India Kills Her Daughters With Impunity

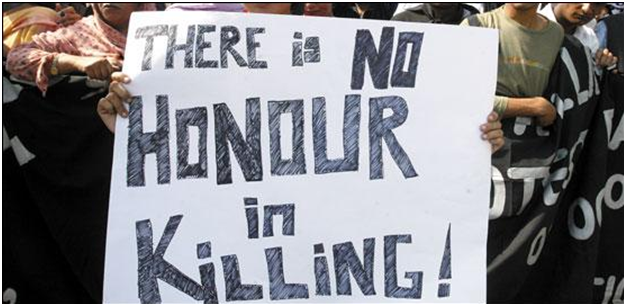

Placard carried by protesters in India

DOHA(IPS): According to statistics from the United Nations, one in five cases a year of honour killings internationally comes from India. Of the 5000 cases reported internationally, 1000 are from India. Non-governmental organisations put the number at four times this figure. They claim it is around 20,000 cases globally every year.

While traditionally occurring in villages and smaller towns in India, honour killings have been on the rise and are reported sporadically in the media. The double murder of a 14-year-old school girl and a 50-year-old domestic in a New Delhi suburb with its honour killing subtext has received unprecedented attention, and is perhaps urban India’s most hyped alleged honour killing.

Although the Talwars, the parents of the girl, were charged with the murders of their daughter Aarushi and their domestic help Hemraj, the ‘motive’ for the murders was attributed to honour killing. Special Central Bureau Judge Shyam Lal, while convicting the parents earlier this week, said the dentist couple had found their daughter and the help in an “objectionable position”.

The judgement, based on circumstantial evidence, has however left many unconvinced. But irrespective of what the truth is, the Aarushi case has shone the spotlight on honour killings.

“The social moorings of this case and its ramifications on India’s middle class could not have been lost on anyone,” observed Anubha Bhonsle, an anchor for CNN-IBN, in one of her programmes.

However, if the judiciary, through this verdict, is trying to drive home the message that there will be zero tolerance for honour killings regardless of how powerful the perpetrators are, the question that will come up is whether the courts will apply the same rigour in some of the most gruesome cases of honour killings taking place in rural India, far from the gaze of television cameras.

Some grisly cases that have been reported in the media in recent times from different regions in the country include that of 23-year-old Dharmender Barak and 18-year-old Nidhi Barak, who paid a heavy price for defying their families and falling in love.

The couple, from a village in Rohtak district in the northern state of Haryana, were tortured, mutilated and killed in public view by the girl’s father and their relatives when they tried to elope. A friend the couple had confided in leaked their plans to the girl’s parents, who lured them back with assurances, only to allegedly kill them in the cruelest manner. The police are treating the double murder as an honour crime.

In September 2013, the Haryana police arrested a police sub-inspector in connection with the killing of a 19-year-old girl from Panipat. Meenakshi had eloped with her boyfriend and the cop had tracked her down and handed her over to her family, who then allegedly murdered her.

On Oct. 24, 2013, in another case from Haryana, a 15-year-old Muslim girl from Muzaffarnagar was banished to her uncle’s house to prevent her from seeing the boy she was in love with. Her uncle allegedly murdered her and buried her in Panchkula District.

While cases of honour killings continue to pile up, convictions are few and far between.

In July 2013, Arun Bandu Irkal from Yerwada in the western state of Maharashtra was served with a life sentence. In 2002, the accused had reportedly stabbed his 17-year-old daughter Yashodha 48 times with a pair of scissors for having an affair with a boy from another caste. She did not survive the attack.

The accused surrendered, then skipped bail and was finally re-arrested in 2011. The court convicted him this year for murdering his daughter. The court said “honour” was the motive behind the murder.

On Nov. 1, 2013, in Bhopal in the central state of Madhya Pradesh, a lower court announced a life term for 10 men in a case of honour killing. The men were accused of killing Amar Singh, the elder brother of Sawar Singh, who had allegedly eloped with Hema, the wife of Balbir Singh, one of the accused men.

The men went to Amar Singh’s house, questioned him about the couple’s whereabouts and then poured kerosene on him and set him on fire. He died of the burns.

All these cases have led to a new discourse on legislation. Does India acutely need separate legislation on honour killings? A proposal to that effect has been made by a study carried out for the U.N. Population Fund (UNFPA) on gender laws.

Voices have also been raised to rein in the ‘khap panchayats’ or self-elected village councils made up of male village elders who perpetuate values that, in turn, covertly endorse these killings in the name of saving “the family’s honour”.

Like the Taliban in Pakistan and Afghanistan, the khaps have attained notoriety by issuing diktats on dress code for women and demanding a ban on the use of cell phones by young girls and women.

In both rural and middle-class urban India, the onus for upholding family morality falls on the women in the family – the daughter, daughter-in-law, wife and mother. By daring to choose a life partner other than the one selected for her by her family, or by committing adultery, she violates the family’s honour. Both she and her lover can face death as a consequence.

Recently, a group of khap panchayats filed a document before the country’s highest court saying they had been wrongly charged for encouraging honour killings in rural India. Earlier, a women’s rights group, Shakti Vahini, had petitioned the Supreme Court to instruct the government to be more proactive when honour killings are carried out.

They blamed the khap panchayats for endorsing patriarchy, which they said reinforced the subjugation of women in society and the resultant honour killings.

The court summoned 67 representatives of the khap panchayats to explain their role in honour killings. The representatives submitted a written reply, saying the responsibility for such killings did not lie with them but with the families who failed to prevent their daughters and sisters and wives from interacting with men, which resulted in shame and ostracism by the community.

They argued that women who feared their male relatives never committed such acts and therefore never had to face such consequences. In short, the khap panchayat representatives overtly defended honour killings.

But the problem of honour killings goes well beyond the shores of rural and urban India. They are common in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and Bangladesh also has honour killings or assaults in the form of ‘acid attacks’.

Acid attacks, torture, abductions and mutilations all come under this category of crime.

The problem is that in most countries, there is confusion about the definition of what constitutes an honour killing. This confusion often results in the victim failing to get justice. Many families report these killings as suicides and escape punishment under the law, according to international human rights and women’s groups.

According to U.N. statistics, the United Kingdom has 12 cases of honour killings every year, the majority of them among the Asian diaspora. Will countries abroad also have to legislate on honour killings if South Asian and West Asian men carry their patriarchy to foreign shores and murder women who break so-called “cultural norms”?

This year’s Emmy award for best documentary went to a film on honour killings in the UK. Banaz: A Love Story, directed by Deeyah Khan, is about the honour killing in south London of 20-year-old Banaz Mahmod who was murdered by her family in 2006.

Mahmod’s Iraqi Kurd father and relatives felt she had brought shame to her family and community by leaving her husband, who was abusive and an alleged rapist. Mahmod had fallen in love with another man and ended up paying with her life. She was raped, strangled to death and her body was put in a suitcase.

Her father and uncle now face life sentences in UK jails. Two other men, who had to be extradited from Iraq by Scotland Yard, are also serving prison terms, for 20 years. By making these arrests and convictions test cases, the judiciary and law enforcement authorities hope they can deter families from such criminal acts against their female family members.

A case was recently reported where, after a long battle with the Australian immigration and refugee authorities, a couple, a Sikh and a backward caste Hindu who had married secretly in India in 2007, were granted asylum in the country. The couple had said their lives would be in danger if they had to return to India as they feared honour killing for having defied the caste system.

Even as the dust settles on the verdict for the Talwars in Delhi, it will be a while before Indian society really begins to digest the cancer of patriarchy manifested through honour killings. Like all social evils, unless society shuns these practices, the police and judiciary alone cannot save women who want to break free from arranged and abusive marriages.

(INTER PRESS SERVICE)