Supreme Court Gives Dissent a ‘Designated Place’

One more restriction on the right to assemble peaceably

The Shaheen Bagh protest began on December 14 last year primarily against the Union government’s citizenship proposals and grew for 101 days gaining both national and international attention.

At the time some persons approached the Supreme Court alleging blockage of a stretch of road by the sit-in protestors at Shaheen Bagh.

Although the protest was wound up on March 24 in the wake of the pandemic, the apex court took up the matter for hearing on September 21.

It may be pointed out here that there are already enough judicial pronouncements, guidelines and SOPs to guide governments on how to handle protests, and the Supreme Court could well have simply directed the authorities to strictly follow these in future.

Recently, in the case of Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan v. Union of India & Another (2018 17 SCC 324) while dealing with a similar situation and grievances, the court discussed the matter in detail and also issued guidelines to the Delhi Police.

In the Shaheen Bagh case, the Supreme Court gave its verdict on October 7. While recognising that the reliefs sought by the petitioners had already been realised it further decided to “pen down a few more lines for clarity on the subject on account of its wider ramification”.

Despite recognising the right to protest, it decided to confine protests to “designated places alone”. This adds one more restriction to citizens’ fundamental right to peaceful assembly under Article 19 of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court, while balancing the right to protest and people’s right to mobility, referred to its earlier judgment in the case of Himat Lal Shah vs. Commissioner of Police (1973 1 SCC 227) citing these lines authored by Justice K.K Mathew:

“Streets and public parks exist primarily for other purposes and the social interest promoted by untrammeled exercise of freedom of utterance and assembly in public street must yield to social interest which prohibition and regulation of speech are designed to protect. But there is a constitutional difference between reasonable regulation and arbitrary exclusion”.

Without saying anything more, here are paragraphs 60 and 61 of that judgment in full, of which the court cited the last few lines:

“60. Freedom of assembly is an essential element of any democratic system. At the root of this concept lies the citizen's right to meet face to face with others for the discussion of their ideas and problems - religious, political, economic or social. Public debate and discussion take many forms including the spoken and the printed word, the radio and the screen. But assemblies face to face perform a function of vital significance in our system, and are no less important at the present time for the education of the public and the formation of opinion than they have been in our past history. The basic assumption in a democratic polity is that Government shall be based on the consent of the governed. But the consent of the governed implies not only that the consent shall be free but also that it shall be grounded on adequate information and discussion. Public streets are the 'natural' places for expression of opinion and dissemination of ideas. Indeed it may be argued that for some persons these places are the only possible arenas for the effective exercise of their freedom of speech and assembly.

“61. Public meeting in open spaces and public streets forms part of the tradition of our national life. In the pre-Independence days such meetings have been held in open spaces and public streets and the people have come to regard it as a part of their privileges and immunities. The State and the local authority have a virtual monopoly of every open space at which an outdoor meeting can be held. If, therefore, the State or Municipality can constitutionally close both its streets and its parks entirely to public meetings, the practical result would be that it would be impossible to hold any open air meetings in any large city. The real problem is that of reconciling the city's function of providing for the exigencies of traffic in its streets and for the recreation of the public in its parks, with its other obligations, of providing adequate places for public discussion in order to safeguard the guaranteed right of public assembly. The assumption made by Justice Holmes is that a city owns its parks and highways in the same sense and with the same rights as a private owner owns his property with the right to exclude or admit anyone he pleases: That may not accord with the concept of dedication of public streets and parks. The parks are held for public and the public streets are also held for the public. It is doubtless true that the State or local authority can regulate its property in order to serve its public purposes. Streets and public parks exist primarily…”

Now with the court deciding that protests should be in “designated places alone”, it was only appropriate that it should have indicated what sort of designated places these should be.

Left to the executive, they may well be in the outermost isolated area of a city, far removed from the public and the corridors of power, from the press and city centre, with Mother Nature the only audience.

The court should not have left it completely to the executive, which is known to misinterpret even the clearest court orders, to decide which places to designate.

The court also seems unhappy with the government’s handling of the protest, observing in para 20 that:

“In what manner the administration should act is their responsibility and they should not hide behind the court orders or seek support there from for carrying out their administrative functions. The courts adjudicate the legality of the actions and are not meant to give shoulder to the administration to fire their guns from”.

It further observes:

“We only hope that such a situation does not arise in the future and protests are subject to the legal position as enunciated above, with some sympathy and dialogue, but are not permitted to get out of hand”.

In all likelihood the executive will read the letter more than the spirit of these words, and more easily get away with any excessive use of authority or force in the garb of complying with this judgment.

The executive predilection to misread court orders and overdo things is not unknown. It was with the intention of not letting things “get out of hand” that the Hathras police and administration took it upon themselves to cremate the body of Manisha Valmiki against her family’s wishes.

It seems the Supreme Court has unwittingly rendered its firm shoulders to the executive to fire their guns from.

Protests erupt when people are muzzled. It may be mentioned that the women in Shaheen Bagh were not protesting for the heck of it. Old women, middle aged women, young girls were all there braving the chill of Delhi winter nights, not to derive fun out of the situation.

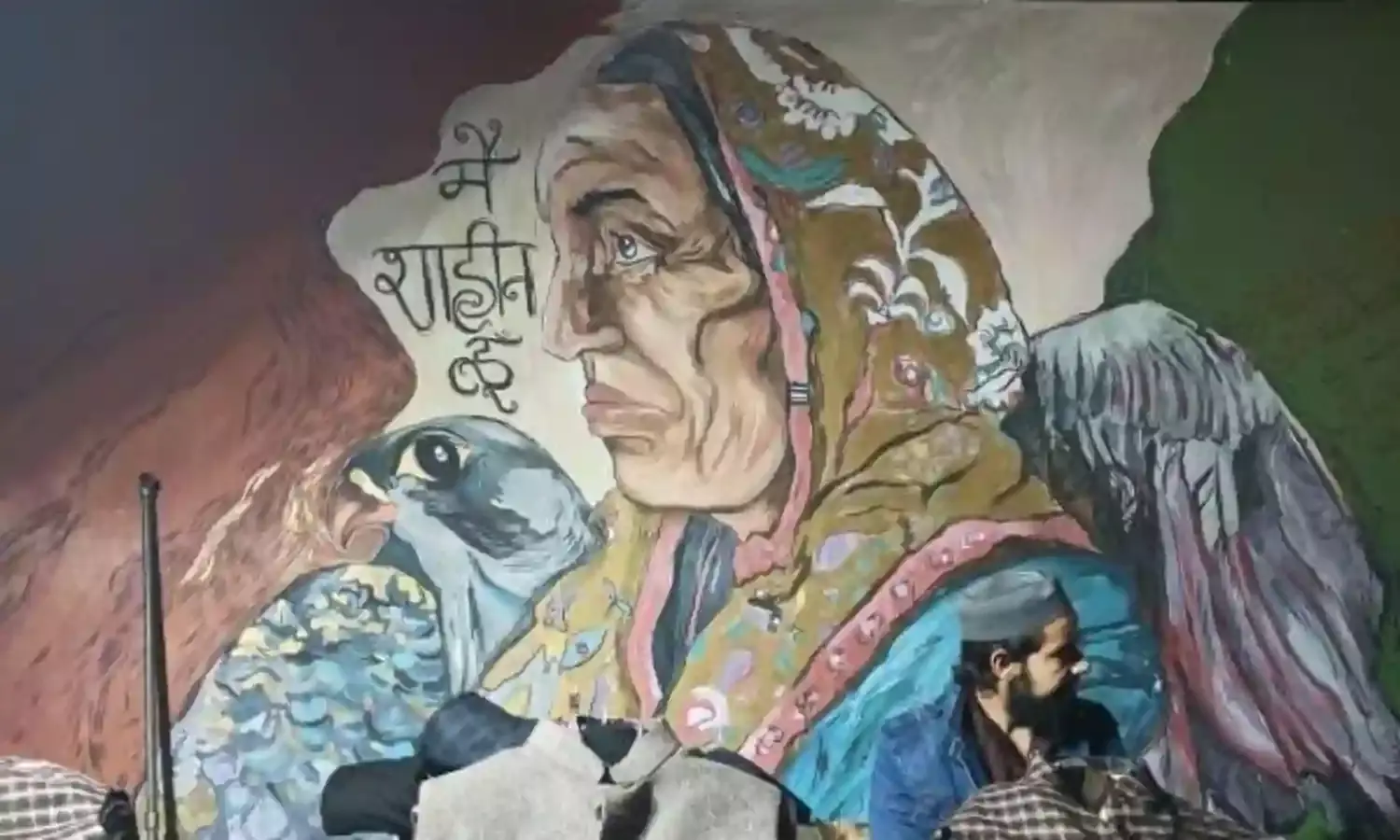

They wanted their voices to be heard but government was unresponsive. Bilkis Bi, at the ripe age of 82 years, opted to exercise her constitutional right to protest rather than to sit at home.

Bilkis Bi was included along with Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Time Magazine’s list of 100 most influential persons of 2020 because she courageously chose to get her dissent registered by participating in the protest.

But the Union government turned a blind eye to the protestors. It is displaying the same attitude to the farmers in Punjab and Haryana who are protesting against the farm bills recently passed by Parliament.

When the Supreme Court decided to “pen down a few more lines for clarity on the subject”, it should have also spared a thought for the role of protests and governments in a democracy.

But the verdict has come and the ball is now in the executive’s court, with a very wide scope to exercise discretion (and indiscretions).

The judgment quotes a famous line by Walter Lippmann, considered a father of modern journalism:

“In a democracy, the opposition is not only tolerated as constitutional, but must be maintained because it is indispensable.”

It is to be hoped that the executive will take this line as a guiding principle when handling the next protest in conformity with the Supreme Court judgement.

Amit Jaiswal is an advocate at the Punjab and Haryana High Court