Millennials, Morality And Indian Politics

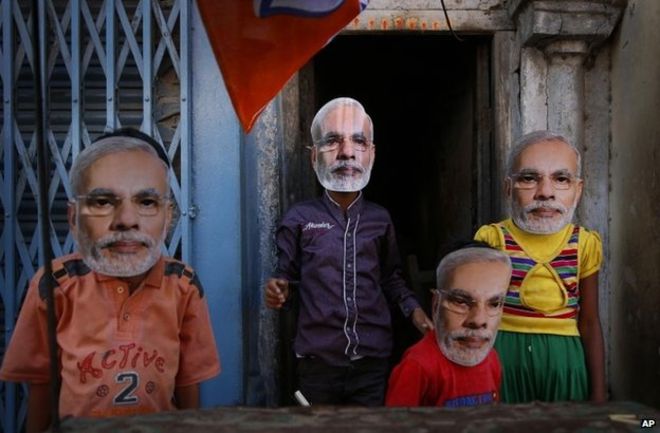

2014 was a definitive year. For millions of millennials in India, it was the first election that really mattered. As was evinced by my Facebook newsfeed, people who hitherto had zero interest in politics were transformed -- overnight -- into overzealous election pundits.

The narrative that emerged in the months leading up to the 2014 general elections was fairly homogenous: Narendra Modi was touted a hero; the Congress -- perhaps deservedly -- was ubiquitously denigrated. I remember a conversation at the time with a vocal ‘Team Modi’ supporter. “I’m sick of the corruption. Sick of not moving anywhere. Sick of the status quo,” a twenty something Delhi-based architect told me. As part of a generation that is constantly seeking change, I understood what he meant. As a Delhi-ite who had witnessed the Commonwealth Games and the scam that had surrounded the event, I even agreed.

I was sick of it all, too. Where I disagreed with the majority was in the support for Narendra Modi. I couldn’t bring myself to endorse a man and political party that had had a role to play in 2002 -- even if that role was limited to not doing enough to stop the carnage. I did not want to give legitimacy to a brand of politics that based itself on othering… on prejudice, hatred and violence. When I put forth this argument, most people quickly pointed to the Congress’ similar brand of politics -- and they were right, the Congress has its own murky, evil past. But I had not been born in 1984. If I were alive, I would have taken a similar position.

That didn’t really work as a counter argument. The sad reality, I realised, was that as far as my self absorbed generation went -- a minority in Gujarat did not matter. It did not fit into their scheme of things. Their idea of India. Their optimism for the future. Over 2000 Muslims losing their lives in a state in one corner of India meant nothing to most of the people I knew. For the majority, the idea of an India that fit in with the ‘India Shining’ rhetoric that was targeted at them, took precedence. Lives lost to get there? What lives, and who cares?

When I argued that legitimising the Gujarat brand of politics will lead to more Gujarats in the future -- people rolled their eyes. While they maintained that they didn’t think that was the case, the truth was, they didn’t really care. As long as it brought with it all those other things -- you know, bullet trains, a seat at the United Nations, more FDI…

This realisation is key, and I’ll come to why a little later.

Cue 2016. It has been about two years of the Modi government, and there has been -- the way I see it -- a decisive shift. Take that architect I mentioned earlier. I met him a couple of weeks ago at a friend’s 28th birthday party. “You know. I hate to admit it but you were right,” he said. I didn’t even need him to elaborate because this admission is something I have heard a countless times in the last six months.

Facebook acquaintances who inundated my newsfeed with pro-Modi sloganeering in 2014 were now leading the opposing tirade. A twenty something entrepreneur, whom I had unwittingly gotten into heated arguments with at the time for his fairly ignorant but frequent Modi paeans, was now routinely posting statuses criticising the very government he had once so fervently supported. A friend’s brother, who didn’t hide his distaste for my views of the then Chief Minister, took out the time to write a long apology, highlighting the reasons why he was wrong and apologising for some of the very rude things he had said to me back then. An industrialist acquaintance, who had thought that Modi was the answer to India’s economic sluggishness, told me he was “disappointed.”

I could go on, but the point that I’m trying to make is that -- at least among my immediate social circle (as determined by Facebook) -- the Modi wave is on the wane, and has been so for a few months.

A few days ago, whilst sipping on masala tea with a likeminded friend, I pointed to the above observation. She immediately agreed. “Think about it,” she said, “I know so many people who went from being pro Modi in 2014 to being openly critical of him in 2016, but how many people do you know who did the reverse? How many people do you know who went from being critical of Modi in 2014, to openly supporting him today?”

The answer? None. (Side note: How many do you know? Comment below).

Getting to the point now -- I started thinking about why that was. Why had the legions of Modi fans that once dominated my Facebook newsfeed moved away?

At first, I thought the answer lay in a moral compass of sorts. After all, millennials are supposed to be more tolerant and more open minded than preceding generations. Maybe all the beef attacks and violence got to them, I first thought. Having not slept for nights after hearing about the lynching of Mohammad Akhlaq in Dadri, or the attack on Dalits in Una, or the recent rapes of two women for ‘eating beef’ in Mewat … (the list goes on) ... it made sense that people would finally reject the associated brand of politics. And if not that, maybe all the communal violence -- the Muzaffarnagars, the Trilokpuris, the Mewats, the Narsingbaris… (this list, again, goes on) -- was the reason. After all, those people that had scoffed when I said -- ahead of the 2014 elections -- that legitimising the Gujarat brand of politics would see more Gujarats, albeit in a different form (meaning 50 people killed instead of 2000), would now agree that I was right. 2015, for the record, saw a 17 percent jump in reported incidents of communal violence.

I almost felt vindicated, and even pleased in the assurance that my generation -- the future of India -- had a moral leg to stand on. That we wouldn’t stand for this hatred, for this vicious brand of political violence. But I was wrong. The reason why my generation has moved away from singing the Prime Minister’s praises has nothing to do with taking a moral position.

Most people in my midst -- I soon discovered -- knew nothing about Dadri, Una, Mewat, Muzaffarnagar, Trilokpuri (the list goes on). They have no idea that two women were recently raped in Haryana by self professed gou rakshaks as “punishment” for “eating beef.” They have no clue that Mohammad Akhlaq’s family, instead of being offered protection by the State after Akhlaq was lynched to death by a mob on suspicion of eating beef, are now being prosecuted -- legally and socially -- for consuming the banned meat. They don’t know where Muzaffarnagar is or why it is significant.

So why then did the majority of my annoyingly vocal Facebook friends move away from supporting Narendra Modi? If it wasn’t the moral argument, what was it?

Hoping to get to the bottom of it, I met a long forgotten acquaintance yesterday for lunch. Yash is a twenty something son of a business family. He’s garrulous and enjoyable in small doses, and a fairly good representative of the target group that I was trying to understand. As subtly as I could, I brought up the current state of affairs in the country. “What do you think of the current political scenario?” I asked, trying to be nonchalant but failing. Yash didn’t seem to notice the obvious change of topic (we were talking about his recent trip to London). “It’s a mess,” he immediately said. “Why?” I prodded. “Weren’t you super pro the current government?” “Yeah, yeah,” I was, he rushed. “But nothing has changed. Corruption is still an issue. The economy is in a mess. It was all just a bunch of tall promises in the end.” Yash then looked straight at me and added, “And what’s the worst? I can’t order a steak at a restaurant anymore.”

There we go. No mention of Dadri or Una, no mention of Muzaffarnagar or Mewat.

The problem was steak.

To be fair, the real answer lay in the fact that nothing has changed. My generation truly believed that change was around the corner -- that the economy would boom, that bullet trains would be a reality, that India would be this great power we could boast about. None of that happened, and -- fickle as we are -- we drifted away. Morality, unfortunately, didn’t figure in the scheme of things, but we have -- it seems -- taken offence to the empty promises.

The question that I turned to next was -- how does this feeling translate outside of the very niche (read elitist) sample group that my Facebook friends list forms?

What do millennials, say in villages or towns in UP and Bihar and Maharashtra, think of the current scenario? After all, the younger generation outside of the cities formed a key vote base for the current government, helping the BJP come to power. Are they as disappointed? Has there been a shift? And if so, why?

While I don’t know the answer to the above questions, I am reminded of an interaction I had with a group of young men somewhere in rural Bihar before the state elections recently. “Will you vote for the BJP?” I asked. “No,” they said, surprising me with their resoluteness. “Why?” I probed. “They are liars. They told us open bank accounts and we’ll transfer money into each account opened. We sold our goats to open the accounts. Months later, not a penny has come in.”

Judging by that (very skewed and limited) sample, this feeling of disappointment does seem to transpire. While amongst Delhi’s elite it manifests itself in the inability to order steak, in rural Bihar, it stings at the realisation that promises are often just that. In the end, whether in New Delhi or Samastipur, Bihar -- the plate is left empty.