In Search Of The Last Handwritten Deed Writer In Delhi’s Walled City

Eighty-year-old Satya Narayan Saxena sits in his small shop nestled in Old Delhi’s Chawri Bazar

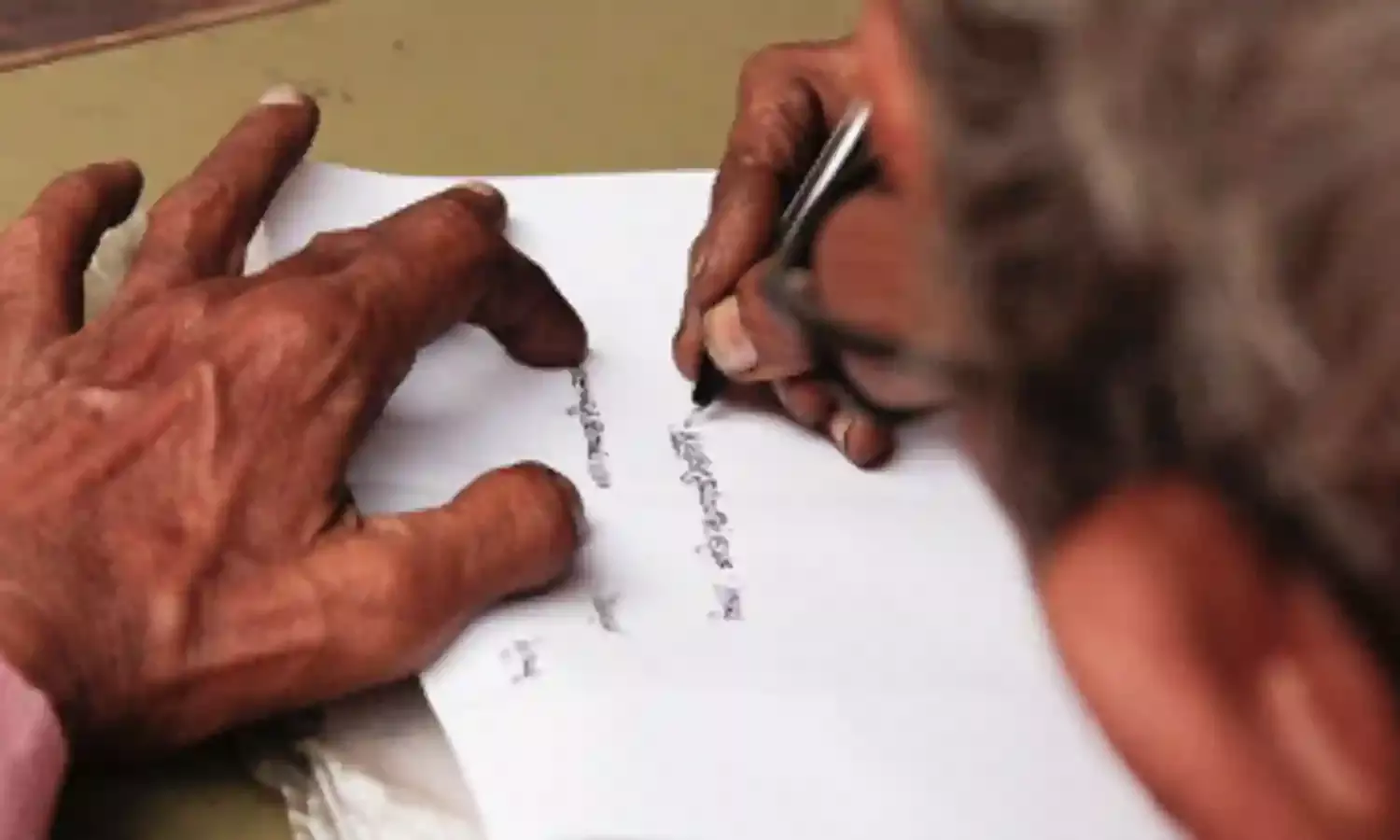

NEW DELHI: His wrinkled hands shiver as he sifts through a dust-laced bag. He fishes out photographs with tourists, old currency bills and lastly his prized possession- pale white deed documents. Eighty-year-old Satya Narayan Saxena sits in his small shop nestled in Old Delhi’s Chawri Bazar. A search for deed writers in Delhi will bring you to his shop, probably the last in the city. Among seven of his siblings, Satya Narayan Saxena was the only one to pick up this art from his father at the age of 15 in 1962.

Nowadays, hand-written deeds in Hindi and Urdu have been replaced by type-written documents. Like many other professions, digitisation has brought an end to the trend of deed writing, says Saxena. “Earlier, my shop was abuzz with customers wanting their documents written in Hindi and Urdu. But now my work is reduced to the mere translation of documents.”

In this shop, Saxena spends most of his time. It was rented to Saxena’s great-grandfather when he shifted to the erstwhile Shahjanabad as a deed writer. Since then, Saxena’s family has been carrying out their occupation from this place. In the next street, his son too owns a shop. Unlike his father, he deals in hardware. Saxena did not ever wish for his children to carry on the family legacy of deed writing. “This profession no more fetches enough money to sustain a family in a city like Delhi,” says Saxena.

From home to shop and back, he always carries a black bag that is stuffed with documents- his mobile museum of memories. Saxena keeps some documents at his workstation, but the older ones are safely piled in his home. There were days when he stayed up till late in the night to write documents. “I have written so many documents that I don’t have to look at a template. I can prepare a document from memory.”

His home, a few blocks away, houses his old deed-documents. Crammed in Old Delhi’s maze of lanes, his three storied house is his abode, a place he hasn’t left in the last 65 years. Here, Saxena finds the serenity to jot down details on pieces of paper.

Over the years, he has written thousands of documents, many of which are withering with time. He ruefully recalls how documents of great historical value were once destroyed by termite.

Even his family is aware of the fact that these pieces of paper mean a lot to him. Yet, the lack of space compels them to make hard decisions. “Once my mother had to burn stacks of these papers without his knowledge. It had enraged him and he refused to speak to us for days. We felt guilty about it, but it was becoming difficult to store so many papers,” his youngest daughter said.

He has also trained many novices who expressed their desire to learn about the art. But once they picked up the tricks of the trade, they left within months. “All of them opened their own shops and churned out documents on their new typewriters.”

Saxena is quite vocal about his contempt for the present times. “People have approached me asking to make false documents. But I have turned them away each time.”

From the days of British rule to present times, he has myriad tales to narrate. Years of dealing with the public in the busy street of Old Delhi has made him a connoisseur of experiences, documents and stories. What is perhaps hard to miss is his fondness for the colonial times. “In those days, even a petty thief could not escape. The British would call the Scotland Yard to investigate than have a thief on the loose!

When motorcars began replacing the tangas, the streets of Chawri Bazaar became a den of chaos, says Saxena.

As he reminisces about old times, he pauses for a moment and surfs through the shelves of his cupboard. Seconds later, he pulls out a small pouch containing sweetened beetle leaves. He tells us that not a day goes by without him enjoying his favourite sweet snack. He carefully places the pouch back inside and continues.

For the last six decades, Saxena has been opening his shop daily without fail. Every day at 11 in the morning, he readies his shop and waits for customers. Every day except on Sundays. “That’s the only day when I spend time with my family. Sundays are for rest,” he declares.

Customers are few and the income is meager but he is not planning onclosing the shop anytime soon. He indignantly asks, “When machines will begin taking over the work of humans, where will people like us go?” He reveals that he used to sustain his family with an income of Rs. 15. Today, writing deeds is not a profitable profession. But having spent a lifetime working in his shop, he is determined to carry on.

Ask him about what he enjoys doing besides work and the reply is almost instantaneous- Reading. A voracious reader, he claims that he once finished reading all the books in the Hindi section of the Delhi Public Library.

Saxena also loves watching Hindi cinema. He candidly confesses that he is a big fan of Meena Kumari and Dilip Kumar.

As his evening tea arrives, he shares another interesting trivia. Over the years, his shop has become a tourist spot for many foreigners visiting Old Delhi. He quickly takes out a stack of photographs where he is seen striking a pose and smiling with the tourists. Many tourists hand-delivered these photographs while some asked their embassies to send it to him. These photographs have now become a treasured part of his professional memorabilia.

One wall of the shop is lined with photographs of his family and two group photographs of the Wasiqanaweesan Association of Delhi. The last meeting was held in 1964. Since then the deed writers never met under any union banner. “We haven’t heard from each other since then. I guess some of them are even no more,” he says while talking about the photographs.

After sunset, the market is brimming with life, yet Saxena decides to call it a day. He packs his lunch box and his bag of precious documents, places it on the side of the footpath as he lowers the shutter. He tries to bargain with the rickshaw pullers to give him a ride home. Not happy with the rates, he walks his way back home.