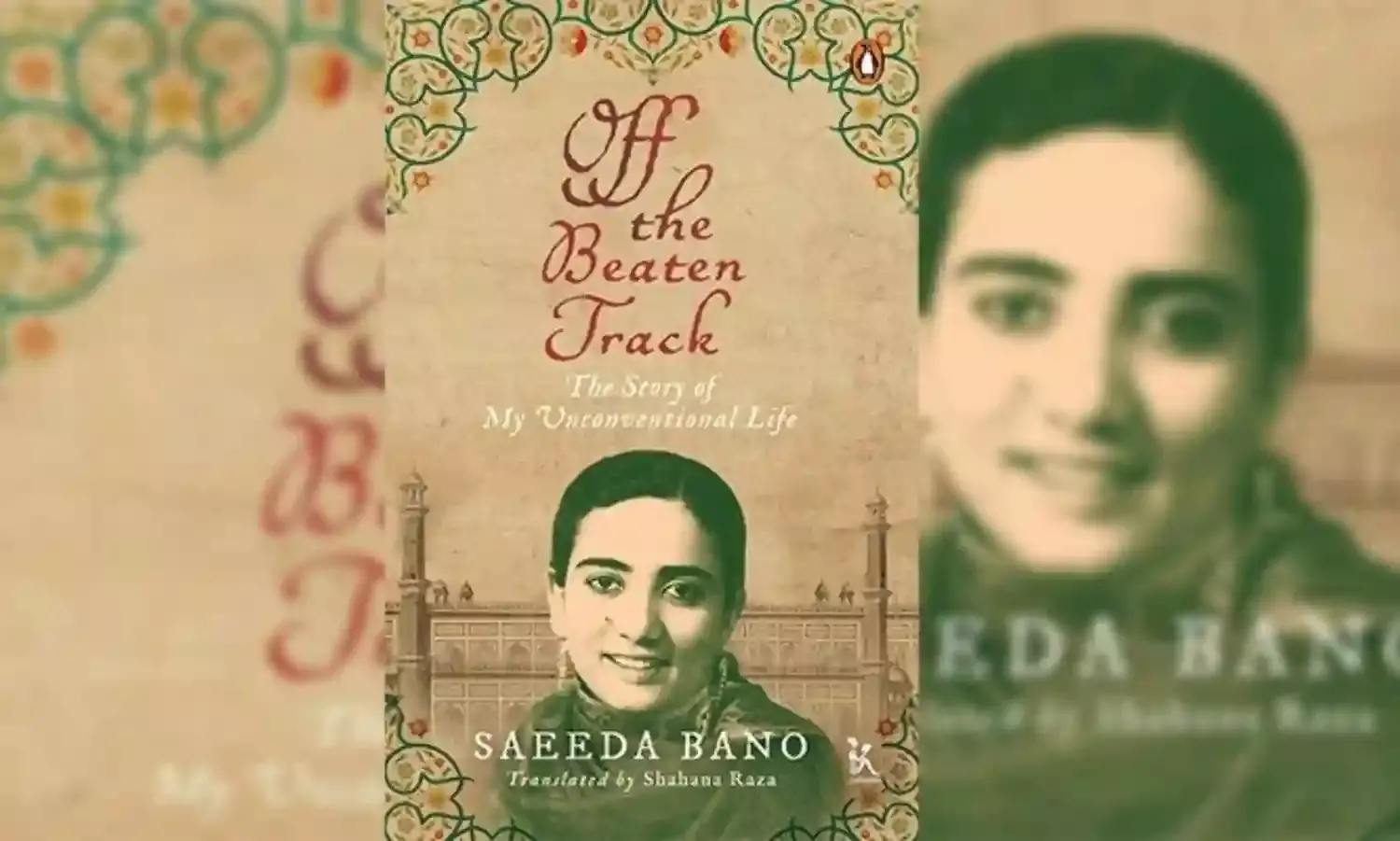

The Inimitable Saeeda Bano Lived Her Life Off The Beaten Track

Book review

Off the Beaten Track is the last hurrah of Saeeda Bano who managed to live life on her own terms even in the midst of rampant male narcissism.

The inimitable Saeeda Bano was the first female news reader at All India Radio (AIR) since 1947. She was affectionately called Bibi.

Born in 1913 in Bhopal, Bibi blames Lucknow for some of the woes she was forced to face in life. The suffocation that women felt in Lucknow then was due to deep rooted conservative values that were followed blindly unlike her life in Bhopal.

Bhopal in early 20th century, was ruled by Nawab Sultan Jahan Begum. The unexpected result of having a woman as head of state was enough to improve the status of the fairer sex within that society.

In this ancient world of ours it is rarely, if ever, that a woman gets the chance to hold the reins of power in her hands. Which is why Nawab Sultan Jahan Begum’s entire concern, during her tenure as monarch was to make Bhopal a progressive nation. She wanted to introduce and implement dynamic strategies to make the lives of her subjects content and comfortable. She was also extremely focussed and keen to get women out of the dark confines of ignorance and launched several schools for girls and compelled orthodox families to enroll their daughter so they could receive a proper education despite opposition from those fundamentally against the idea of female education.

Barely in her teens, Saeeda was admitted in 1925 to the Karamat Hussain Muslim Girls High School in Lucknow as a boarder. Her broadminded father was keen that she get a good formal education and study as far as it is was possible for a girl back then.

Saeeda graduated from Lucknow’s prestigious Isabella Thoburn College. In school she was less interested in academics and more at the idea of seeing a new world, and playing sports.

The book is filled with descriptions of Lucknow, a city that was epi center of a dying but once a high oriental culture. Lucknow was also the hub of the freedom struggle in pre independent India.

The social milieu in Lucknow during Lord Harcourt Butler’s time had reached rock bottom. Men and women in this decadent world were speeding towards impending disaster competely clueless that behind the seductive glamour and rosy charm of this aristocratic society lay nothing but doom. This was one aspect of Lucknow society.

The other reality, continues Bibi was the large presence of the British East India Company officials in Lucknow. This influenced the residents of the city increasingly who were introduced to western culture and thought. The city tried to emulate the fastidiousness of the English for cleanliness, punctuality, order, discipline and the immense importance paid to education.

Slowly the western way of life began to spread its liberal roots within the orthodox society of Lucknow.

But Bibi was loathe to leave the cherished childhood world of Bhopal. Having to live permanently in Lucknow where she was married by her elders at the age of 19 years, she felt a strange sense of suffocation in the very air she breathed.

She complains of having to constantly behave in an exemplary manner. She recalls how totally clueless she was about the biological needs of a husband. And also of her own outspoken and mischievous nature. When she wanted to cry she was told to smile. That made her feel even more miserable.

In her day to day behaviour she was demure and respectful but everyday the mother of two, mourned the death of the playful girl in her who could chatter nonsensically, laugh uncontrollably for no apparent reason and indulge in silly antics with friends. Shackled with endless precautions made her breathless. She quotes Ghalib to express her state of mind:

phir waz-e-ahteyaat se ghutne laga hai dum

Fingers were constantly pointed at her for this and for that. People frowned at her for befriending Akhtari Bai, a courtesan. Bibi was present at the wedding of Akhtari to Ishtiq Ahmed Abbasi, leading Lucknow lawyer, a marriage that transformed the social status of the ghazal queen from Bai to Begum. Bibi was rebuked for opening her home to Jamila whose husband was a Hindu.

When she found it impossible to go on living in Lucknow, she left the sleepy city, so laid back and with an intoxicating air of complacency. She moved to Delhi to work as a news reader at AIR. Prior to this no woman had been employed by either the BBC or AIR to read the news.

She found a room to stay at the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) in Delhi, a city where she knew no one. She was oblivious of the fallout of the birth of Pakistan that same year. Unaware of the impending catastrophe about to engulf the Indian subcontinent, Bibi arrived in Delhi in August.

After the independence day celebrations on 15 August, 1947 incidents of communal violence rapidly intensified across different localities in Delhi.

When I arrived in Delhi barely a month back I could not have imagined even in my wildest dreams what would happen here…I had managed to walk out of a conservative environment thanks to my bold and courageous nature but that world at the end of the day was extremely safe.

She had absolutely no clue that Partition would turn into such a violent and ghastly event. She was forced to take refuge along with hundreds of other people in the home of Rafi Ahmad Kidwai, India’s Agriculture Minister. Today that house on Maulana Azad Marg is where India’s Vice-President lives.

Here Bibi saw history unfold before her eyes. She saw activist and politician Mridula Sarabai running in to see Kidwai.

She heard Congress leader Madan Mohan Malviya consulting with Kidwai while Feroz Gandhi, the journalist and politician son in law of Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first Prime Minister listened. Everyone was sick with concern over the killing of human beings on streets.

She watched Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman getting out of Jamal Mian of Firangi Mahal’s car. She refutes the rumour that Khaliquzzamaan, a top Muslim League leader had fled India in a burkha and says that he left for Pakistan from the home of Rafi Ahmad Kidwai in front of her eyes.

In 1948 Bibi visited Birla House to listen to Gandhi speak in person. She heard Gandhi address a gathering. The father of the Nation had tried to comfort the masses suffering due to Partition. He tried to reinforce feelings of humanity amongst them.

When he started to speak his words were steeped in sadness. I felt there was a sense of defeat, of failure in the soft tone of his voice.

A few days later, on January 30 Gandhi was murdered. That evening Bibi was scheduled to deliver the 6 pm news bulletin. The news room was attached to Birla House and from here Gandhi Ji’s sermons were broadcast live. When gunshots were heard at the Birla House Melville De Mellow, a senior English news reader exclaimed that someone had shot Gandhi Ji.

Bibi felt she could not read the news. She was crying copiously. A considerate news director got someone else to read the news on air that sad evening.

Gandhi’s death had an extremely disturbing impact on the Muslim community. There was fear that riots against Muslims might begin afresh.

Now, so many years after independence, the only way to save ourselves from witnessing the destructive results of the seeds of hatred we have sown, is to not let these feelings grow roots.

Bibi goes on to say that once life settled down, her mornings, afternoons and nights in Delhi were spent juggling between shifts at the Radio Station.

But her spare time was spent in romancing.

In the 1970s when she was almost 60 years old, Bibi married a man she had already known for over two decades.

There is much in the book that some of us already know. For Bibi would talk a lot about herself before her death in 2001. And each time she suspected that her story might be giving us younger people ideas, she had looked anxious almost fearful. Waving an index finger she would chide, “Don’t you dare do what I did!”

But Bibi’s advise always came a little too late. For she had already lit the torch of endless possibilities that life offers even women. That torch is now blazing bright for all to see countless lanes and by lanes to choose from. For Bibi’s story teaches us that none of us must follow the beaten track if we don’t want to. In the end the choice is clearly ours.

Off the Beaten Track, originally in Urdu is translated by Shahana Raza, published by Penguin Random House and co-published by Zubaan, 2020.