Communalism Is a Donkey Wearing a Lion Skin

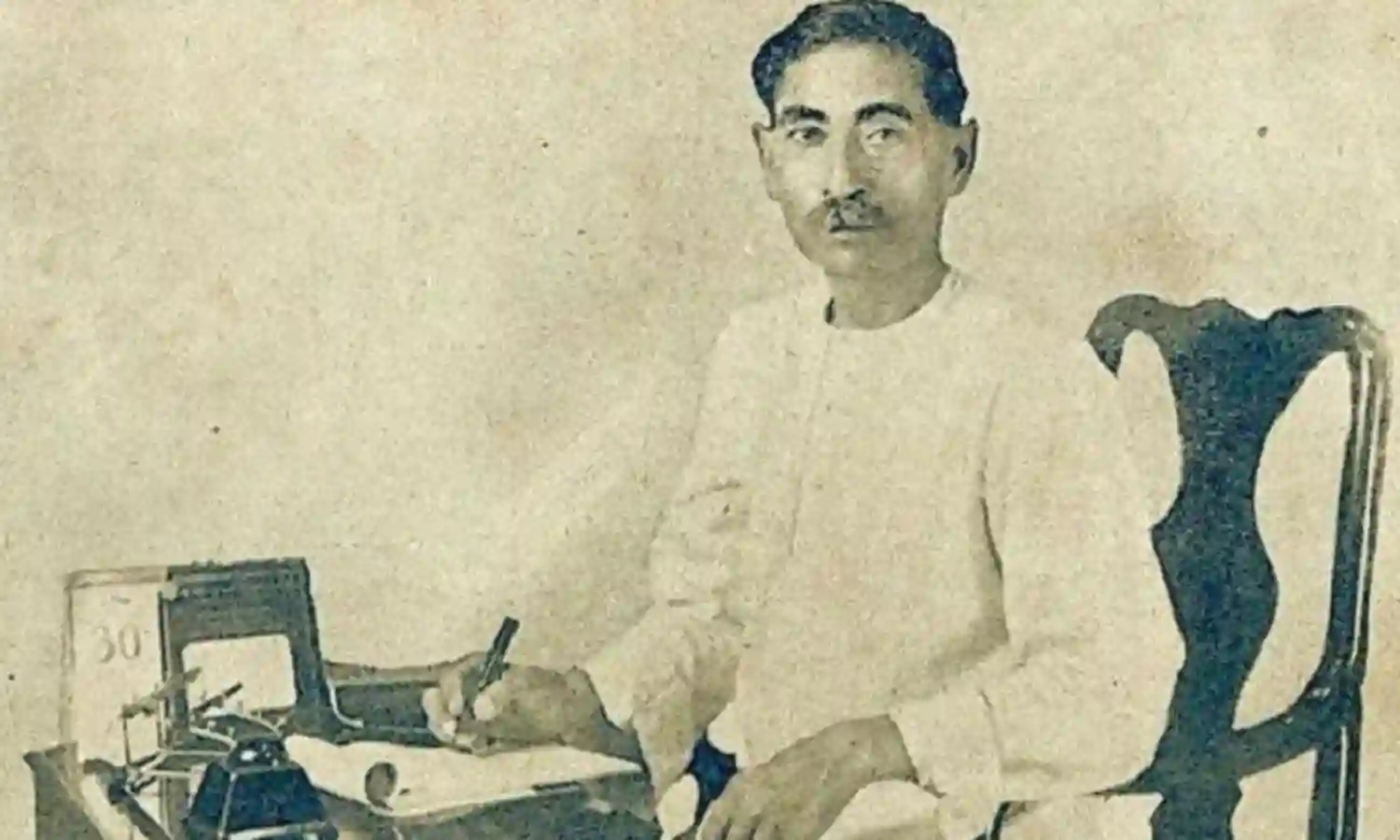

Remembering Premchand on his death anniversary

Perhaps Indian society is best described as the Great Indian Tamasha, for there is never a dull moment to keep the tamasha from going on. And perhaps the best fodder for this tamasha is the holy word, ‘sanskriti’. Sanskriti or culture is a word that is whipped up time and again in our society. Strangely, it is used by forces who on being asked the definition of Bhartiya Sanskriti, often find themselves in a fix. With elections approaching in many states later this year and the big fight next year, we can expect to hear the word sanskriti increasingly often, and the impending danger to it from forces invisible.

In such times, I am obliged to remember the great Munshi Premchand on his death anniversary, whom I find more relevant today than ever before.

It is sad to see a large number of urban youth becoming virtual custodians of their Sanskriti and Tehzeeb on social media platforms. It would be inappropriate simply to call them trolls, because if one gives even a cursory read of the language they use, it would amount to hate speech, verbal violence and provocation.

The army of such self-proclaimed custodians of sanskriti and tehzeeb is not limited to any one religion.

In an essay titled ‘Saampradayikta aur Sanskriti’ (Communalism and Culture), which Premchand penned in 1934, he talks of the frivolous yet vituperative nature of the forces which deploy sanskriti or culture as a pretext for furthering their own sinister communal motives. He says, 'Like the donkey which wore the skin of the lion to impose its dominance on the animals of the jungle, communalism comes in the guise of culture.'

Munshi Premchand’s incisive essay gives a rational and lucid analysis of the nature of the forces that use ‘sanskriti’ to stir up emotions along communal lines. He writes, 'The Hindu wants to keep his culture safe until the day of judgement, and the Muslim, his own. Both have considered their cultures to be untouchable until now. They have forgotten that now there is neither a Hindu culture anywhere, nor a Muslim culture, nor any other culture. Today there is only one culture in the world and that is economic culture; but even today the Hindus and the Muslims go on harping about culture, although culture has no relationship with religion.'

Here is a writer who decades ago elucidated that it was solely economics that was a culture common to all. A north Indian Hindu is starkly different from a south Indian Hindu in food habits, attire and language, and the same goes for a Muslim. Culture can never be associated with religion; it is purely a category demarked by a shared region. And for a terrain as diverse as India, there cannot be one version of ‘Bhartiya sanskriti’ or so-called Islamic tehzeeb, that would be shared by everyone from a particular community.

Premchand highlighted the frivolity and hypocrisy of such forces who use the weapon of culture to incite people. The realities haven’t changed much today, or even hold truer in the times we’re living in. Premchand’s words are bound to make one think when he says, 'I fail to understand what this culture is that communalism is so hell-bent on protecting.'

Truly, one wonders about the role such self-appointed saviours of culture take upon themselves, in order only to divide our society along communal faultlines. He writes, 'The guardians of Hindu and Muslim culture are those gentlemen and those groups who do not have faith either in themselves, or in their countrymen, or in the truth, and therefore, perpetually feel the need of an entity which will act as the arbitrator in their quarrels.'

As the country braces itself for the much awaited 2019 general elections, the crop of newspapers will carry more headlines related to the Ayodhya conflict, or of immigrants termed ‘termites’, and thus the need to safeguard ‘sanskriti’. Yes, that unknown entity which doesn’t have a definition when put into an Indian context, yet remains the basis for inciting communal hostility.

Although Premchand physically died over eighty years ago, on October 8, 1936, he is still alive in his writings. This writer shares the agony of the ‘Upanyaas Samraat’ (Novel King), who was a visionary and kept a close watch on the society in which communalism continues to thrive, thus blinding people to the economic woes of the country. 'Communalism marches on, having shut its eyes to the people’s economic problems, so that their dependence remains everlasting.'

It’s high time we connect the dots in our times, and be wary of the forces against whom Premchand cautioned us.

(The writer acknowledges Sanjukta Poddar for her translation of this essay).