Accessing Contraceptives Under the Shadow Ban in Tamil Nadu

Moralising can be hazardous to health

CHENNAI: It was a frantic woman in her twenties on the other side of the phone. She needed help getting a morning after pill, in a city where they are rarely available.

Such calls weren’t new for Apoorva Mohan, a women’s rights activist based in Chennai.

She recalls how Adya (name changed) could not visit a gynaecologist in Erode where her family lives, for fear she would be judged. Adya travelled in haste to Chennai, where Mohan suggested some pharmacies she might be able to procure emergency contraceptive pills. But none of the pharmacies she checked had them.

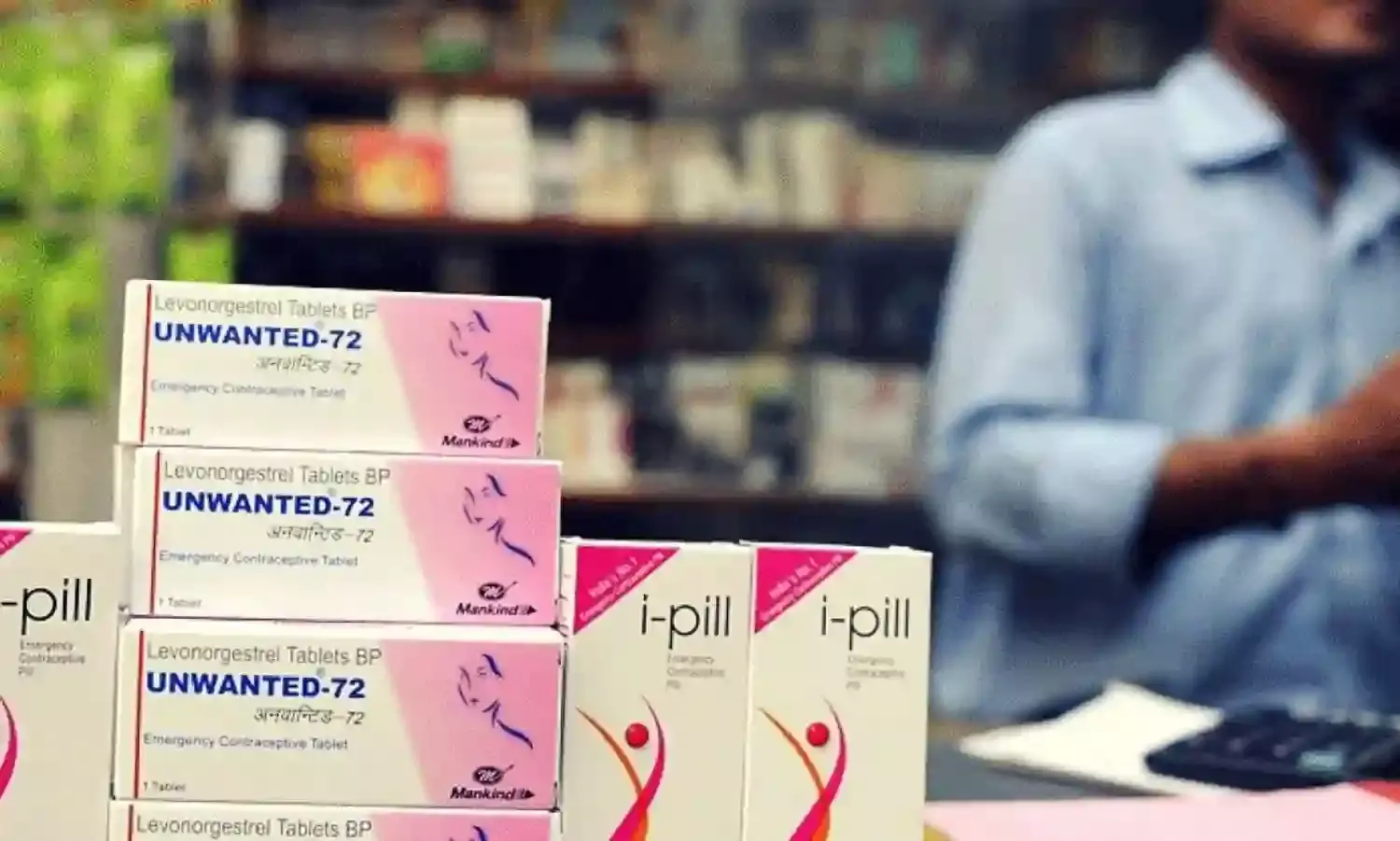

Many here falsely believe that there is a ban on stocking i-pills or other emergency contraceptives. There is no official ban, yet Tamil Nadu has completely cut off women’s access to over the counter ECPs over the years, under a shadowban operating on moralistic grounds.

These pills, which are easily available elsewhere in the country, need to be taken within 72 hours of unprotected sex to reduce the chance of pregnancy.

Denial of access to emergency contraceptives leads to increased risk of unsafe abortions and unwanted pregnancies. Those who can are also known to procure the pills from outside the state.

“I was looking for i-pills for my girlfriend, and I went to five to six pharmacies looking for them, but I couldn’t find one single pill at any of those. Luckily one of my friends was travelling from Hyderabad, and I asked her to get it for us,” says 28-year-old Sankesh Mehta.

In November 2008, the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare issued guidelines saying that ECPs could only be provided by healthcare workers: pharmacists, nurses, family welfare assistants, community-based health workers, doctors, midwives or paramedics.

Nevertheless, due to internal restrictions from state officials, pharmacies in Tamil Nadu gradually stopped stocking morning-after pills, until in 2016 they had disappeared completely from store shelves.

The denial of access to i-pills became a topic of debate after officials were quoted as saying that youngsters were “misusing” them.

“Lots of students were misusing it, students who were as young as teenagers. Therefore they banned the sale of i-pills,” says Muruga, a pharmacist in Velachery.

Archanaa Seker, a social rights activist, recalls that while the Madras High Court did raise questions on the sale of i-pills, and there were debates on the issue, no official ban was imposed.

Seker has been campaigning against the shadowban, seeking clarification from officials. “There has never been a ban in reality, yet they are purposely made unavailable in Tamil Nadu,” she says.

The pills are almost impossible for people to access or buy. They should technically be sold and made available to all, says Seker, but in effect drug stores or hospitals cannot keep them in stock.

Notions of morality play a big role in this denial.

“It continuously surprises me how people trained in science have such unsubstantiated morale. It is important to understand that young people are curious about each other’s bodies, and often tend to engage in sexual activities. Sex education regarding safe sex and busting myths about condoms and pills must be mandatory,” she said.

In November last year Manohar, the president of the Tamil Nadu Chemists and Druggists Association, told the media that sales of emergency contraceptives remained restricted because overdosing on them causes prolonged health issues in women.

But people also overdose on paracetamol, which can cause liver failure, Seker points out, “Yet they are not banned. ECPs are for women, and people tend to tie moralistic values because it is concerned with a woman’s vagina, and we like to control women’s body parts.”

Like Seker, other activists like Apoorva Mohan have been privately providing these pills in Chennai for years. They get the word out on their social media handles, and receive a barrage of requests from women throughout the state looking to avoid an abortion.

“When people contact us for these pills from different cities in the state, we send out several parcels of these pills to Pondicherry and Coimbatore with the help of our friends who are visiting the cities,” Mohan explains.

She says she used to get many requests, from women and men, to help them find a gynaecologist they could reach out to for an abortion. This was primarily because people had been denied access to ECPs.

“Speaking from the kind of messages and requests that I receive, abortions have become more common from the past couple of years. This is bad because it’s a painful process and costs a lot,” said Mohan.

It has become a challenge for these activists to help people obtain ECPs under the shadow of an unspoken ban, or even to help them get safe abortions, as misconceptions are allowed to flourish by the moralists.

Mohan related her experience on Twitter of reaching out to gynaecologists in the city who were willing to perform abortions.

“People tagged the Chennai police Twitter handle to my tweet and said that I was running an illegal abortions racket. This is why we take major precautions to protect ourselves and the people who reach out to us.”

Gynaecologist Tarun Joseph, who has a clinic in Chetpet, says abortions must not be taken lightly, and contraceptives are a godsend to prevent situations like these.

“Earlier in my career I had witnessed a girl getting an abortion done without telling her parents. She would constantly pass out due to excessive bleeding. Sometimes doctors use invasive technology with foreign bodies entering the vagina that could harm her to the point of never being able to give birth.”

Joseph explained that prohibiting access to emergency contraceptives forces doctors to prescribe their patients a higher dose of normal contraceptives, whose effect may be the same as i-pills, but whose side effects are often worse.

“A normal contraceptive pill contains two hormones, estrogen and progesterone. An ECP however contains only progesterone. The addition of estrogen to a contraceptive can have a horrendous side effect. Therefore, we prefer to prescribe an emergency pill over a normal one,” he said.

After unprotected sex, most people do not think of going to the gynaecologist right away. With essential contraceptives withheld from stores and hospitals, one needs a prescription to order them and the process takes much longer. It may ultimately be of no use if one crosses the 72-hour mark.

Many pharmacists do not understand the difference between contraceptive pills and abortion pills, says Seker. “Many believe they are the same, which is an additional cause of pharmacies not stocking these pills.”

A survey last year by the Foundation for Reproductive Health Services India in collaboration with Marie Stopes International reportedly found that only 3% of Tamil Nadu pharmacies stock ECPs, and only 2% stock medical abortion pills. 90% of those who do not stock emergency contraceptives believe it’s officially banned, according to the report.

The state government’s Directorate of Drugs Control has been planning to make the pills available since November 2020. Interventions by Seker, Mohan and other activists reportedly prompted it to clarify to its Drug Inspectors statewide that there is no ban on emergency contraception.

However, the shadow ban has not been entirely lifted. Several pharmacists remain unaware of the clarification that was issued last year.

A pharmacist from Sri Kumaran Medicals assured us that he doesn’t stock up on the pills. “We are not allowed to keep them. It is banned.”

Ravi Shankar, another pharmacist, explained that “a lot of times, we have inspections taking place to check if we are selling anything illegally. The inspectors check if we have these pills, and in case we do, our license is also capable of being cancelled. That fear alone keeps us from storing the pills.”

The shadowban has its loopholes, however.

“We sell No Will instead of i-pills,” said Muruga, the pharmacist in Velachery.

“The government officials strictly prohibit the latter. We only sell the pill to those who we think legitimately need it, we don’t sell it to students. This is why we often check for a doctor’s prescription,” he said.

“The components for both the pills are the same. However, there is no clear reason for the ban. The only striking factor here was the popularity of the latter among youngsters that was a matter of concern among the official bodies,” said Muruga.

Besides NoWill, which is also a hormonal contraceptive, there are several other replacements for the i-pill in the Tamil Nadu market.

The manager at Om Medicals in Velachery said i-pills were only permitted to be sold by hospital pharmacies. But a Neo Life Hospital pharmacy we checked with did not stock them.

“We never have any contraceptive pills in stock. We cannot even procure them on order or prescription,” said the woman in charge, requesting anonymity.

Most pharmacists say they can only order ECPs if someone comes to them with a doctor’s prescription. Sometimes, the doctors themselves give them the pills.

Dr Joseph does not keep the pills with him, and says very few doctors do.

“It’s a struggle when patients come with the hopes to take ECPs because mostly no one has them. Hardly three pharmacies I know keep these pills with them. Otherwise, I’m forced to prescribe medicines with a higher dose.”

Low awareness about ECPs and the state’s contraceptive policies have effectively shrouded many pharmacists’ beliefs.

Years of an unspoken ban and government inspections have created this situation across the state, increasing the risk to women’s health and people’s well being.

From all accounts, government officials have done little to improve the situation.