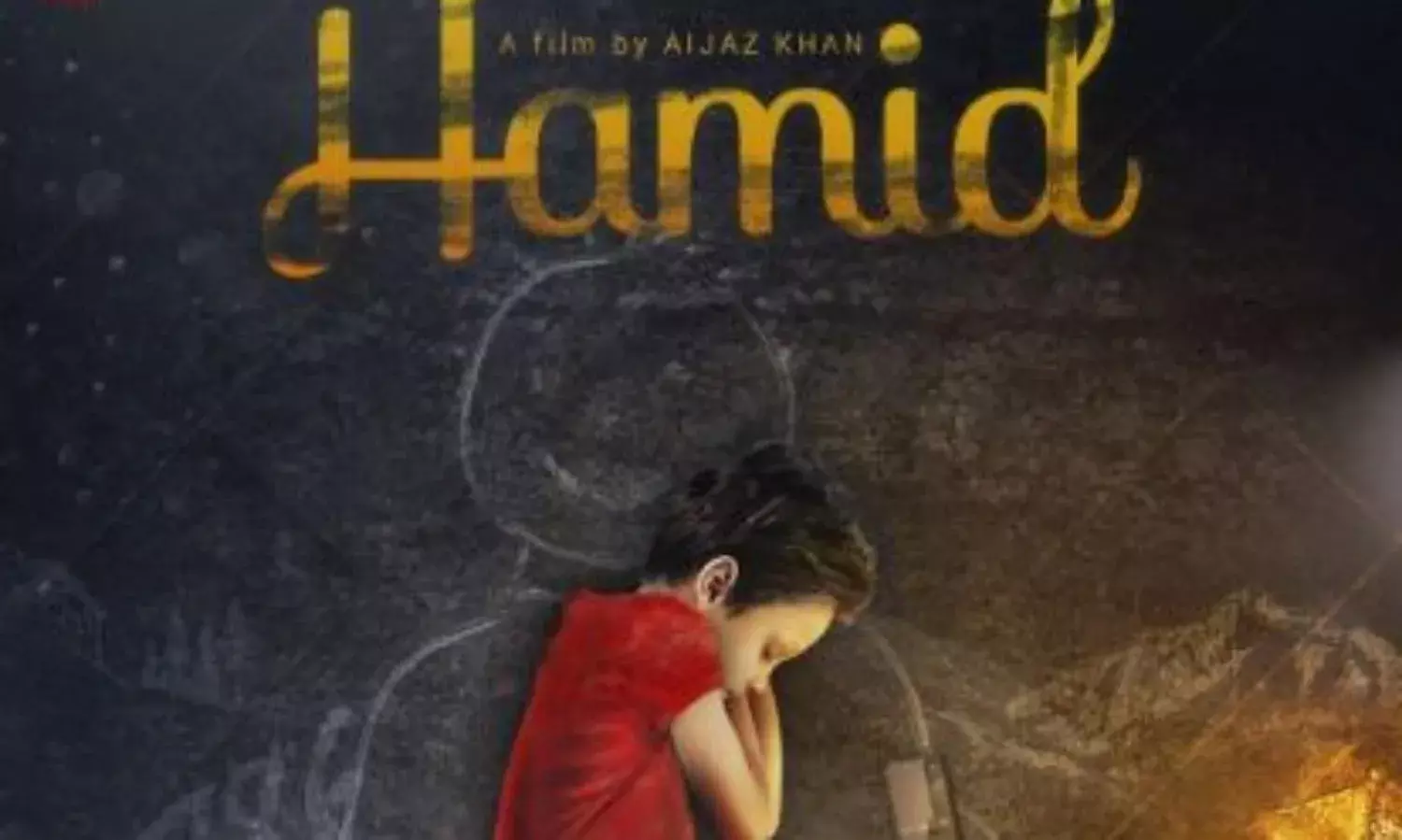

When Hamid Found a Way to Dial Allah

A movie that reflects reality

This was the title of a documentary film I saw five years ago made by Kashmiri film maker Iffat Fatima. Last night I with two friends saw the film Hamid made by Aijaz Khan. For me there was a beautiful continuity between these two films. Both were result of sensibilities of two chasm deed gawahs (eye witnesses) of the tragedy called Kashmir

It happened like this. A friend with who I share love for films said ‘You have to see this film Baji. It wont last in the theatre. There were only five people when I saw it.’ As it happened when I saw it two days later, I counted only five.

The film opens with Rehmat leaving his carpentry workshop after a day’s work. He is stopped by security. ‘Who? What? Show?’ His box of tools is searched and his diary in which he pens his craft along with poems which he composes from time to time. ‘Read’ barks the jawan. In a voice tremulous with fear he reads. The meaning of his poem is adversely twisted by his interlocutor and pages are torn.

This exact scene played in my mind when I was visiting Kashmir 20 years ago. I was returning one night post dinner in a car with the most respected family of Kashmir. Our car was stopped and torches were flashed in our eyes with same questions. I was angry. How dare they stop Kashmiris from moving freely on their own land?

How dare they stop me, a Kashmir born, from moving freely in my janambhoomi? So I stepped out in the dark while the torch beam sized me up. ‘Sorry Madam’. That was 20 years ago. I was a sari clad ‘Indian looking woman’ (whatever that may mean). I was not a humble young man with a namazi cap holding an old toolbox.

Rehmat ‘disappears’ when he returns to his workshop to fetch batteries so his 7 year old son Hamid could watch the match on TV. The word ‘disappeared’ has become embedded in hearts, minds, and vocabulary of Kashmir. It has one meaning; young men who go out of their homes or are pulled out of their homes never to return. No one knows whether they are living or dead.

Their families sit endlessly on benches in police stations, grasping much fingered files, which would reveal (they hope) whereabouts of their loved ones. Husbands, sons, brothers… a word, a sign, a breath. They wait. Are they alive, are they dead? We shall wait but shall we get closure? The film Hamid captures this question through the eyes mouth hands feet of this small boy, who makes us laugh, cry, wince and crumble.

Hamid finds a way to dial Allah. The numeral 786 stands for Bismillah Ar Rehman Ar Rahim. He configures this number on an old phone he finds in his father’s tool box. The number connects him to a CRPF jawan Abhay Kumar. Through this strange connection the film narrates the multiple layers of the Kashmir conundrum. The killings, stone pelting, disappearances, broken families, mental illness, jawans, humiliation, loneliness, militarisation, stoicism, defiance, depression. All of this is set is a landscape that is achingly exquisite.

Man and boy is an old theme which always touches the right chords. Here is a man on the brink of a break down, suffering loneliness and longing for his far off home. One day his phone rings and brings to him this child-voice who addresses him as Allah Miyan. 786 repeated and configured could only be the telephone number of Allah is the logic of the boy.

The child has only one demand of Allah, ‘Send my Abbu back’. Ishrat, his mother is played by Rasika Duggal who was unforgettable as Safia, the wife of Saadat Hasan Manto, in Nandita Das’s remarkable eponymous film. The boy and the man never meet. But their tender connection through wires brings them close to what can only be described as bond of love. Ridiculous as it sounds, considering their juxtaposed worlds.

Their long distance trust melts away when during a stand off between the people and the forces Abhay reveals to Hamid that the father is dead and he is not Allah so can never bring him back. The boy asks him, ‘Are you our dushman?’ His answer ‘Yes and you are ours’. The boy’s world crashes as he pelts his first stone and buries his mementoes of his Abbu in a small grave.

At that time, his mother, Ishrat is sitting with women who have been holding vigil every month for 20 years for their loved ones who have ‘disappeared’. For Ishrat this silent grieving becomes cathartic. The intense grief which is stone-stuck in her heart for one year flows out of every fibre of her being even as her fellow protestors say ‘We never cry, we never say the word dead’. The first time after her husband walked out of the house, she is able to cry holding little Hamid in her arms.

The last scene is of the shikara which Hamid has painted red as his father wanted. Mother and son ride the boat on the sombre waters of Dal, while the twisted wires all around remain grim symbols of the uncaring callous state. That is where the film ends on a sliver of hope. For me it was the exquisite song, an old Kashmiri folk song Hukus Bukus sung by father and son riding a bicycle in happier days, which made me recall the Kashmir I knew as a child and which no Kashmiri would ever know again.

This film rather than the crass biopics which are assailing our sensibilities today is what we all, I mean all of us Indians, should be watching at this time.