The Trailblazer of Indian Cinema

The event was Star Guild Awards given for excellence in various aspects of cinema and television. The NSCI auditorium in Worli Mumbai was filled to capacity. A red carpet leading to the venue was receiving celebrities and film personalities while media was milling around the cordoned area. The scene was set for an Oscar type event presented by Wizcraft, event entrepreneurs who are famous for their super spectacular shows.

It was 16 January 2014. I had gone there for a reason which had nothing to do with the spectacle and glamour of the awards ceremony.

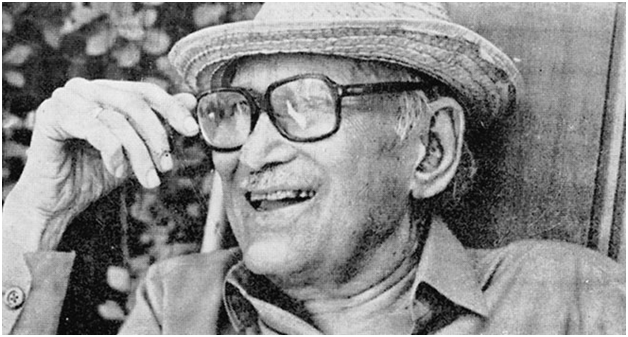

I had gone for a man called Khwaja Ahmed Abbas.

Abbas had arrived in Bombay in 1936, fresh with a BA LLB from Aligarh. Here he found work at the newspaper Bombay Chronicle as a film critic with a monthly salary of 60 rupees. During his life span of 72 years he wrote 73 books, produced, directed, and wrote 13 films, wrote stories dialogues and screenplays for 17 films and wrote Last Page of Blitz every week without fail for 45 years. He would have completed 100 years in June 2014. But what did all this have to do with Star Guild Awards?

To recall Abbas’s relationship with the Producer’s Guild, he had been an active member and one time President of the Guild. A few weeks before his death, he arrived at a meeting of the Guild directly from his hospital bed. Everyone was amazed to see him coming out of a taxi in his hospital kurta pyjama. On this day, 28 years later the Guild under its Chair Mukesh Bhatt had decided to honour him. In this instance, the industry was epitomised by one man who Abbas held dear; the most towering figure in history of films-- Amitabh Bachchan.

Abbas had given the first break to Amitabh in his film Saat Hindustani, produced in 1971. Much later when Amitabh was a big star and Abbas, as usual, was struggling to make socially relevant films, neither one of them forgot about the other. Abbas recorded his memory about the tall handsome boy-man who had come to him for a role, in his article called ‘Alif se Amitabh’ and Amitabh remembered him when Abbas was on his deathbed in a Bombay hospital and there were severe financial constraints for his treatment. But what happened at the Guild awards was a connection between the guru and shishya which transcended time and life. Amitabh institutionalised the work of Abbas in a manner that the world would not forget him, ever. The debt to a great man had been paid by another great man. It was nature’s perfect balancing act.

Suddenly the stage phantasmagoria darkened and a voice was heard, a voice which over the years has become the definition of sound. Amitabh was speaking of a man who gave a vision, a dream, and an ideal to Bollywood. He was a man who refused to compromise with commerce of films, also essentially the child, a Peter Pan who refused to grow up. He spoke of coming to Mumbai after chucking a steady job in Calcutta and coming with a request to Abbas in his small flat in Juhu. Abbas looked him up and down. ‘I am a victim of height excess’ Amitabh joked, but Abbas simply said ‘you are just the person I was looking for, you are perfect for my character Anwar Ali ‘Anwar’ revolutionary poet from Allahabad; you will become the 7th Hindustani we were looking for. You will have to start immediately. And one more thing, we can offer you no more than 5000 rupees; this is what the others are getting for the film. Yes or No?’

Amit recalled Abbas’s films right from Dharti ke Lal in 1943 to Shehr Aur Sapna about travails of urbanisation, which won the President’s Gold Medal after having been turned down by 14 financiers. He recalled Aasman Mahal about the crumbling feudal society in Hyderabad and clash between tradition and modernity. He spoke of Abbas as a trailblazer in Indian Cinema who used every medium, feature film, documentary, novel, short story and journalism for his message of a just social order. Cinema is India’s most powerful instrument for social transformation, Amitabh said, and Abbas was its mascot. No matter how poorly he did at the box office, he never gave up. Taking up the cause of the marginalised no matter who they were, his characters reflected the reality rather than celluloid dreams. Interspersed with this stirring speech were shots of films, blockbusters which Abbas wrote for Raj Kapoor—Awara, the iconic vagabond, Shri 420 lovable trickster, Mera Naam Joker, Bobby and finally Amitabh’s own—Saat Hindustani. There he was Amitabh on Abbas’s screen fighting for Goa against the Portuguese, alongside six companions from all parts of India who were strangers to one another before this mission made them one; not Tamil, Bengali, Bihari, Muslim, Hindu, Christian but just Indians, all of them fighting for India.

Having said all that could be said in his inimitable manner during an emotion packed 10 minutes, Amitabh on behalf of the Guild announced an award called the K A Abbas award for the most socially relevant film of the year. This year’s award he said in his best baritone goes to the film Shahid. While the hall filled with applause he called the Director Hansal Mehta and the protagonist Ram Kumar Yadav to the stage.

Tears welled up in many eyes because Shahid is the real life story of Shahid Azmi the young human rights lawyer who was gunned down in 2010 for defending a 26/11 accused, who as it turns out was acquitted in 2011. Hansal, like Abbas could not find a financier who would back a film with no commercial value. It was his family which helped and thus the film saw light of the day. Abbas would have made a ‘Shahid’ had he lived today, Amitabh said in a voice which thrilled and lifted the crowd. ‘Socially relevant films will continue to be made and people will aspire to make films which will win this prestigious Abbas award instituted by the Guild’.

As Amitabh ended the segment with a few lines of a poem dedicated to Abbas who he called a Farishta (angel) the stage darkened. Outside it was a full moon night and the moon above the sea at Worli was brilliant beyond description. A Farishta had indeed inspired the sky’s brightest lamp to burn brighter that night.