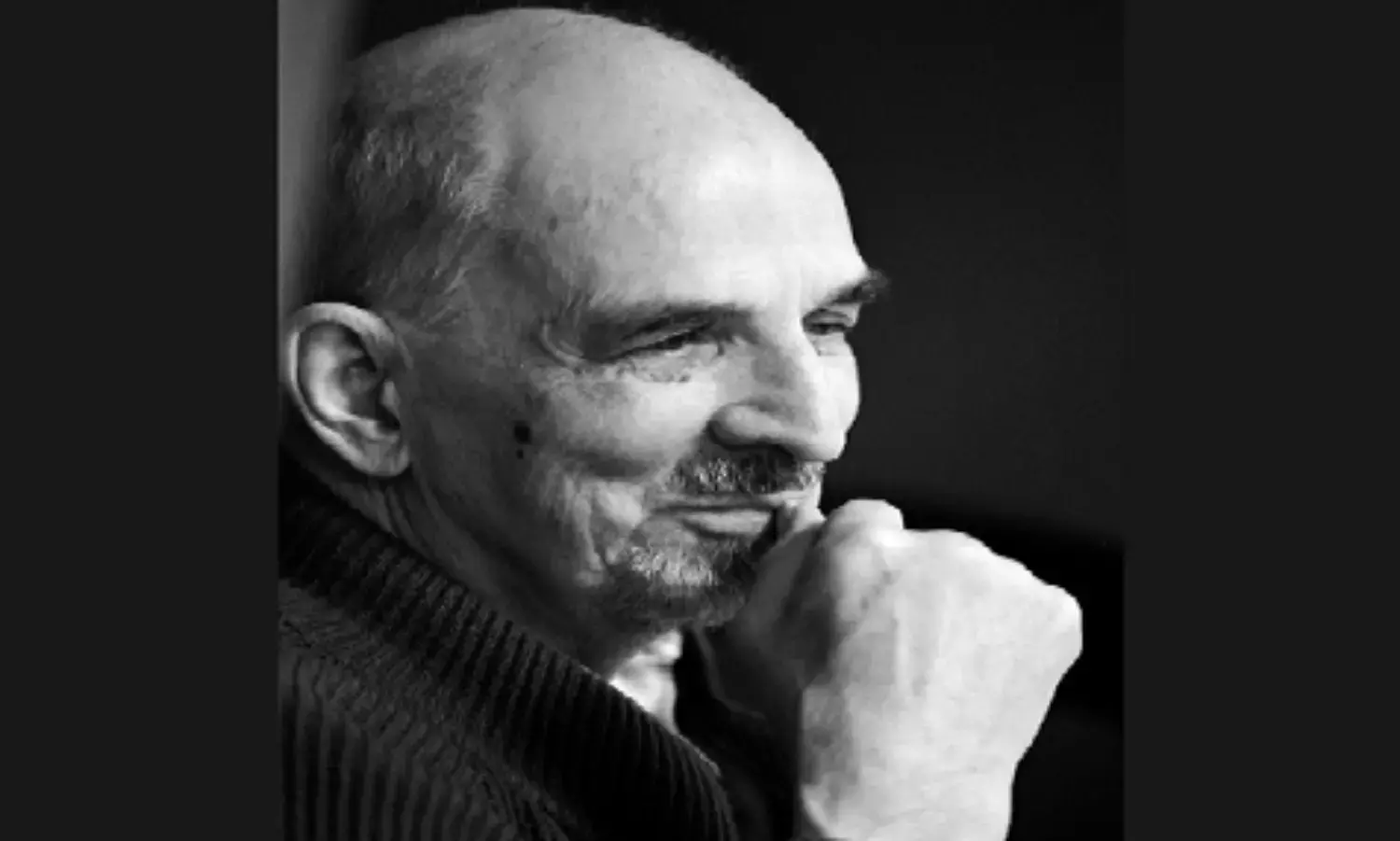

The Ingmar Bergman Story

Centenary tribute

“Filmmaking is for me a necessity of nature, a need comparable to hunger and thirst.”

Ingmar Bergman

Is Ingmar Bergman, as critic and scholar Trailokya Jena said, “a link between the past and the future?” Yes, he is.

But his creative mind reaches much beyond the past and the future because his films, rich as they are in interweaving of dreams and reality on the one hand and emotions and nostalgia on the other, or God and no-God also, can be interpreted as an ode to the ideology of infinity.

His films are replete with violence and harmony, with love and hate and revenge that could be read politically or historically, or even sociologically with heavy underpinnings of the psychology of dreams. Not one of his 62 films is like the others. His films defy genre because they can all be reduced to the single genre of being labelled a “Bergman” film and that completes the picture. Or does it, really?

In a series of interviews that are as mesmerizing as his films, going back to his childhood, Bergman said how he was such an incorrigible dreamer that with time, for him, the line between the real world and his dream world were so blurred that he failed to discern any difference between the two and was often pulled up and even punished by his very strict, very conservative Catholic father because they felt he was lying all the time.

These dreams grew along with the small boy of five who loved to “listen” to the rays of the morning sun, from under the dining table watching with wonder, the sunlight falling through the window and seeping right under the table where he waited for the sun to reach. The bells in the cathedral close to his home would begin to ring and hearing those chimes, the little boy would just know that the rays of the sun would leave the floor, the room and climb along the wall of the room where a picture of the city of Venice hung on the wall.

Slowly, the church bells mingled with the melodies of a waltz while the waters in that picture rippled and the sounds of humanity could be heard, all this mingling happily with the sweet melody of the waltz and the ring of the church bells. Was that the beginning of the passion for the moving picture with sound and music and characters and stories?

It was his grandmother alone who understood what went on in this little boy’s mind. And the boy knew that all these moments of happiness were too fragile to last – they would break like delicate glass into smithereens the minute his very strict father, a Catholic priest, for whom, Christianity and the Chrurch meant everything would enter the scene.

His centenary is being celebrated across the country and beyond in the only way it should be celebrated – screening of some select films directed by Bergman himself. He married five times and each, except the last one ended in divorce while the last one ended tragically with the death of his wife who had cancer. Why so many marriages and that too, with significant women? Because he was already married to theatre while cinema was his raging passion. He once said, “The theatre is like a loyal wife, film is the big adventure, the expensive and demanding mistress – you worship both, each in its own way.”

“A Bergman film is, if you like, one twenty-fourth of a second metamorphosed and expanded over an hour and a half. It is the world between two blinks of the eyelids, the sadness between two heart beats, the gaiety between two handclaps,” said Jean-Luc Goddard once. With nine individual Oscar nominations and three films winning the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, Ingmar Bergman won every conceivable and coveted film award on the planet.

With his massive repertoire of around 62 films, most of which he wrote, married to his versatility and the rich tonal, audiovisual and aesthetic quality of his works, Bergman certainly merits an auteur criticism. But like Satyajit Ray, it would be both be impossible and unfair to ‘bracket’ all his films and subject them to the same measuring rod of auteur criticism. His evolution is defined by markers that divide the various phases of his career in filmmaking. This suggests a study of his entire works done in varied volumes, each devoted to a single phase.

Every frame of his films are so beautifully choreographed that deeply inspired by this cinematographic choreography, noted Swedish choreographer Alexander Eckmann who, along with some prominent dancers of the Swedish Ballet made a documentary exclusively focussed on Bergman’s choreography which was screened at the Cannes too. The filmmakers insist that choreography was prominently present in every frame in the way the characters nodded their heads, their body language, their hand movements which created a beautiful choreographic image that has left its imprint on cinema forever.

Born in Uppsala, Sweden, to Karin and Erik Bergman, minister and later chaplain to the King of Sweden, Ernst Ingmar Bergman grew up surrounded by religious imagery and discussions. He grew up surrounded by religious imagery and discussion. His father was a conservative parish minister with extreme-right political sympathies and a strict family father. Wetting the bed for instance, invited being locked up on dark closets for hours, while his father would preach away in the pulpit and the congregation prayed, sang or listened.

These early memories come across in his autobiography Laterna Magica. As a boy, Ingmar was attracted by “the church’s mysterious world of low arches, thick walls, the smell of eternity, the coloured sunlight quivering above the strangest vegetation of medieval paintings and carved figures on ceilings and walls. There was everything that one’s imagination could desire – angels, saints, dragons, prophets, devils, humans,” he wrote in his autobiography.

For Bergman, to be alone meant to ask questions and to make films meant to answer those questions. Bergman insisted that through his films he tried to portray the truth and truth for him, was neither a monolith nor an absolute. It was truth as he, the director Bergman perceived it. His entire volume of work, has qualitatively and cinematically proved that truth is always “new”, “personal” and whatever is profound and deep-rooted is the truth.

The three very abstract and yet so concrete films The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries and The Silence define the power and incision that became the signature of this director. These three films, according to many film scholars, constitute an independent trilogy of films with man’s relationship with Death where man is engaged in a game of chess with Death itself (The Seventh Seal), man’s relationship with himself (Wild Strawberries) and man’s relationship with others (The Silence) where God is conspicuous either with His presence or with His absence.

Of the 15 feature films he directed between 1945 and 1954 received very mixed reactions in Sweden. A A March 1946 review of Crisis, quoted by Birgitta Steene, in ‘“Manhattan surrounded by Ingmar Bergman”:, his first film as director, argued: “There is something unbridled, nervously out of control in Bergman’s imagination that makes a disquieting impression. He […] seems to be incapable of keeping a mental level of normalcy. What the Swedish cinema needs in the first place are not experimenters, but intelligent, rational people.

Bergman usually wrote his own screenplays after having pondered over them for months and sometimes, even years before he began the actual process of writing down the script. His earlier films are carefully structured, and are either based on his plays or written in collaboration with other authors.

Bergman confessed that in his later works, he allowed his actors to do things differently than he had conceived but these often resulted in disastrous results. With time, Bergman increasingly let his actors improvise their dialogue. In his last films, he wrote just the ideas informing the scene and allowed his actors to determine the exact dialogue.

Bergman's most challenging questions his cinema so powerfully and disturbingly raises have not only not been answered; looked at afresh, they could be more pressing than ever. Rather than experiments overcome by newer progressive models, now that the era of modernism is deemed to have passed, this work seems more daringly etched and radical then ever.