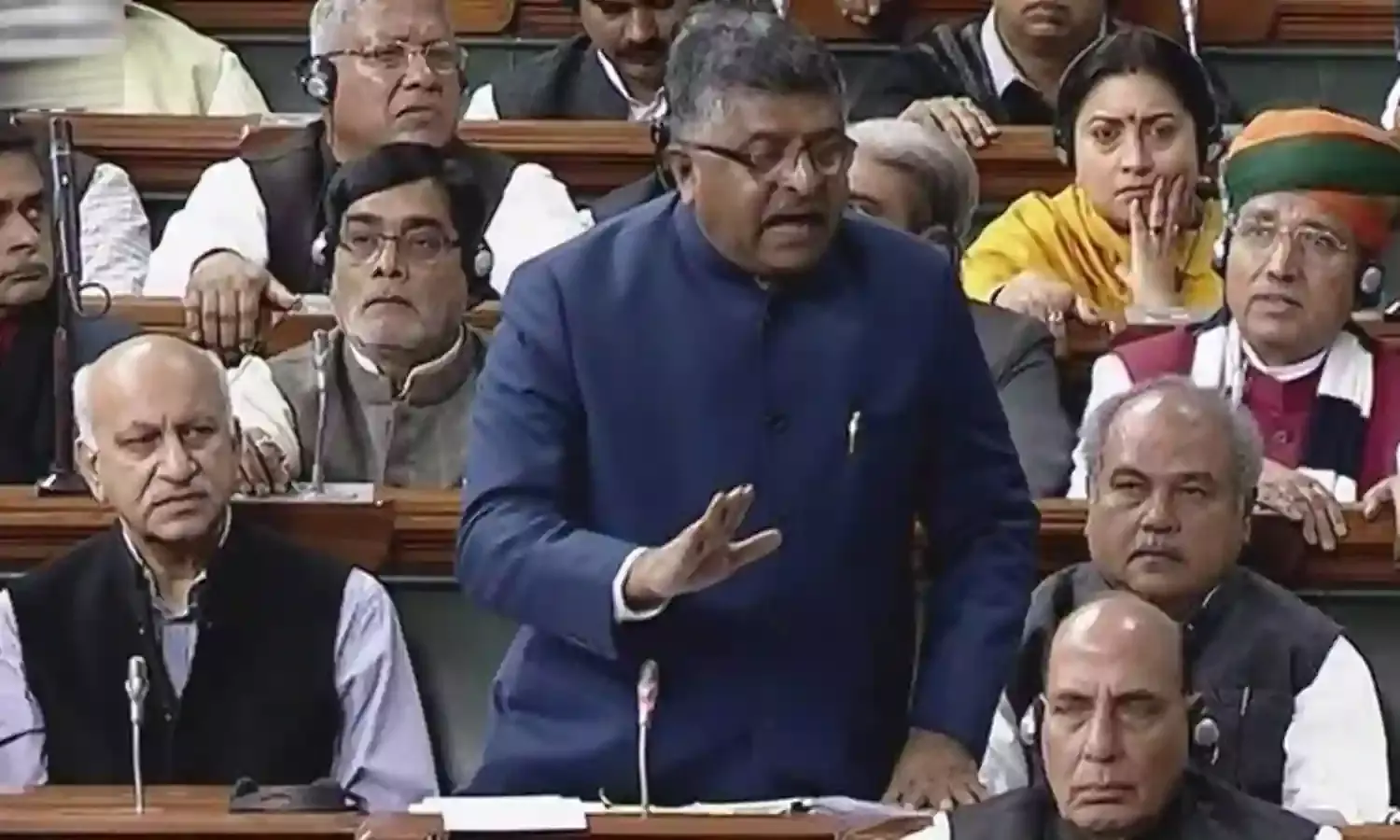

Union Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad unceasingly defended the ordinance, stating that there was a "compelling necessity and overpowering urgency" for it, as the abhorrent practice of triple talaq continued unabated despite being outlawed by the Supreme Court last year. He stated that 430 cases of triple talaq had been reported between January 2017 and September 13 of this year, of which 201 date from after the Supreme Court’s judgment invalidating triple talaq.

The timing and the manner in which the ordinance was brought out raises many questions. Contrary to the BJP’s claim, the move seems driven more by political expediency than a want of genuine reform in Muslim personal law.

Given that the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Bill 2017 is already pending in the Rajya Sabha, the government could have built a consensus by addressing the objections raised by the opposition parties, who are in a position to block the legislation. Instead the BJP preferred the ordinance route, despite knowing that it will have a shorter life.

As per the Supreme Court ruling in 2017, in Krishna Kumar Singh vs. State of Bihar, the government will have to bring the ordinance back before the Parliament when it meets for the winter session in November or December, as the repeated promulgation of an ordinance has been declared by the court to be ‘a fraud on the Constitution and a subversion of democratic legislative processes’. The apex court has made the placing of every ordinance before the legislature a mandatory Constitutional obligation, reasoning that it is for the legislature to determine the need, validity and appropriateness of promulgating an ordinance.

The main reason behind the BJP’s hasty decision to criminalise triple talaq seems to be its desire to blame opposition parties for the collapse of the ordinance, as is evident from the law minister’s statement. He squarely blamed the Congress for stalling the bill in the Rajya Sabha, and preventing the end of the suppression of Muslim women, for vote bank considerations, despite the fact that "a distinguished woman" was until recently at the helm of the Congress.

Prasad’s statement is a clear indication that the BJP is going to make triple talaq a major poll plank in the forthcoming elections in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Prime Minister Narendra Modi had very aggressively raised the issue of triple talaq in the run up to the Uttar Pradesh assembly elections last year.

On one hand, the BJP will try to woo Muslim women by masquerading as a champion of their cause, while projecting the Congress as a major stumbling block in their empowerment. It will also seek to further consolidate its traditional Hindu voters, by sending the message that the BJP is the only party which does not appease Muslims and has the courage to reform Muslim personal law, which no other party could dare to do for fear of losing “the Muslim vote”.

Besides being overtly political, the move is fraught with numerous inherent problems. For one, the ordinance was not needed at all after the Supreme Court had declared triple talaq as void and illegal. After this judgment, to criminalise triple talaq is a meaningless exercise, and of no consequence in the eyes of the law. There is a tangible logic in the ordinance of penalising a man for an act which is inconsequential in law.

Moreover, there are already adequate provisions in both criminal and civil law to which Muslim women can take recourse to protect their rights, such as Section 498 of the Indian Penal Code, dealing with cruelty to wives, and the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, which secures the rights of all women facing domestic violence to maintenance, residence, protection from violence and to custody of their children. The ordinance adds nothing new to these protections.

The penalty imposed for triple talaq is excessively disproportionate, and violates one of the fundamental principles of criminal law, that the severity of punishment must be commensurate with the seriousness of the crime. This principle of commensurate deserts permits severe punishments only for serious crimes. Under criminal law jurisprudence, imprisonment is necessarily treated as a severe penalty and must be limited to serious offences which cause or risk grievous harm.

The Indian Penal Code provides for only two years’ imprisonment for serious and heinous crimes such as rioting with a deadly weapon which is likely to cause death (Section 148), or promoting enmity between classes of people (Section 153-A). In the light of our sentencing pattern, there seems to be no logic to awarding three years’ imprisonment for the breach of a civil contract, which is what a Muslim marriage is.

The ordinance also provides for a subsistence allowance to be paid to the wife and her children, as determined by a judicial magistrate. But there seems to be no answer as to how the husband would pay this subsistence allowance while in jail, given that the practice of triple talaq is more common in the poorest strata of Muslim society.

Although the ordinance incorporates certain changes to the original bill to allay fears about its possible misuse, it still suffers from legal and technical infirmity which needs to be rectified.

For instance, it introduces the provision of bail – but the offence remains cognisable and compoundable, which means that the husband can be arrested without a warrant. Only a magistrate is empowered to release the accused on bail, and only after hearing the wife. The scope of complainants has also been reduced to the wife or blood relations.

The ordinance talks about the possibility of reconciliation and compromise by the parties, but critics rightly fear that a criminal case against the husband would jeopardise any such prospect.

The provisions of the ordinance are contrary to the stated goal of helping Muslim women and providing them greater security in matrimonial relations. Conversely, it appears that criminalising the already invalid practice of triple talaq in this manner would end up harming them.

The practice of triple talaq is a social evil and it will not end merely by being criminalised by executive order. It is also erroneous to believe that Muslim men will no longer resort to it, as there is no credible empirical evidence to suggest that the rate of crime is reduced substantially with harsher punishment. The move may certainly be politically beneficial to the BJP but it is unlikely to be any help to vulnerable Muslim women, as the government insists.

(Aftab Alam is professor of political science at the Aligarh Muslim University).