The Great Discovery

Till 1997 Sunita Dwivedi was just another journalist. Then her childhood experiences caught up with her and she decided to further polish her passion for Buddhism. That primordial desire led her to a fascinating discovery of the appreciation that people have for the wisdom of the Buddha also outside of South Asia.

After all Sunita was born in Kushinagar, a sleepy eastern Uttar Pradesh district where Buddha delivered his last sermon. She grew up breathing Buddhism and later in life she decided to arm herself with a camera and to take to the road with little except the fragrance of the Buddha as guide.

The first journey of this author, traveller and researcher was to Nepal.

“Apart from the metalled roads that ran through the borders at Bhairahawa and Birdpur, there were river and mud tracks that led from the villages of Kakrahawa and Koilabasa along the Buddha marg into Lumbini where on a Vaisakha Purnima, the Great Buddha was born over 2500 years ago,” writes Sunita in Buddha in Central Asia: A Travelogue.

On the way she found that the geographical spread of Buddhism went far beyond the borders of India. Over centuries it had spread against the wind, the mountains, over the seas and across the horizon. As Sunita kept going she discovered new pathways on the gigantic network of the Silk Routes, reaching desert and other settlements of Central Asia and to the faraway land of China.

For Buddhism had traveled across the giant Himalayas to the heights of the Pamir and the Tien Shan. As far as the valleys of the Ili, Lepsi, Karatal, Talas, Talgar and Sumbe rivers in Kazakhstan and the Chuy river valley and around Lake Issyk Kul in Kyrgyzstan.

She found Buddhist centres, although in ruins, not only in the green valleys of Ferghana along the Syr Darya in Uzbekistan and along the banks of the Oxus and its tributaries in Tajijistan but also in the hot deserts of the Karakum and the Taklamakan.

She delighted in the discovery that the origin of the name of Bihar in India and the ancient city of Bukhara in Uzbekistan is perhaps from the same source of the Buddhist Vihara. She walked on the same mud tracks and pebbled pathways that still connect India with Nepal and she witnessed populations here continue the timeless act of trading grains and vegetables with each other. However she also faced the many iron walls erected by human beings in the name of patriotism and nationalism that keep people divided not only of this region but societies around the world.

The ancient routes out of India to its north western regions now in Pakistan that lead towards Afghanistan and other countries of Central Asia are shut today to common travelers.

The author is nostalgic for times when village markets had thrived on the border regions of South Asia, China and Central Asia and people had walked back and forth into neighbouring lands without fear of each other.

The regret is for the loss of those strands of the Silk Road that had once appreciated, and held together diverse cultural ideas like Buddhism.

It was less in capital cities and certainly not from behind closed door meetings that ordinary citizens had once exchanged ideas and faith. The intoxicating fragrance of the dhamma rose from the land of India was introduced by people to people on streets and spread far and wide along open routes.

It is along the southern Silk Road dropping from China and passing through the north eastern regions of India that the Mauryan emperor Ashoka is believed to have traveled to the Yunnan capital Talifu in the 3rd century before the birth of Christ. Here, he is believed to have married a Chinese princess Chien-meng-Kui, whose descendants ruled over Yunnan.

Following in the steps of monks who over centuries survived scorching deserts, lush meadows, dry steppe lands, snow capped mountains and gushing rivers valleys, the author realises that it is Central Asia that had showed the way to the world.

Central Asia had provided ardent disciples of the Buddha who on returning to their lands built the first stupas above relics of the Buddha. Many of the first missionaries carrying the message of the Buddha were unrivalled native scholars like the great King Devmitra, Milind and Kanishka who belonged to Central Asia much much before modern societies learnt to spell the word multiculturalism and coined the phrase global village.

And certainly before goons let loose by local nationalists were allowed to declare every Indian unpatriotic except themselves!

Already author of Buddhist Sites of India and In Quest of the Buddha: A Journey on the Silk Route, Sunita's latest book is a befitting tribute to Buddhism but also to a return to times when people had mattered more than passports and visas.

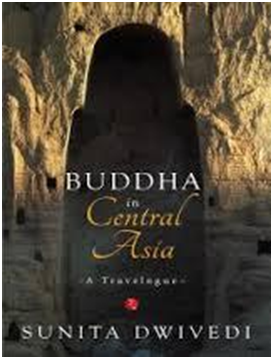

Buddha In Central Asia: A Travelogue by Sunita Dwivedi is published by Rupa, 2014