Javed Akhtar’s Jaadu On The World of Culture

Only when he was old enough to go to school that Jaadu became Javed

His humour is sunshine warm. His views on love and life are often waterfall fierce, but sometimes feel like molten honey. His politics is to call a spade a spade while his poetry remains achingly romantic. Whether it is about politics or poetry, he has been weaving magic with words for nearly half a century.

After all he was christened Jaadu (magic) although he is better known to the world as Javed Akhtar.

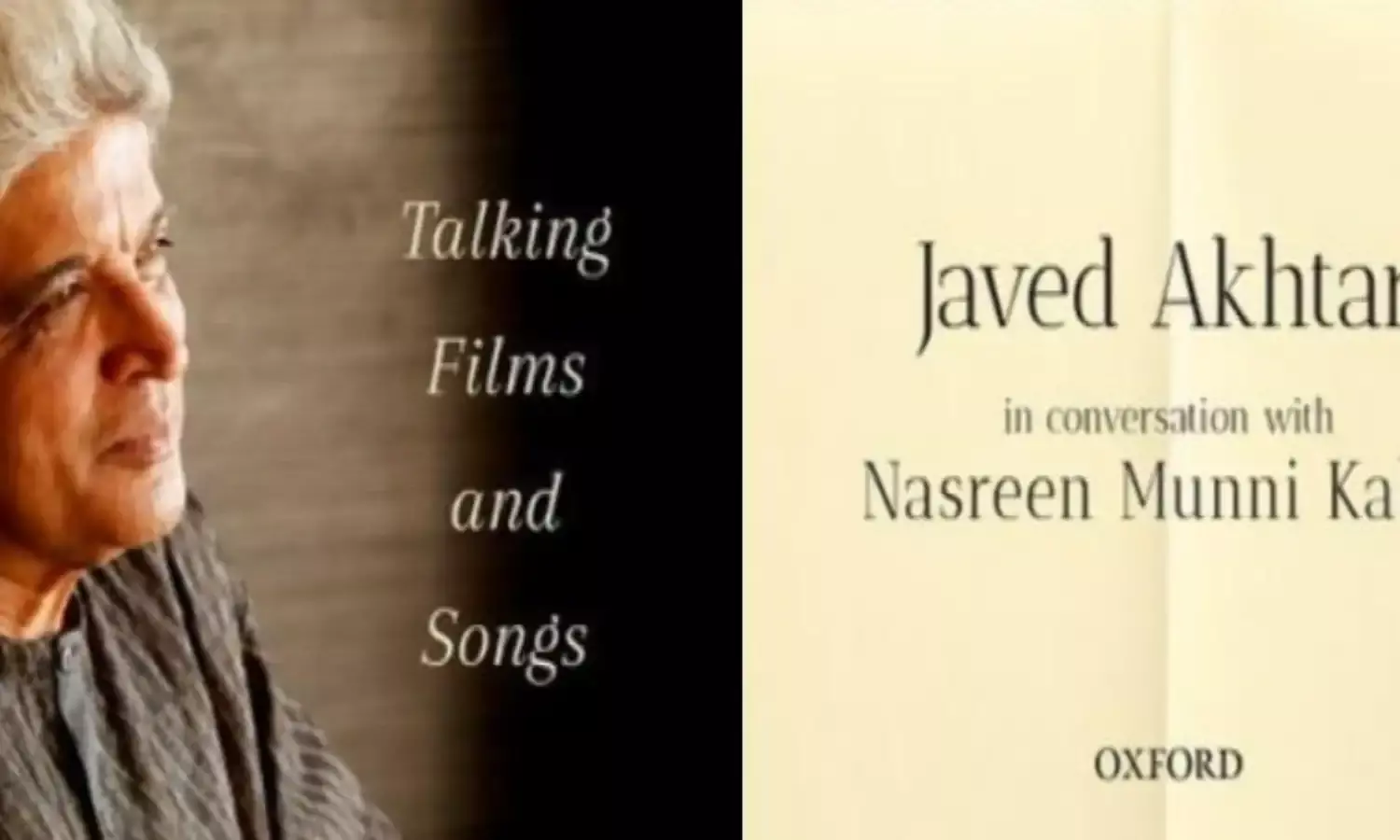

In a New Year gift to his fans, the Oxford University Press has released an omnibus edition of two earlier books called Talking Films: Conversations on Hindi Cinema with Javed Akhtar from 1999, and Talking Songs released in 2005 on his 60th birthday.

Well known documentary film-maker Nasreen Munni Kabir has put together these books after long conversations with Javed that began nearly two decades ago. Nasreen Munni says in the preface of this combined version titled Talking Films and Songs.

Any subject repetitions and overlaps in Talking Films and Songs have been removed and minor updating has been undertaken. Even though the conversations are about an earlier era, Javed Akhtar’s thoughts and ideas are just as relevant today, and I am sure they will remain so in times to come.

Apart from interesting information on films and songs this book also gives a grand list of incidents that have perhaps contributed to the elevation of Javed Akhtar as one of the most eloquent voices in India today.

After his birth on 17 January 1945 he was called Jaadu from a word chosen out of lamha lamha kisi jadu ka fasana hoga…a line from a poem written on the wedding of his parents by his father Jan Nisar Akhtar who had once hoped that every moment of his married life with Safia would be a magic experience.

It was only when he was old enough to go to school that Jaadu became Javed, a more formal name for official purposes. His aversion to organized religion can be traced back to his atheist father reading out the text of the communist manifesto into his infant ear instead of the traditional call to prayer.

For Javed, humour is serious business and he regrets that we have been incapable of nursing a Charlie Chaplain kind of character in our midst.

I don’t know why we have a strange highbrow attitude towards comedy in our county. We think humour is cheap and inferior. I think we have been deprived of happiness and pleasure for a very long time, so we think that anything that can make people happy or can provide pleasure is either sinful or taboo, or of inferior quality. It is believed that things that are respectable have to be bitter, unpleasant, heavy and boring. I don’t know why.

He enjoys a great gift of the gab and credits the talent of storytelling and poetry writing to his eternal love for books. The more you read the better writer you become, he says. Besides spinning tales is in his blood as he grew up in Lucknow where making up stories was once a thriving institution. Poetry was very much a part of his growing up years. As a child he heard Josh recite poetry and Jigar too. He heard Firaq and Makhdoom and was fortunate to know Sahir, Ali Sardar Jafri, Kaifi and Majrooh very well, and his maternal uncle Majaz. By the time he was 12 years old he had memorized hundred of couplets by heart and recited them whenever he wanted to.

In his youth his favourite author was Ibn-e-Safi.

He was very good in every way-his style of writing, his diction, his sense of humour…He used to write thrillers like James Hadley Chase or Earl Stanley Gardner. He was the first person that I am aware of who had a kind of Western sophistication in his writing and combined it with all the richness of the Urdu language. He had the understatement and crispness that you find in American novels.

He is sorry that Urdu was sacrificed at the altar of the two-nation theory. This is despite the fact that Urdu is living proof of a truly composite culture. Languages don’t have religions-languages have regions. But politicians and communal politics decides otherwise. Urdu is resilient because it is the language of the people. You cannot curb people, and despite all the bias and the prejudice against Urdu, it has survived.

In the last century or so north Indian urban society had developed a certain way of life linked to Urdu irrespective of the religion of the community. When you throw out the language, the culture goes with it and a void is created, which has not been filled by anything else.

Javed points out:

Europe is predominantly Christian, but it’s made up of different nations. For some illogical reason, it was decided in India during the last hundred years that religion is the basis for nations. Extreme right-wingers, both Hindu and Muslim propagated this theory. We’ll cut the story short, because it is a saga in itself- but this kind of thinking culminated in the Partition of India on religious grounds. Since they had decided that Hindus and Muslims are two different nations, they had to deny any shared culture or heritage. There was a deliberate attempt to create a false separation between their common histories and cultures. The extreme-right Hindus called Urdu ‘Muslim’ and the extreme-right ‘Muslims’ also called it ‘Muslim’.

It was at the age of 19 years that Javed decided to work with Guru Dutt but a few days after his arrival in Mumbai, one of the country’s greatest film directors passed away. Young Javed felt orphaned and he took on odd jobs in the film industry to survive. His struggle continued till the spectacular critical, and box office success of Zanjeer, the 1973 film starring Amitabh Bachchan. His partnership with Salim Khan as a scriptwriter began around 1971 and continued till 1981 after which he devoted more time to poetry, and to writing lyrics of film songs.

The last word on Jaadu is reserved here for Shabana Azmi, who is not just his wife but also his beloved. In the last chapter of the 172-page book Shabana writes:

He hardly ever talks about his work, but when he does, it is with such astounding clarity that I listen in rapt attention and learn something new each time that I hear him.

Talking Films and Songs

Javed Akhtar in conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir

Published by Oxford University Press, 2018.