THE MESSAGE

Book Extract

The message is clear: Indians will not submit to another Partition. Citizens of a multi-religious, multicultural nation, they are refusing to be partitioned into Hindus and Others and have made it known by their countrywide resistance to the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) and related measures which target Muslims as outsiders. The rejection of a citizenship law based on religious identity has triggered an uprising like no other since the fight for freedom.

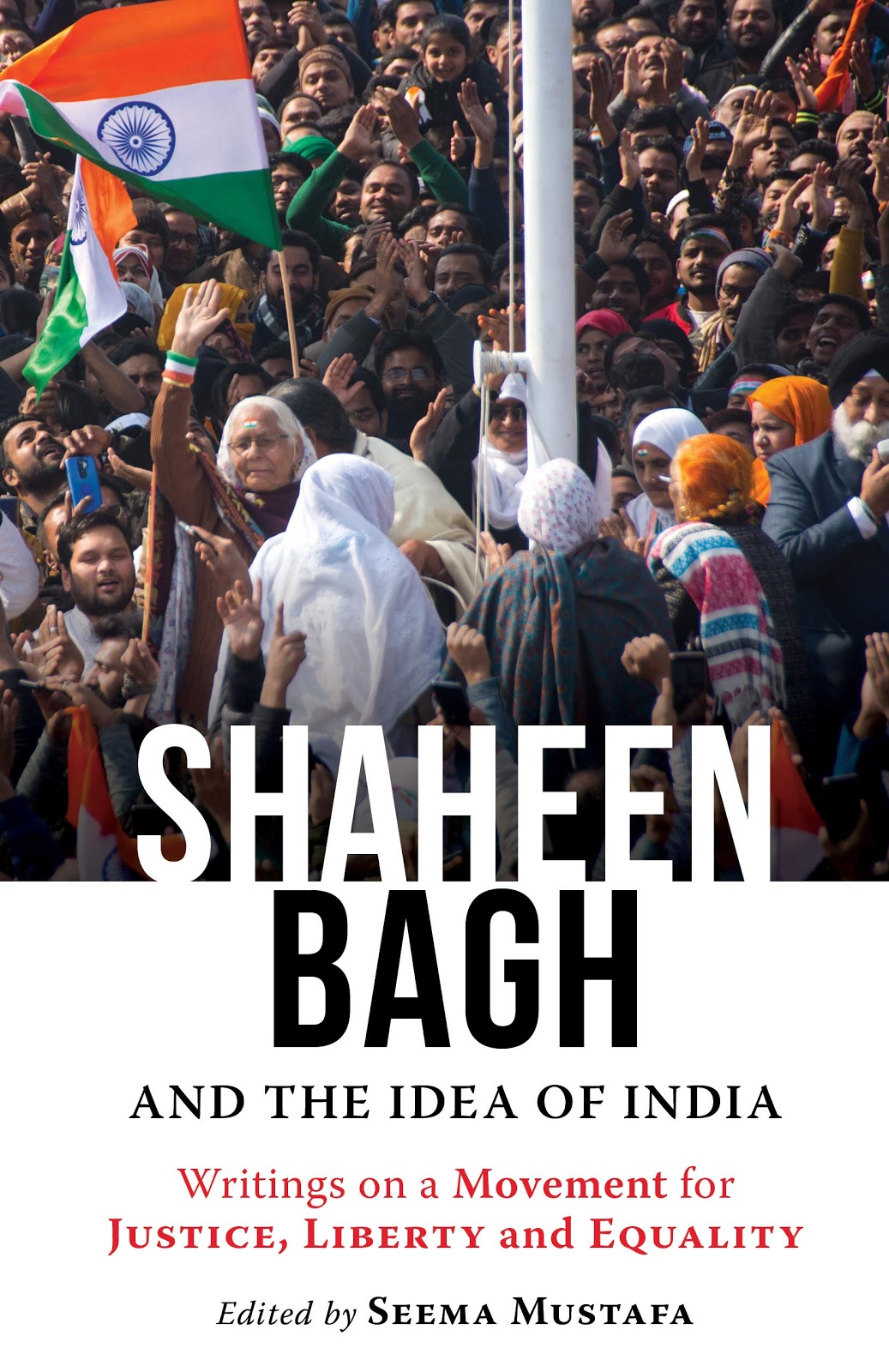

Protests began after the Act was passed in Parliament and students at Jamia Millia Islamia, Jawaharlal Nehru University and Aligarh Muslim University were attacked for opposing it. Reacting to the brutality, a group of women started a peaceful sit-in at Shaheen Bagh on 15 December 2019, proclaiming the right of all Indians to Indian citizenship, and within days their number had grown to the hundreds, then thousands. Men and women of communities not affected by CAA made common cause with them. The sit-in burst its bounds and became a phenomenon crossing frontiers and differences, just as the national movement for independence under Mahatma Gandhi had done.

But the extraordinary features this time are that this is a women’s movement, mainly Muslim, leaderless and spontaneously sprung. Something new has happened. Ordinary women of no political background or experience have brought politics down from the distant heights of power to the street, where the issue in question cannot be ignored.

The young, old and the very old who sat through bitterly cold days and nights for over three months in a massive satyagraha included working women and university students, but mainly housewives who had never stepped out of their homes unaccompanied, some with children who could not be left alone at home. There may have been some among them who crossed frontiers of their own by stepping out and demonstrating by their presence that there was no going back to submission under patriarchy or any unjust law or any unequal book of rules.

It is not the first time Indian women have claimed THE public/political space. The anti-CAA movement continues a great tradition, and makes it greater. In 1930, Gandhi broke the British government’s Salt Law and its ownership of India’s salt by walking from his Sabarmati Ashram to the seaside at Dandi to manufacture salt. His example was widely followed. In Bombay a group of women went to Chowpatty on the day that Gandhi picked up a handful of salt at Dandi.

They were led by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya and joined by housewives carrying clay and brass pots and pans, and ‘chulhas’ to make salt. Later they sold it outside the Bombay Stock Exchange and the High Court. An interview records that Kamaladevi walked into the court and asked the magistrate to buy ‘the salt of freedom’. Salt—a necessary ingredient of food associated with every kitchen—had become a symbol of revolt that brought women from the domestic to the public space.

Sarojini Naidu, the first Indian woman to become president of the Indian National Congress, led the second march to the government-owned Dharasana Salt Works, a site where unarmed marchers pledged to non-violence had been savagely attacked by armed police, leaving battered and bloodied bodies on the sand. Sarojini Naidu figures in the stone sculpture of the Salt March in Delhi, along with another woman, Matangini Hazra, who came from a village in Bengal, and was shot dead some years later by a British police officer during the Quit India movement of 1942.

There was no going back after 1930. Women came out into the streets to join civil disobedience in ever larger numbers, marking the beginning of their participation as a force in politics. They picketed foreign cloth and liquor shops, organised boycotts of British goods and took out ‘prabhat pheris’, early-morning processions. Recalling those times, the British Quaker Horace Alexander remembered: ‘Day by day

the streets of Bombay would be livened in the early morning with their songs of freedom...Women could be found all over the city...Many of them had never taken part in public life before.’ In the streets they faced brutal lathi charges and a record number of them were imprisoned during the civil disobedience campaign in 1932. Leaders among them, including Satyavati Devi (Swami Shraddhanand’s daughter) and Perin Captain (Dadabhai Naoroji’s granddaughter), not content with picketing and boycott, demanded and seized a greater role in the rebellion.

In 1932, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit presided over a crowded public meeting in Allahabad where the independence pledge was taken. She was arrested and sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment, the first of her three imprisonments under British rule.

The enlightened democracy that these brave activists fought for is in peril. Divide and rule is now policy. The slaughter of Muslims goes unpunished. Democratic institutions are under ferocious attack. In effect, we live in a police state where those who disagree with the ruling dispensation do not have recourse to justice. Not surprising, then, that huge numbers assembled at Shaheen Bagh and cried ‘Enough is enough’, or that civilised voices across the country have supported them. At a time when our constitutional rights face extinction, the tradition of Indian women in politics has taken a spectacular stride forward in their defence.

Shaheen Bagh and the Idea of India

Edited by Seema Mustafa

Pubishers Speaking Tiger